By Daniel Mwesigwa |

Last year, Uganda’s communications regulator commissioned a study to establish the status of access and usage of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) by Persons With Disabilities (PWDs). In response to a call for comments, CIPESA made submissions to the commission, which could help various government agencies to devise strategies that meaningfully improve usage of digital technologies by PWDs.

According to Uganda’s statistics bureau, persons with disabilities comprise 16% of the country’s population of 37.5 million. However, they face various limitations in accessing and using ICT tools and services. The draft report of the study commissioned by the Uganda Communications Commission (UCC) shows that national ownership of a radio and a mobile phone among PWDs was high at 70% and 69% respectively. Ownership of fixed-line telephones, desktop computers and laptops was very low at 0.5%, 1% and 3.9% respectively. However, 15% of respondents’ households had access to the internet.

Below are highlights from CIPESA’s submission:

1. Disaggregate results by type of disability

While the report highlights respondents’ type of disability (61% had a physical disability, 31% were visually impaired, and 2% had a hearing impairment), it does not show how the nature of disability affects access and usage of ICT. Persons with disabilities are not a homogeneous group and the nature of disability influences how they may perceive, be able to access and to use ICT. It may not be possible therefore to address the distinct needs of different categories of PWDs if data is not disaggregated by type of disability – as indeed it should be disaggregated based on gender, location, income, among other demographics.

2. Comparative analysis of data

The report provides ICT access and usage figures for PWDs (e.g. 69.4% mobile phone ownership; 3.9% had laptop computers and 1% desktop computers; 15% of households had access to the internet). However, these numbers need to be presented and analysed alongside overall national statistics on access and usage if they are to offer direction on the remedial actions needed.

3. Taxes deepening exclusion

Only 14% of respondents had access to a bank account compared to 86% that accessed financial services through other mechanisms such as mobile money, and village savings and loan associations. One third (33%) had access to mobile money, which is lower than the national average of 55%. Further, 41% of the respondents lacked access to any form of financial services, compared to the national average of 22% that is financially excluded.

Worryingly, majority of PWDs (66%) said their use of social media had reduced with the introduction last July of the Over The Top (OTT) tax, while 26% said they were no longer using social media. Only 8% had not changed their usage levels. According to the report, 52% of PWDs access social media on their phones, while 12% access it on their computers.

As CIPESA has previously found, OTT platforms and mobile money networks had considerably eased the lives of PWDs. For example, platforms like WhatsApp were used to disseminate critical information among individuals with hearing impairment before the added cost of using social media rendered them unaffordable to many, who already faced challenges in finding employment and often relied on financial support from others. For UCC and other relevant Uganda Government institutions, these findings should not be taken lightly and should inform policy in this area.

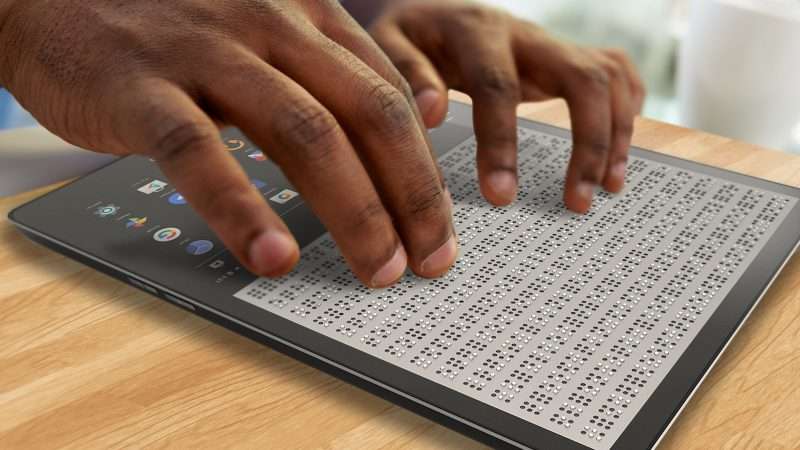

4. Awareness and usage of assistive technologies

Assistive technologies are products, devices, or equipment, used to maintain, increase, or improve the functional capabilities of individuals with disabilities. A very concerning finding in the Report is that 76% of PWDs were not aware of the low-cost Assistive Technologies like manual Perkins Brailler, hand-held magnifiers, hand frames/slates and communication boards. Only 14% of respondents were aware of the Perkins Brailler yet its usage was low at 4%. Just 13% of the respondents were aware of magnifiers yet only 2% used them. Issues of awareness of these technologies, their cost and availability, are apparent. The UCC should offer subsidies for assistive technologies through the universal service access fund, the Rural Communications Development Fund (RCDF).

5. Privacy and data protection

The right to privacy is a core entitlement for every individual under article 27 of the Uganda Constitution. The Persons With Disabilities Act, 2006, section 35 protects PWDs from arbitrary or unlawful interference with their privacy. However, the report does not assess PWDs awareness of their privacy rights or data security skills. Such an assessment is necessary to inform remedies including on capacity development.

6. Public and private sector compliance

Consistent with international conventions and instruments such as the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as well as domestic laws such as the national constitution, Persons With Disabilities Act 2006, and the National IT and Disability Policy, the emphasis on inclusion and non-discrimination for PWDs cannot be overlooked if the country is to attain her development goals.

As the government works towards implementing the ICT and Disability Policy, the emphasis on Website Accessibility Guidelines (WAG) can be fast-tracked by auditing compliance with the 2014 ‘Guidelines for Development and Management of Government Websites’ which were developed by the National Information Technology Authority Uganda (NITA-U). Entities that do not comply with universal accessibility standards should be sanctioned.

Further, the Equal Opportunities Commission, working with other relevant entities, should require government ministries, departments and agencies (MDAs) and private enterprises which offer public services to prepare annual statements in which they report on how they have worked towards increasing accessibility and inclusiveness for PWDs.

The full submission can be read here.