By Digital Shelter |

Digital inclusion is often framed as access and numbers – how many people are trained, device ownership, and how many users are connected. In Somalia, however, the reality is far more complex. While recent data suggest that internet penetration has reached approximately 55 percent of the population, and there are over 10 million internet users, social media adoption remains low and skewed toward male users, with women constituting a smaller proportion of those who are online.

Meanwhile, the political and civic space remains constrained. Due to protracted conflict, fragmented governance and insecurity, Somalia is classified as “Not Free” in global democracy assessments. The country also ranks near the bottom in press freedom indices, with journalists and media houses facing threats, harassment, arbitrary closures, and censorship pressures, particularly in conflict-affected regions, making open expression online and offline perilous.

Young Somali women are joining digital spaces shaped by these fragile conditions, coupled with unequal power relations and persistent safety concerns. Many are navigating unstable job markets, expectations to contribute to family livelihoods, and social norms that continue to question women’s visibility and voice, both online and offline. In such a context, digital upskilling is not merely technical but rather deeply social, economic, and political. If approached narrowly, it risks reproducing existing exclusions by focusing only on tools and outputs.

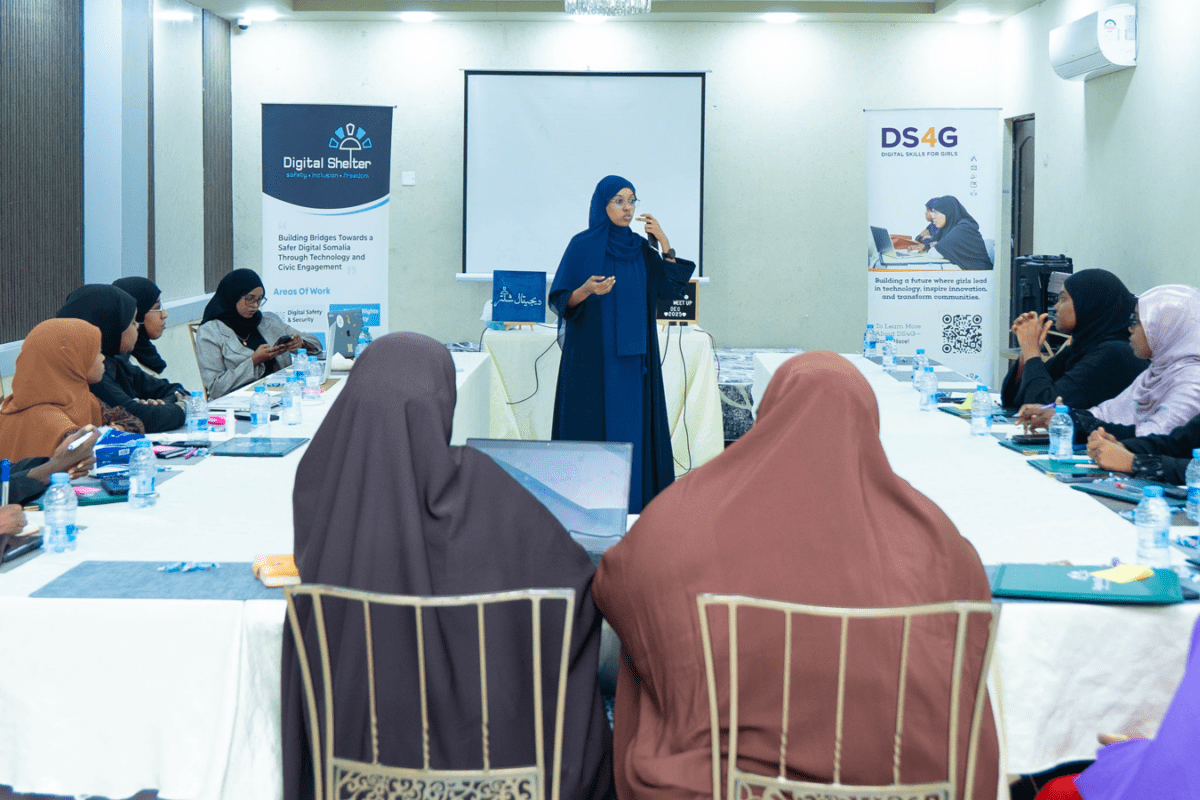

The Digital Skills for Girls (DS4G) programme by Digital Shelter is designed with this in mind, treating digital skilling and inclusion not as isolated competencies but as entry points into broader questions of participation, agency, and voice within Somalia’s evolving digital ecosystem. Combining practical digital skills, digital safety and rights awareness, DS4G has supported 35 women and girls, conducted monthly meet ups and stakeholder engagements to empower young Somali women.

