Announcement |

The Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) is pleased to announce the nine recipients of its 2020 fellowship awards. Introduced in 2017, CIPESA’s fellowship programme aims to increase the quality, diversity and regularity of research and media reporting on ICT, democracy, and human rights in Sub-Saharan Africa.

The fellowship programme cultivates links between the academic community and practitioners in the ICT field for mutual research, learning, and knowledge exchange, so as to create the next generation of ICT for democracy and ICT for human rights champions and researchers.

In the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, the nine fellows will primarily focus their energies on researching Covid-19 related censorship and surveillance practices and policy/regulatory responses by governments and private actors; and documenting trends and developments in technology for public good policy and practice.

Meet the fellows:

Astou Diouf – Senegal – Astou is a lawyer with undergraduate and postgraduate qualifications from Faculté des Sciences Juridiques et Politiques (FSJP), l’Université Cheik Anta DIOP de Dakar, with extensive experience in business litigation, cybercrime, and cybersecurity. She will research the role of internet intermediaries and service providers in the fight against Covid-19 in Senegal, including on issues such as facilitating increased access to the internet, privacy and personal data infringements, and content regulation.

Astou Diouf – Senegal – Astou is a lawyer with undergraduate and postgraduate qualifications from Faculté des Sciences Juridiques et Politiques (FSJP), l’Université Cheik Anta DIOP de Dakar, with extensive experience in business litigation, cybercrime, and cybersecurity. She will research the role of internet intermediaries and service providers in the fight against Covid-19 in Senegal, including on issues such as facilitating increased access to the internet, privacy and personal data infringements, and content regulation.

Hopeton S. Dunn, PhD – Botswana – Hopeton is a Professor of Media and Communications at University of Botswana. He is also a non-resident Senior Research Associate at the School of Communication, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. He is the former Director of the Caribbean School of Media and Communication (CARIMAC), University of the West Indies (UWI), Jamaica, where he also headed the Mona ICT Policy Centre (MICT). He is interested in communications policy reform, digital literacy and inclusion, effective internet access and equity, especially as they relate to people in the Global South. His work spans media regulation, technology policy-making, and new theoretical constructs for development.

Hopeton S. Dunn, PhD – Botswana – Hopeton is a Professor of Media and Communications at University of Botswana. He is also a non-resident Senior Research Associate at the School of Communication, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. He is the former Director of the Caribbean School of Media and Communication (CARIMAC), University of the West Indies (UWI), Jamaica, where he also headed the Mona ICT Policy Centre (MICT). He is interested in communications policy reform, digital literacy and inclusion, effective internet access and equity, especially as they relate to people in the Global South. His work spans media regulation, technology policy-making, and new theoretical constructs for development.

With a focus on Botswana and South Africa, Prof. Dunn will study the status of broadcast and online media regulation; technology and learning during the Covid-19 pandemic; and internet access and inclusion.

Afi Edoh – Togo – Togolese technology enthusiast Afi will study digital transformation and the digital economy in Ivory Coast, Ghana, and Togo during the Covid-19 pandemic, to determine value and innovation opportunities as well as challenges. She is a member of the organising committee of the Internet Governance Forum for Youth in West Africa and has also served on the United Nations Internet Governance Multi-Stakeholder Advisory Group (MAG). She holds a Masters and Bachelors in Information Technology from Sikkim Manipal University.

Afi Edoh – Togo – Togolese technology enthusiast Afi will study digital transformation and the digital economy in Ivory Coast, Ghana, and Togo during the Covid-19 pandemic, to determine value and innovation opportunities as well as challenges. She is a member of the organising committee of the Internet Governance Forum for Youth in West Africa and has also served on the United Nations Internet Governance Multi-Stakeholder Advisory Group (MAG). She holds a Masters and Bachelors in Information Technology from Sikkim Manipal University.

