By Evelyn Lirri |

Across Africa, the proliferation of digital technologies is being matched by state measures that negate the right to privacy. The accelerated adoption of digital technologies has come with increased collection and sharing of large quantities of personal data, which is a major concern as several countries lack data privacy laws and many that have them are not implementing the laws.

As a result, the right to privacy has come under growing siege, which is in turn negatively impacting the enjoyment of other rights, including freedom of expression, association, and access to information online.

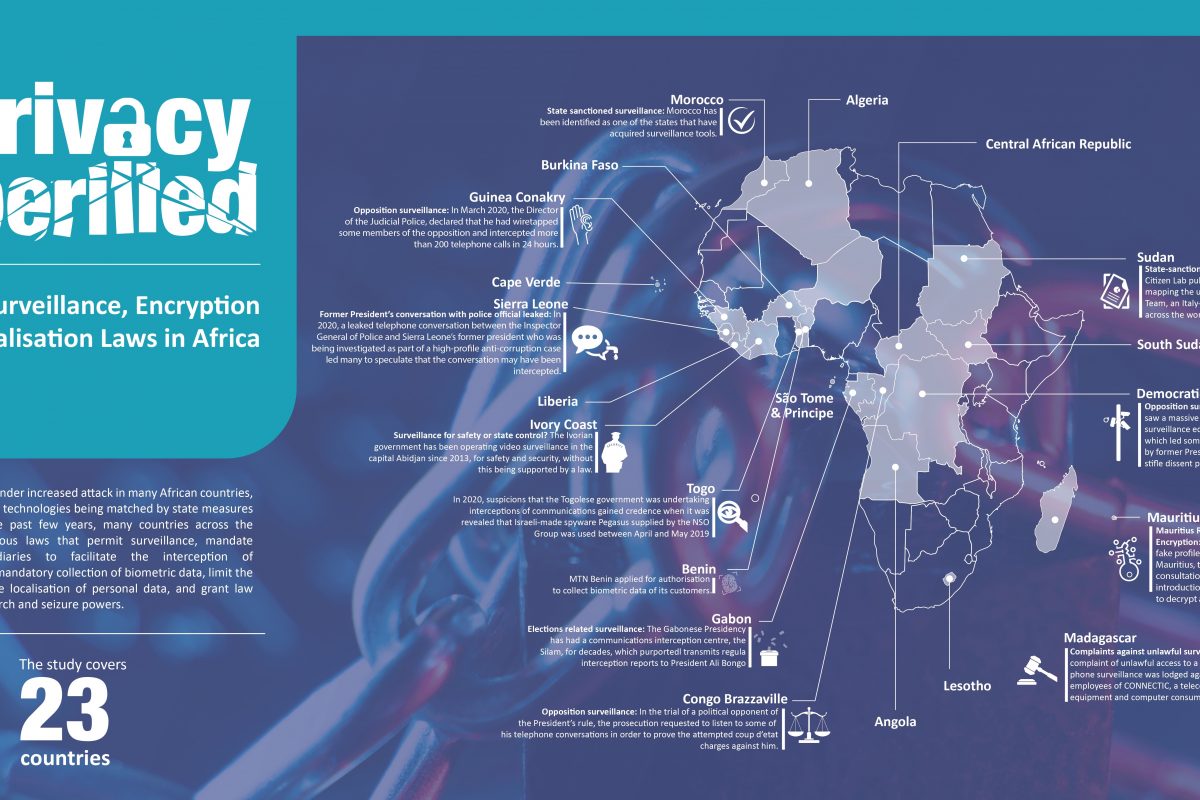

In this report, the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) analyses country-specific laws that various governments on the continent have enacted and how they impact privacy and data security through surveillance, restrictions on encryption, data localisation, and biometric databases. The report covers 23 countries – Algeria, Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cape Verde, the Central Africa Republic (CAR), Congo Brazzaville, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Gabon, Guinea Conakry, Ivory Coast, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, Sao Tome and Principe, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, and Togo.

According to the report, governments across the continent continue to collect and process personal data, intercept communications and permit surveillance without putting in place the requisite oversight mechanisms and adequate remedies, despite being signatories to regional and international conventions that recognise the right to privacy and provide safeguards for data protection, such as the revised Declaration of Principles of Freedom of Expression and Access to Information in Africa, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Weak Oversight of Surveillance Operations

One of the emerging concerns is the lack of independent judicial oversight over surveillance operations. In some countries, surveillance operations are entirely carried out and overseen by bodies within the executive, with parliaments and courts of law excluded. In Lesotho, interception warrants may be issued by the Minister responsible for the National Security Services, while in Niger, interception is ordered by the President. In South Sudan, this responsibility is vested with the Director General of the National Security Service, while in The Gambia it lies with the Minister of Interior. In Togo, the Prime Minister, and the Ministers responsible for the economy and finance, defence, justice, and security and civil protection can trigger interception of communications.

In countries such as Benin, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Morocco, Niger, and Togo, justification for surveillance is specified under the law. The reasons provided include the preservation of national security or defence, investigation of crimes, prevention of terrorism, organised crime, and activities that undermine public peace or public order. However, these crimes are not defined or are vaguely defined, which gives latitude to state authorities to broadly interpret the laws in undermining the rights of critics and opponents.