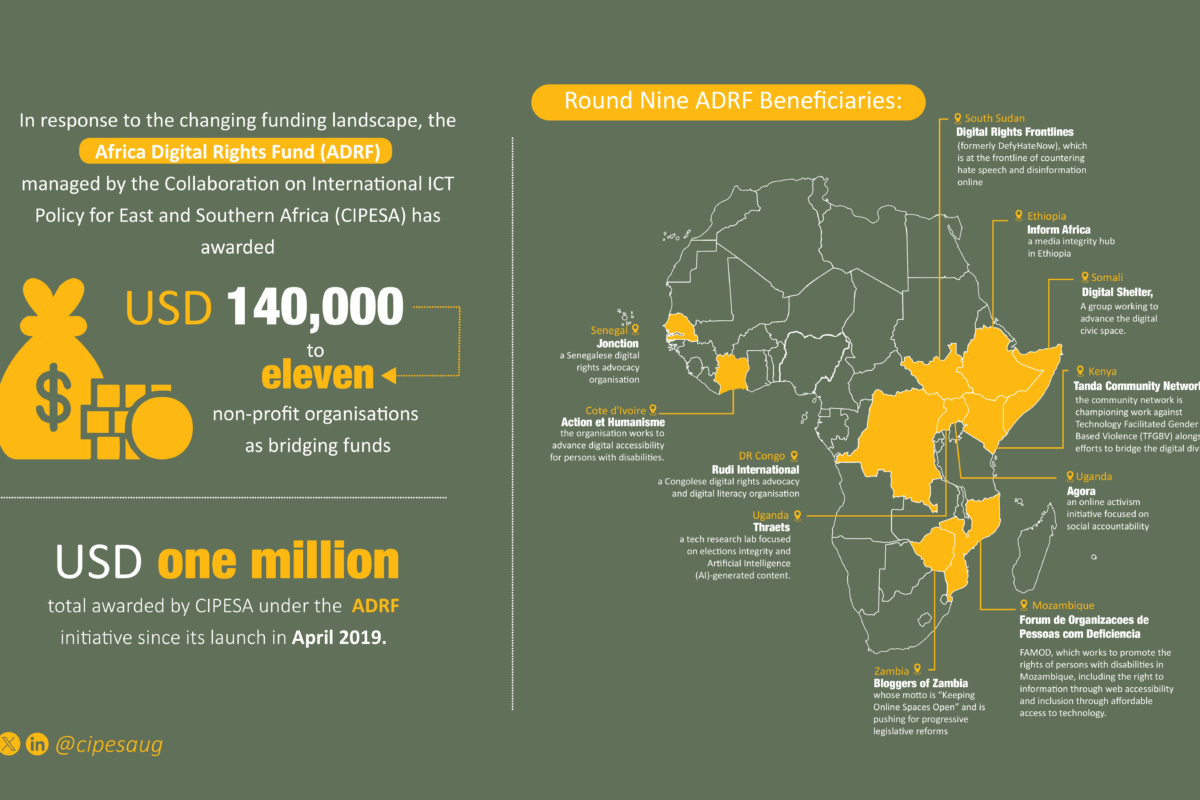

With initial funding from AccessNow in 2024, the US funding cuts affected the continuity of DS4G. A discretionary award under the Africa Digital Rights Fund (ADRF) – an initiative of the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA)—supported continued implementation through 2025.

As noted by Ali, “At a time when many organisations were forced to scale back activities due to funding instability, CIPESA’s discretionary support allowed Digital Shelter to remain operational and responsive, ensuring that young women continued to access skills and learning spaces designed to support meaningful participation in digital, social and civic life”. He added that through DS4G, Digital Shelter had strengthened its role as a trusted, women-centered digital rights actor with a replicable programme model.

The DS4G’s sessions included graphic design, personal branding, emerging technologies, data protection and privacy, online threats and risks, and career development. A key component of DS4G was the Cyber Safety for Women event, which reinforced digital safety as a collective concern. The event featured a documentary screening on lived digital experiences and panel discussions on gender, online safety, and participation.

“DS4G recognised that technical skills alone are insufficient unless young women are also equipped to navigate digital environments safely, communicate confidently and position themselves for future opportunities,” said Digital Shelter’s Executive Director, Abdifatah Ali.

According to Digital Shelter, the inclusion of graphic design in the DS4G programme was a strategic one. The team argues that sitting at the intersection of creativity, communication, and influence, design shapes how information is interpreted, whose stories are amplified, and which messages gain traction. For the participants of DS4G, many of whom were students or recent graduates, it offered an accessible entry into digital work.

“As the training progressed, participants moved beyond executing tasks to interrogating purpose and impact, asking who messages are for, what they communicate, and how design can support causes, campaigns, and community conversations,” said Ayan Khalif, Digital Shelter’s Program Manager.

Indeed, participant feedback reflects positive outcomes – both skills acquisition and agency. “Before this project, I used social media without thinking much about safety. Now I understand how to protect myself online and how important digital security is for women like us,” said one participant. As part of reflection exercises, participants explored how design could support community initiatives, advocacy efforts and communicate messages. Another participant stated, “The monthly meetups helped me gain confidence. Speaking in front of others was difficult at first, but now I feel more comfortable expressing my ideas.”

The DS4G initiative has empowered a cohort of young women to navigate digital spaces with confidence and security, equipped with skills to exploit economic opportunities, advocate for change, and engage safely and confidently in community affairs.