Mohamed Farahat – Egypt – Mohamed is an Egyptian human rights lawyer, specialised in refugees and migration. He is a member of the Steering Committee of Internet Rights and Principles Coalition (IRPC), a member of the Multi-Stakeholder Advisory Group (MAG) of the North Africa Internet Governance Forum, and the National Coordinator of the African Civil Society on Information Society (ACSIS) Egypt chapter. Since 2014, he has worked with the Egyptian Foundation for Refugees Rights (EFRR). He holds a degree in Law from Cairo University, and post-graduate diplomas in International Negotiation; Human Rights and Civil Society; African Studies; and International Law. Currently, he is a Master Degree researcher in the Faculty of African Studies – Cairo University.

Mohamed Farahat – Egypt – Mohamed is an Egyptian human rights lawyer, specialised in refugees and migration. He is a member of the Steering Committee of Internet Rights and Principles Coalition (IRPC), a member of the Multi-Stakeholder Advisory Group (MAG) of the North Africa Internet Governance Forum, and the National Coordinator of the African Civil Society on Information Society (ACSIS) Egypt chapter. Since 2014, he has worked with the Egyptian Foundation for Refugees Rights (EFRR). He holds a degree in Law from Cairo University, and post-graduate diplomas in International Negotiation; Human Rights and Civil Society; African Studies; and International Law. Currently, he is a Master Degree researcher in the Faculty of African Studies – Cairo University.

As part of the fellowship, Mohamed will document inclusion of refugees in the technology-based responses to the Covid-19 pandemic in Egypt; and the role of the judiciary in the internet freedom landscape in North Africa.

Tusi Fokane – South Africa – Tusi, the former Executive Director of the Freedom of Expression Institute (FXI), will study the availability and use of digital technologies to combat the spread of Covid-19 in South Africa, with a focus on the criminalisation of misinformation, and obligations on service providers to remove fake news from their platforms. Furthermore, she will study the country’s readiness for electronic voting to comply with social distancing and other movement restrictions during the upcoming local government elections. Tusi is a co-founder and member of the Steering Committee of Re-Create, a coalition of South African creators who advocate for fair and balanced provisions in the ongoing copyright amendment process. She holds a Masters in Management degree in Public Policy from Wits University. Her particular interests are freedom of expression, technology, and human rights.

Tusi Fokane – South Africa – Tusi, the former Executive Director of the Freedom of Expression Institute (FXI), will study the availability and use of digital technologies to combat the spread of Covid-19 in South Africa, with a focus on the criminalisation of misinformation, and obligations on service providers to remove fake news from their platforms. Furthermore, she will study the country’s readiness for electronic voting to comply with social distancing and other movement restrictions during the upcoming local government elections. Tusi is a co-founder and member of the Steering Committee of Re-Create, a coalition of South African creators who advocate for fair and balanced provisions in the ongoing copyright amendment process. She holds a Masters in Management degree in Public Policy from Wits University. Her particular interests are freedom of expression, technology, and human rights.

Jimmy Kainja – Malawi – Jimmy Kainja is a lecturer in media, communication, and cultural studies at University of Malawi, Chancellor College. His main areas of academic and research interest are communication policy and regulation, journalism, new media, (mis)information and disinformation, freedom of expression, and the intersection between media and democracy. Kainja has been a blogger since 2007 and is a founding member of Africa Blogging, which he co-edited between 2015 and 2019. In addition, Kainja has written for a number of reputable international media organisations including the BBC, The Guardian, Aljazeera, and New African. Locally he is a regular contributor of analytical articles to Nation Publications Limited newspapers.

Jimmy Kainja – Malawi – Jimmy Kainja is a lecturer in media, communication, and cultural studies at University of Malawi, Chancellor College. His main areas of academic and research interest are communication policy and regulation, journalism, new media, (mis)information and disinformation, freedom of expression, and the intersection between media and democracy. Kainja has been a blogger since 2007 and is a founding member of Africa Blogging, which he co-edited between 2015 and 2019. In addition, Kainja has written for a number of reputable international media organisations including the BBC, The Guardian, Aljazeera, and New African. Locally he is a regular contributor of analytical articles to Nation Publications Limited newspapers.