Limitations on Encryption

The use of encryption is critical in helping citizens to protect their data and communications while enjoying the right to privacy and freedom of expression. In several countries, however, this right is being threatened as governments impose restrictions that require the registration of encryption service providers, ban certain types of encryptions, and compel service providers to hand over decrypted data.

In Algeria, individuals and organisations that want to acquire and use encryption services must be granted authorisation by the country’s Regulatory Authority of Post and Electronic Communications. On the other hand, in countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Central Africa Republic, Niger, Benin, Guinea Conakry, Ivory Coast, Congo-Brazzaville, Morocco, Togo and Burkina Faso, an authorisation may be sought if the encryption is not exclusively for providing authentication or integrity control functions. Failure to seek authorisation or using prohibited encryption could attract a heavy penalty including jail time, a fine, or both.

Countries like Mali, Tanzania, and Malawi also require service providers to disclose specific software to be used for encryption. Such prohibitive provisions undermine privacy and freedom of expression that access to encryption accords.

Compelled Assistance by Service Providers

Governments are also using compelled assistance – where state agencies seek access to data from service providers, including through courts of law and regulators, to gain access to individuals’ private data. This includes access to the secret code of encrypted data, or to decrypted data, and generally requiring service providers to render assistance to state agencies in the interception of communications.

Laws in countries like Benin, Ivory Coast, Congo-Brazzaville, Gabon, Guinea Conakry, and Sierra Leone specify grounds on which the state can access encrypted data of individuals and also facilitate lawful interception of communications. Laws in several countries require intermediaries such as telecom companies and Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to facilitate surveillance.

As the report notes, compelled service provider assistance as stipulated in some countries’ laws is quite worrisome as it gives governments and their agencies unfettered access to individuals’ private data beyond limits prescribed by law or permissible by international standards.

Data Localisation

Various countries have enacted laws to control the cross-border transfer of personal data for a multitude of reasons, including national security, personal data protection, and data sovereignty. Algeria, Niger, Morocco, Benin, Cape Verde, Madagascar, Guinea Conakry, Ivory Coast, Congo Brazzaville, Sao Tome & Principe and Togo have laws that prohibit cross-border transfer of personal data unless authorised by data protection authorities.

However, as the report’s findings show, despite having laws in place, enforcement remains weak. Further, data localisation requirements could, in the absence of robust legal and practical safeguards, further facilitate efforts by state and non-state actors to undermine privacy-related rights. Morocco, Algeria, and Ivory Coast are some of the countries where data localisation measures are being implemented.

Biometric Data Collection

Recent years have seen a number of African countries undertake mass collection, processing and storage of personal data through initiatives such as mandatory SIM card registration, electronic biometric passports, IDs, and driving licences. Although many countries have also passed laws on data protection and privacy, weak implementation mechanisms, coupled with the absence of the requisite safeguards, remain a threat to individual privacy. This is particularly so in instances where regulatory authorities have the power to direct telecom operators to hand over information such as that contained in the SIM card databases.

Furthermore, the existing oversight mechanisms and provisions for remedies in the case of data breaches have not been effective enough to protect the personal information and communication of individuals in line with internationally recognised human rights standards. Many countries have enacted data protection laws but have additional legislation that gives the state and its agencies power to access citizens’ biometric information, often under the guise of protecting national security. This is the case with countries such as Kenya, Gabon, Uganda, Lesotho, Mauritius, Morocco, Niger, Sao Tome, Togo, Algeria, Congo Brazzaville, and Ivory Coast.

Recommendations

Government:

- Enact data protection laws in countries such as Liberia, Sierra Leone and South Sudan to provide for and guarantee protection of personal data.

- Review existing laws, policies and practices on surveillance, including COVID-19 surveillance, biometric data collection, encryption and data localisation, to ensure they comply with article 9 of the African Charter and with the principles in the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information in Africa 2019.

- Cease blanket compelled service provider assistance and provide for clear, activity-bound and court-mandated assistance.

- Submit periodic reports to the different international human rights treaty body monitoring mechanisms such as the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, the Human Rights Committee and the Universal Periodic Review process, on the measures taken to guarantee the right to privacy and data protection.

Civil Society:

- Work collaboratively with stakeholders such as the private sector and academia, including through litigation to challenge laws and measures that violate privacy rights.

- Monitor and document privacy rights violations through evidence-based research.

- Conduct regular analysis of proposed laws to identify the gaps and propose revisions before they are enacted into law.

- Advocate for the promotion and protection of the right to privacy and data protection through various advocacy engagements.

Private Sector:

- Develop, publish and implement internal privacy and data protection policies and best practices in handling customer data so as to guarantee customers’ data protection and privacy.

- Regularly publish transparency reports that highlight all cases of personal data and information disclosure to government agencies as well as other assistance offered to governments to enable communication interception and monitoring.

- Develop technologies and solutions and use privacy-enhancing technologies that embed and integrate privacy principles by design and default.

- Comply with the United Nations Business and Human Rights Principles by conducting human rights impact assessments to ensure that measures undertaken do not harm individual rights to privacy and data protection.

Find the full report here: Privacy Imperilled: Analysis of Surveillance, Encryption And Data Localization Laws in Africa

See another CIPESA report Mapping and Analysis of Privacy Laws in Africa that maps privacy-related laws in 19 other countries.