By Edrine Wanyama

Digital and physical surveillance by states, private companies that develop technology or supply governments and unscrupulous individuals globally and across Africa is a major threat to the digital civic space and operations of civil society organisations (CSOs), human rights defenders (HRDs), activists, political opposition, government critics and the media. The highly intrusive technology, which is often facilitated by biometric data collection systems such as for processing of national identification documents, voter cards, travel documents, mandatory SIM card registration and the installation of CCTV cameras for “smart cities”, adversely impacts the digital civic space.

Given these developments, the Digital Rights Alliance Africa (DRAA), a network of CSOs, media, lawyers and tech specialists from across Africa that seeks to champion digital civic space and counter threats to digital rights on the continent, recently held a learning session on “Understanding Surveillance Trends, Threats and Challenges for Civil Society.” The Alliance was created by the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL) and the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) in response to rising digital authoritarianism. It currently has members from more than 12 countries, who collectively conduct research and advocacy and share experiences around navigating digital threats and influencing strategic digital policy reforms in line with the alliance’s outcome declaration.

The virtual learning session built capacity among the Alliance members to better understand digital surveillance and the related threats facing democracy actors. Discussions delved into the nature of surveillance, the regulatory environment, and strategies to navigate and counter surveillance risks and threats. The threats and risks include harassment, arbitrary arrests, persecution and prosecution on trumped up charges.

While emphasising the need to understand emerging surveillance technologies, ecosystem and deployment tactics, Richard Ngamita, the Team Leader at Thraets, highlighted the huge investment (estimated at USD 1 billion annually) which African governments have made in acquiring surveillance technologies from China, Israel, the United States of America and Europe. Ngamita urged CSOs, HRDs and other actors to build digital security capacity to protect against illegal surveillance.

Victoria Ibezim-Ohaeri, the Executive Director of Spaces for Change, while referencing the Proliferation of Dual-Use Surveillance Technologies in Nigeria: Deployment, Risks & Accountability – Spaces for Change report, highlighted weak regulation and unaccountable practices by states that facilitate unlawful surveillance across the continent and their implications on rights. According to the report,

“The greatest concern around surveillance technologies is their potential misuse for political repression and human rights abuses. Surveillance practices also undermine the citizens’ dignity, autonomy, and security, translating to significant reductions in citizens’ agency. Agency reductions are magnified by the state’s power to punish dissent. This creates a chilling effect as citizens self-censor or avoid public engagement for fear of being surveilled or punished. The citizens have little agency to challenge or resist the state’s surveillance because of low digital literacy, poverty and broader limitations in access to justice.”

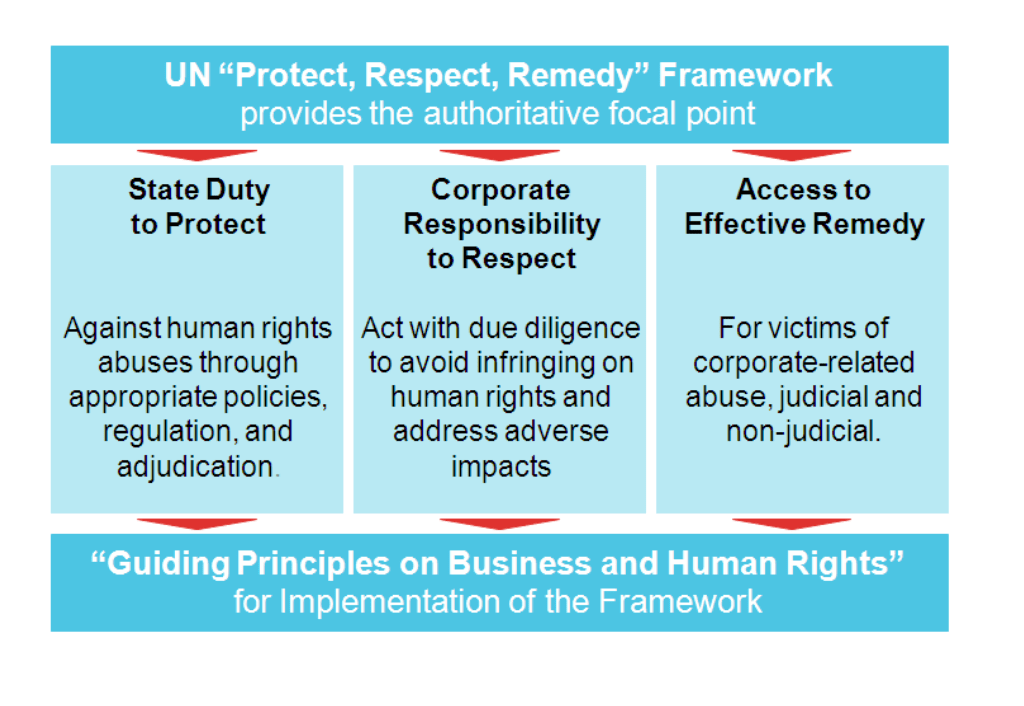

Michaela Shapiro, the Global Engagement and Advocacy Officer at Article 19, United Kingdom, discussed the governing norms of surveillance globally while paying particular attention to the common gaps that need policy action at the country level in Africa. Recalling the intensification of digital and physical surveillance as part of state responses to curb the spread of Covid-19 in the absence of clear oversight mechanisms, Michaela emphasised the role of CSOs in advocating for data and privacy protection.

To-date, the leading instrument of data protection on the continent, the African Union Convention on Cyber Security and Personal Data Protection has only 16 ratifications out of 55 states, while only 36 states have enacted specific laws on privacy and data protection rights.

Surveillance in Africa generally poses a major threat to individuals’ data and privacy rights since governments exercise wide access over the data subjects’ rights. National security and the loopholes in the laws are usually exploited to abuse and violate data rights. While there are regional and international standards, these are often overlooked with governments taking measures that are not provided for by the law, rendering them unlawful, arbitrary and disproportionate under human rights law.

By way of progressive actions, speakers noted and made recommendations to States and non-state actors to the effect that:

States and Governments

- Address surveillance and bolster personal data and privacy protections through adopting robust legal and regulatory frameworks and repealing restrictive digital laws and policies.

- Promote and enhance transparency and accountability through the establishment of independent surveillance oversight boards.

- Strictly regulate the use of surveillance technologies by law enforcement and intelligence agencies to ensure accountability.

- Collaborate with other countries to develop harmonised privacy standards within the established regional and international standards to have settled positions on cross-border controls on surveillance.

Civil Society Organisations

- Build and enhance capacities of HRDs and other players in data governance and accountability to equip them with knowledge to counter common data privacy threats by governments and corporate entities.

- Push for ethical and responsible use of technology to prevent and minimise technology-related violations.

- Challenge all forms of unlawful use of surveillance practices through legal action by, among others, taking legal actions.

Tech Sector

- Conduct regular audits and impact assessments to address potential privacy breaches and enhance accountability and transparency.

- Prioritise privacy and integrate privacy protections into their products and services including data collection minimisation and establish strong security measures for privacy.

- Prioritise ethical considerations in the development and deployment of new technologies to guarantee strong protections against potential violations.