In the context of the February 3, 2020 Constitutional Court nullification of the presidential elections and scheduled fresh polls in June 2020, and in parallel to the Covid-19 pandemic, Kainja will study hate speech and misinformation, data protection, and access to information.

Jean Paul Nkurunziza – Burundi – Jean Paul, a psychology and education sciences graduate of the University of Burundi, has been involved in digital rights policy and internet governance with the DiploFoundation and Internet Society since 2007. In 2010, he was awarded a fellowship at the United Nations Internet Governance Forum Secretariat. His CIPESA fellowship will focus on the political tensions in Burundi, including the recent internet disruption during elections; and ICT sector reforms by the new government, related to cybersecurity, privacy, and data protection.

Jean Paul Nkurunziza – Burundi – Jean Paul, a psychology and education sciences graduate of the University of Burundi, has been involved in digital rights policy and internet governance with the DiploFoundation and Internet Society since 2007. In 2010, he was awarded a fellowship at the United Nations Internet Governance Forum Secretariat. His CIPESA fellowship will focus on the political tensions in Burundi, including the recent internet disruption during elections; and ICT sector reforms by the new government, related to cybersecurity, privacy, and data protection.

Dunia Tegegn – Ethiopia – Dunia is a legal consultant, who has previously worked as an Almami Cyllah Fellow with Amnesty International (United States) and as a Human Rights Officer at the East Africa Regional Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. Dunia also worked as a Program Officer on Ending Violence against Women and Girls at UN Women Ethiopia, and on child protection issues with UNICEF Ethiopia. She holds a Master of Laws in National Security from Georgetown University Law Center and a Master of Arts in Human Rights from Addis Ababa University. Dunia is the first Africa Fellow for Georgetown’s LAWA program to earn a Master of Laws in National Security. She earned her bachelor degree in law from Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia. Dunia is a member of the Pan African Lawyers Union (PALU), the Ethiopian Bar Association, and the Ethiopian American Bar Association.

Dunia Tegegn – Ethiopia – Dunia is a legal consultant, who has previously worked as an Almami Cyllah Fellow with Amnesty International (United States) and as a Human Rights Officer at the East Africa Regional Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. Dunia also worked as a Program Officer on Ending Violence against Women and Girls at UN Women Ethiopia, and on child protection issues with UNICEF Ethiopia. She holds a Master of Laws in National Security from Georgetown University Law Center and a Master of Arts in Human Rights from Addis Ababa University. Dunia is the first Africa Fellow for Georgetown’s LAWA program to earn a Master of Laws in National Security. She earned her bachelor degree in law from Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia. Dunia is a member of the Pan African Lawyers Union (PALU), the Ethiopian Bar Association, and the Ethiopian American Bar Association.

For her fellowship, she will study the role of the internet and access to information during 2020 elections in Egypt, Ethiopia, and Somalia.

Melissa Zisengwe – South Africa – Melissa is a Program Project Officer with the Civic Tech Innovation Network at Wits Governance School, based in South Africa. She holds an honours degree in Journalism and Media Studies and a Bachelor of Arts in English Language and Linguistics and Journalism and Media Studies from Rhodes University. Her work at the Civic Tech Innovation Network and Jamlab (also at Wits) focuses on digital innovation in Africa, including digital journalism and media, and promoting the growth and development of appropriate and effective uses of digital technologies in connecting government and citizens, in public participation, in transparency and accountability, and in delivering public services. In 2019 she was part of the Index on Censorship Youth Advisory Board – a project by Index on Censorship aimed at engaging with young people aged 16-25 from around the world and gathering their views on freedom of expression issues.

Melissa Zisengwe – South Africa – Melissa is a Program Project Officer with the Civic Tech Innovation Network at Wits Governance School, based in South Africa. She holds an honours degree in Journalism and Media Studies and a Bachelor of Arts in English Language and Linguistics and Journalism and Media Studies from Rhodes University. Her work at the Civic Tech Innovation Network and Jamlab (also at Wits) focuses on digital innovation in Africa, including digital journalism and media, and promoting the growth and development of appropriate and effective uses of digital technologies in connecting government and citizens, in public participation, in transparency and accountability, and in delivering public services. In 2019 she was part of the Index on Censorship Youth Advisory Board – a project by Index on Censorship aimed at engaging with young people aged 16-25 from around the world and gathering their views on freedom of expression issues.

Inspired by the African Civic Tech database and the South Africa Cities Network Call for Local Covid-19 Data Responses, which is compiling an open evidence mapping of the use of open government data to address the Covid-19 response in South Africa’s cities and provinces, Melissa will study the use and adoption of civic tech during Covid-19 in select African countries. The research will pay close attention to Covid-19 civic tech and data responses related (but not limited to): Epidemiological info — a disease spread maps, statistics, dashboards; Disaster response information; Health and risk information; Services — food relief, disruptions, etc.; Information, guidelines, resource tools — for businesses, communities, citizens; Research and advocacy; and Enhancing public communication and engagement and action.

Look out for the fellows’ outputs including blogs, policy briefs, and research reports on CIPESA’s online platforms in the coming months.

Countering Nonconsensual Sharing of Intimate Images: How far do Uganda’s Laws Go?

By African Feminism |

In 2014, when Uganda introduced a law against pornography, few anticipated that it would largely be used to target and prosecute women, and specifically women whose intimate photos have been shared online without their consent. The Anti-Pornography Act, whose enforcement is spearheaded by a 9-member Pornography Control Committee is mandated to “apprehend and prosecute perpetrators of pornography, collect and destroy any pornographic materials and detect the sharing of nude materials on computers, phones and television.”

Pornography, according to the Act is “any representation through publication, exhibition, cinematography, indecent show, information technology or by whatever means, of a person engaged in real or stimulated explicit sexual activities or any representation of the sexual parts of a person for primarily sexual excitement.” The Act makes it a crime to produce, traffic in, publish, broadcast, import, export, sell or abet any form of pornography, and anyone found guilty of the offence faces a 10-year jail term.

It is on these grounds that over the years in Uganda, particularly women whose private images have been leaked on the internet without their consent have been arrested by police and tasked to explain how their photos ended up on the internet.

In 2018, a university student was arrested, charged in court and sent to prison for allegedly producing and broadcasting a pornographic video contrary to section 13(1) and (2) of the Anti-Pornography law.

In another famous case, Desire Luzinda, a renowned artiste was forced to make a public apology after the Minister of Ethics and Integrity issued threats to arrest her for engaging in pornography following leakage of her intimate photos on social media by an ex-boyfriend.

The sharing of private nude images, often by jilted lovers and hackers is used as a tool to shame women, blackmail them or extort money from them. Lindsey Kukunda, who runs the online platform Not Your Body, says it is worrying that the law focuses on punishing victims whose images have been leaked rather than the perpetrators of the crime.

“When it comes to non-consensual sharing of intimate images, the law has manipulated the situation so that women can be punished for being women. They don’t try to look for the men. It is always the women that they target,” Kukunda says.

She adds that in many of the documented cases, the photos are leaked to blackmail or extort money from the victims and had nothing to do with pornography. “The aim is often to cause distress and pain to the victims but the police make no effort to look for the blackmailer. It is easier for them to go for the woman than to carry out investigations and find the culprits who have leaked the images,” she adds.

With a focus on victims and many perpetrators getting away with their actions, this specific kind of online violence against women has been a growing trend in Uganda.

Gendered Impact Of The Anti-Pornography Law

A recently released research study by the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA), looked at online safety for women. The findings show that despite having a lesser presence on the internet, more women are likely to face various forms of online violence compared to their male counterparts, further undermining their participation in online spaces.

Figures from the Uganda Communications Commission (UCC) show that internet penetration currently stands at 38 per cent among the general population. In another study, the Web Foundation found that only 21 per cent of women compared to 61 per cent of men had accessed the internet in the six months prior to conducting the survey. Education and income levels played an important factor in women’s internet access, where women with some secondary school education are six times more likely to be online than those with primary and no education.

The CIPESA study under the Women At Web project involved interviews with university students, journalists, bloggers, activists, human rights defenders and business owners.

“The absence of laws designed to specifically address the various forms of digital violence such as ‘revenge pornography’, trolling and threats, and the lack of sufficient in-country reporting mechanisms exacerbate these challenges and often result in many women being forced to go offline or resorting to self-censorship,” the study reveals.

Ophelia Kemigisha, a human rights lawyer at Chapter Four Uganda, says what enforcers of the anti-pornography law are doing is simply policing women’s bodies. She says that the violence often meted against women online, as it is offline, has not been taken seriously. Instead, like violence offline, it is usually depicted as a simple misunderstanding between two parties.

“Unless we start to see non-consensual sharing of images of women as violence, we shall continue to see women victims being targeted instead of the perpetrators.”

The vagueness of the law further complicates its implementation. Recourse for Ugandan women, according to Kemigisha could be in the Sexual Offences Bill 2019, which is currently before Parliament. In the proposed law, it would be criminal for a person to send or transmit materials of a sexual nature, with violations attracting a fine or prison term of seven years or both.

By making it a sexual offence, victims would also be able to anonymously report cases without fear of being identified, something that is not possible under the current laws. Legislator Anna Adeke agrees. Cyber violence, she says, has a big gender aspect to it and so the laws must be sensitive as regards to gender because we all suffer differently on cyber platforms.

“Knowing that the media which occupies most of the cyberspace is a very patriarchal arm, it’s important that laws are gender appropriate so that we make it increasingly risky for people to abuse women online,” says Adeke.

Peace Oliver Amuge, from Women of Uganda Network (WOUGNET), an organisation that supports women’s use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) says based on years of research on technology-related violence against women, for victims, one of the biggest challenges is the mechanism of where to report cases as the Police is often not competent enough to deal with cases.

Jimmy Haguma, the head of cybercrimes unit at the Uganda Police acknowledges that law enforcement officers are not well trained at investigating cases of digital crimes, especially those involving non-consensual sharing of private images.

“One of our biggest challenges in addressing online violence against women is where they can report cases to. The typical police station is not equipped with that. We are trying to devise online methods where people can report cases.”

Apprehending perpetrators, according to Haguma, has also been complicated by the fact cyber-related crimes against women, including the non-consensual sharing of their images, are often carried out by people using stolen phones.

“They use stolen phones to send text messages to their victims to send money through mobile money so that they don’t publish their images. If a person doesn’t make a call, then tracking such a person then becomes difficult,” he said.

New Initiatives Closing The Response Gaps

Without adequate avenues for victims to report cases, innovative platforms such as the Women At Web Portal that is currently under development hopes to fill the void and make it easy for women victims to report cases of violations online and safely. The portal is being spearheaded under the Women at Web project, an alliance of five organisations, including Chapter Four Uganda, the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA), the Defenders Protection Initiative (DPI), Not Your Body and Unwanted Witness. The alliance is working to improve digital literacy and security among African women in Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda and Uganda.

Brian Byaruhanga from the Defenders Protection Initiative, which is spearheading the development of the portal says the intention is to be able to acquire evidence based on the violations that women are experiencing online, and also make it easy for victims to report cases anonymously and safely.

“The portal will help us in policy advocacy and improve the protection of women online. As it stands now, there is no proper documentation of these cases and yet for advocacy, you need the data,” says Byaruhanga.

The portal will also be used to generate information on the types of violations, where and how they are happening and which categories of women are most targeted. This data, according to Byaruhanga will subsequently be shared with law enforcement agencies such as the Police, to ease their investigations and therefore help victims hold perpetrators to account.

Kukunda from Not Your Body says women need to take lead in challenging social conventions for their own sake. “ Women have to rise above the illusion that being sexual is a sign of immorality. It is one of the reasons they feel ashamed to report even to their friends,” adding that public conversations about these issues is what will help improve awareness and acceptance of women as sexual beings not to be demonised for it.

Support is also paramount. While there are organisations that offer free legal advice to those who cannot afford lawyers, Kukunda says women need to take the initiative to study laws such as the Data Protection Act so they can take action into their own hands.

“Women should never go alone to report a case to a police station or be naive about the system. The system is not ready to help women, nor is it interested,” Kukunda adds.

In Malawi and Uganda, non-consensual sharing of private images has yet to be widely recognized and/or acknowledged as a gendered issue. Consequently, it remains below the radar of most activists and prominent gender advocates. Globally, however, there is growing recognition that digital technology such as email, the social media platforms and mobile phone technologies are being used as a tool to harass, intimidate, humiliate, coerce and blackmail.

This article was first published by the African Feminism on June 18, 2020.

Coalition of Civil Society Groups Launches Tool to Track Responses to Disinformation in Sub Saharan Africa

Press Release |

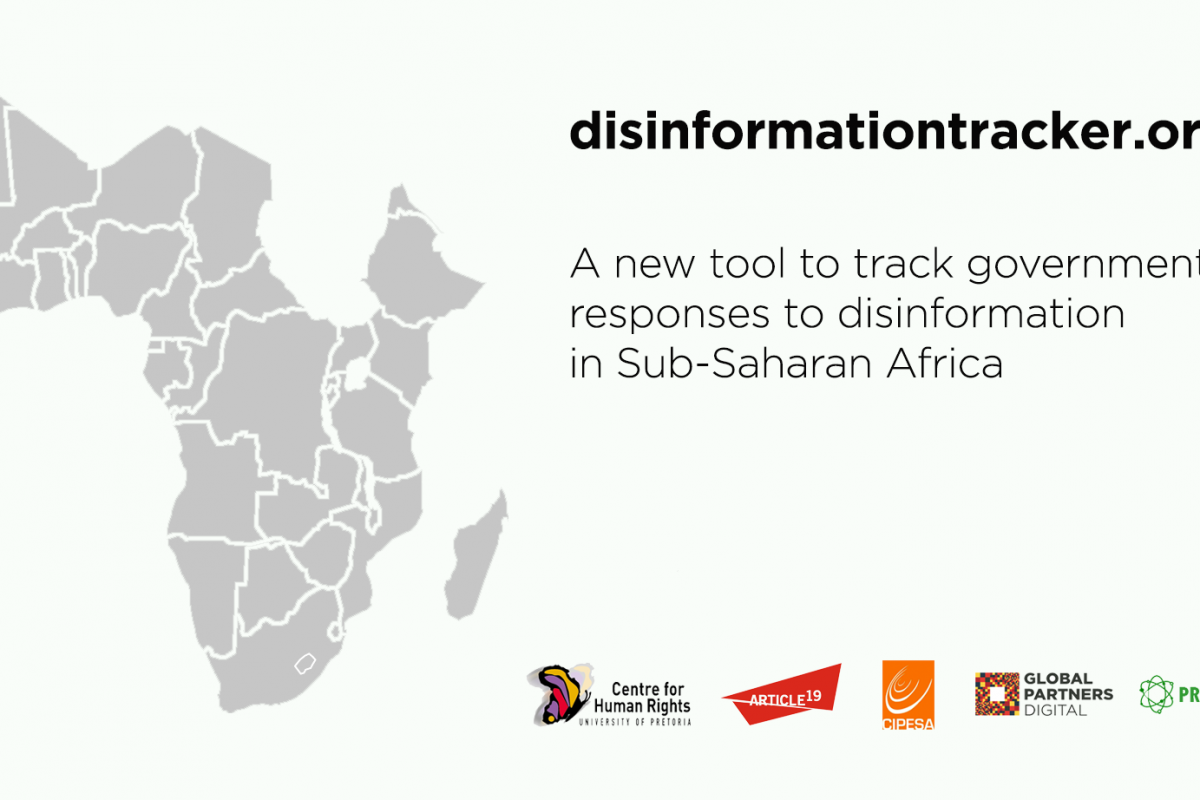

Today, Global Partners Digital (GPD), ARTICLE 19, the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA), PROTEGE QV and the Centre for Human Rights of the University of Pretoria jointly launched an interactive map to track and analyse disinformation laws, policies and patterns of enforcement across Sub-Saharan Africa.

The map offers a birds-eye view of trends in state responses to disinformation across the region, as well as in-depth analysis of the state of play in individual countries, using a bespoke framework to assess whether laws, policies and other state responses are human rights-respecting.

Developed against a backdrop of rapidly accelerating state action on COVID-19 related disinformation, the map is an open, iterative product. At the time of launch, it covers 31 countries (see below for the full list), with an aim to expand this in the coming months. All data, analysis and insight on the map has been generated by groups and actors based in Africa.

Countries currently covered by the map: Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Rwanda, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

For further details, contact [email protected]

Quotes from groups:

Commenting on the launch, Article19 said: “Disinformation constitutes a major threat to the freedom of expression and the right to access information and it is geared to mislead the population and influence their opinions and views. The fight against disinformation requires a multifaceted approach ranging from education, awareness raising, proactive disclosure of public interest information, fact checking; independent regulation and effective self-regulation by legacy media and social media platforms among others. With the COVID19 pandemic, it is more important than ever that collective efforts are made to curb the impact of disinformation on public health and the rights of the public to know.”

“National legislation and policies aimed at countering and responding to disinformation should always strike the right balance between the need to protect people against this practice and the respect of human rights especially freedom of expression. Such measures should not be used to interfere or block divergent opinions and dissident voices. We are pleased to have been part of this joint initiative that has enabled us to work together with sister organisations in and outside the continent to publish this disinformation tracker.

This tracker is a start-up that will usher in more in-depth work analysing laws and policies around the disinformation phenomenon in the region, engaging media and civil society in analysis-based advocacy geared towards governments and intermediaries to protect human rights—particularly freedom of expression—in their disinformation response, to ensure any restriction and penalty are always justifiable, proportionate and compliant with international standards.”

The Centre for Human Rights said: “Disinformation is a global phenomenon whose effects are felt across the political, economic and social spectrum. Efforts being undertaken to counter the scourge of disinformation should respect human rights, especially freedom of expression. In addition, a sustained approach is required and should involve different stakeholders employing legal and other internationally set standards. The tracker is an attempt to showcase the nature of state regulation of disinformation in sub-saharan Africa and provides a basis for tackling this scourge.”

CIPESA said: “Speculation, false and misleading information circulating online is a challenge, not only in Africa but across the world. Legislative means against misinformation often undermine free speech and media. The tracker is a great resource for activists, to drive evidence based advocacy, policy engagement and litigation.”

GPD said: “Governments around the world have been grappling with how to respond to disinformation—a challenge given new urgency by the COVID-19 crisis. However, many of their responses pose real risks for freedom of expression. We hope that this tracker will support groups in the Africa region working to promote approaches to the disinformation challenge that protect fundamental human rights.”

PROTEGE QV said: “It is the responsibility of states to protect the security of their citizens, in the online space just as in the offline. Among threats to security online, disinformation has particular prominence, and can carry severe consequences. In seeking to tackle it, governments should balance the need to maintain security by promoting accurate information to citizens with the attendant risk of suppressing legitimate forms of expression. This tracker will serve as a key resource for groups working to ensure citizens have access to timely and accurate information.”

African Internet Rights Alliance (AIRA) Denounces Restrictions on Freedoms in Kenya and Nigeria

Joint Letters |

The African Internet Rights Alliance (AIRA) has expressed deep concern about the use of cybercrimes legislation to restrict rights and freedoms in Kenya and Nigeria. In turn, the alliance has petitioned the Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression and Access to Information in Africa, and the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression to help redress the situation in the two countries.

AIRA has urged the two Special Rapporteurs to publicly call on the governments of Kenya and Nigeria to ensure that their cyber-crimes laws do not restrict fundamental rights and freedoms during the Covid-19 pandemic.

See letter to the African Special Rapporteur and to United Nations Rapporteur

The alliance raised concerns about Nigeria’s Cybercrimes (Prohibition, Prevention, etc) Act and Kenya’s Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes Act (or CMCA, 2018) – also known as the “fake news” law. For both countries, the alliance noted that during the Covid-19 period freedoms, particularly movement, access to courts, as well as economic and social rights, are being curtailed due to the extraordinary powers held by the governments.

In Kenya, concerns were raised on misinformation and Covid-19 as well as on cyber-harassment. An example is the vaguely worded cyber harassment provision under section 27 of the CMCA, 2018, which has granted the Kenyan government the power to prosecute people for voicing their concerns and opinions. This provision has the potential to lead to convictions for single and one-off, rather than repeated, communication(s).

Meanwhile, AIRA stated that Nigeria had taken a similar stance as Kenya where in the 2015 Cybercrimes law also includes the criminalisation of single incidents of “annoying communication”. According to the alliance, this is a threat to legitimate expression which has already had a chilling effect on civic space and digital rights in Nigeria.

The alliance recognises the need to combat economic crimes committed using digital technologies, as well as the need to curb misinformation during this public health pandemic. However, AIRA also noted that the cybercrimes laws in Kenya and Nigeria had created instruments which enable authorities to arbitrarily monitor and regulate the activities of internet users and to control free expression online, in the absence of adequate safeguards.

About AIRA: The Africa Internet Rights Alliance (AIRA) undertakes collective interventions and executes strategic campaigns that engage the government, private sector, media and civil society to institute and safeguard digital rights. The alliance is made up of nine civil society organisations based in countries across Sub-Saharan Africa, including Amnesty International, ARTICLE 19 Eastern Africa, BudgIT, the Centre for Intellectual Property and Information Technology Law (CIPIT), the Co-Creation Hub (CcHub), the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA), the Kenya ICT Action Network (KICTANet), the Legal Resource Centre (LRC) and Paradigm Initiative.

CIPESA Joins Call Urging Burundi Gov't To #KeepItOn During Elections

Joint Letter |

The Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) has joined 30 international human rights advocacy groups of the #KeepItOn coalition in urging authorities in Burundi to ensure that the May 20, 2020 elections will be void of any network disruption of digital communications and to enable voters to freely elect their leaders.

The state of internet freedom in Burundi has been precarious due to the continued tightened control over independent media and critical online publishers by the government. See the 2019 report on the State of Internet Freedom in Burundi

The coalition has submitted a joint letter to the government of Burundi to ensure open, secure and stable access to the internet and social media platforms throughout the country’s presidential elections. The signatories appealed to the authorities in Burundi to consider the following recommendations to guarantee citizens’ active participation in the elections:

- Ensure that the internet, including social media and other digital communication platforms, remains accessible throughout the elections

- Ensure that the Agence de Régulation et de Contrôle des Télécommunications (ARCT) and the Conseil National de la Communication take all the necessary regulatory measures to ensure internet service providers (ISPs) inform people of any form of disruption or interference in the provision of internet access

- Order the unblocking of all websites of independent media outlets that are currently inaccessible in the country

. Read the joint letter.