By Netblocks’ Writer |

At the 2018 Forum for Internet Freedom in Africa in Accra, Ghana, NetBlocks is demonstrating new tools and methodologies to defend human rights, empowering local communities and creating a space for open and progressive policies for internet access and telecommunications.

In a joint panel on data-driven advocacy on Friday, NetBlocks along with partners Access Now, CIPESA, the GNI and ISF, soft-launched the Cost of Shutdown Tool, an initiative supported by the Internet Society which enables participants to calculate the economic cost of internet shutdowns, network disruptions and platform blocking in sub-Saharan Africa. Economic arguments have proven to be an effective means to bolster the case for human rights online with a view to development and prosperity, a trend which is being recognised and made accessible to internet freedom campaigners by way of the new initiative.

Internet shutdowns & other connectivity restrictions have far-reaching impacts on internet users & society. This exciting tool from @netblocks estimates their economic cost: https://t.co/bQzDxdjFuC #KeepItOn

— Freedom on the Net (@freedomonthenet) September 28, 2018

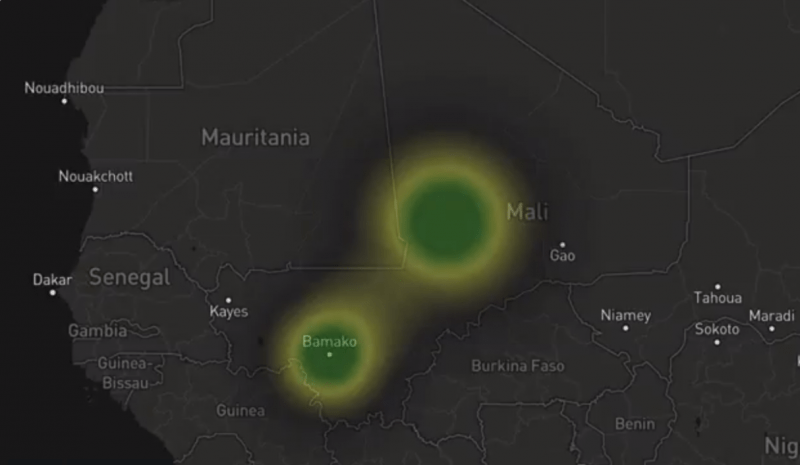

The panel explored how communities have been adopting new tools and developing new workflows as part of the KeepItOn initiative to support internet freedom across the continent, documenting recent incidents of network disruptions during elections in Mali and in Chad, as well as collecting bodies of technical evidence around disruptions in Ethiopia and Cameroon at critical moments for democracy and society.

@netblocks and media freedom groups just demo-ed a cool” Cost of Shutdown” realtime tool that tracks internet shutdowns and their economic cost at #FIFAfrica18 #InternetFreedomAfricapic.twitter.com/lHNpk2mzIk

— Charles Onyango-Obbo (@cobbo3) September 28, 2018

Thursday saw the launch of the latest edition of The Internet Measurement Handbook, which provides civil society organisations and human rights defenders with practical technical and policy advice on managing internet disruptions, with a copy provided to each FIFAfrica participant.

NetBlocks director Alp Toker and advocacy manager Hannah Machlin demonstrated new internet freedom measurement techniques which present a more accurate, live view of emerging network incidents. Demonstrations and workshops provided a hands-on introduction to real-time internet freedom monitoring, web probes and internet-scale visualisation, which are now being adopted across the continent and globally as part of the internet observatory project.

@netblocks present tools to measure #InternetShutDowns at the #FIFAfrica18. #KeepItOn#InternetFreedomAfrica pic.twitter.com/50EAmDqRcL

— Emmanuel Vitus (@emmavitus) September 29, 2018

Working with other civil society groups, the team explored issues around internet governance, internet protocols and their impact on human rights, free expression and trade, producing a series of new alliances and partnerships to strengthen digital rights and protect the integrity of elections regionally and worldwide.

Check @netblocks – keeping the internet on 💪🏽💪🏽

A key player in #InternetFreedomAfrica

Exhibiting at #FIFAfrica18 #ChangeAfrica pic.twitter.com/JnyQ4CNU5F— Maria Sarungi Tsehai (@MariaSTsehai) September 28, 2018

Connecting data and human rights

Sessions over the course of three days have helped build a bridge between technical work to track restrictions on free expression online, connecting the personal experiences of victims of human rights violations with policy makers, governments and ICT industry stakeholders.

“Just two weeks ago the internet in #Ethiopia was shut down and thousands were arrested and taken to military camps” explain @zone9ners at #FIFAfrica18. Matches technical evidence we collected of mobile cell disruptions in Addis #KeepItOn pic.twitter.com/J09E5gRwBB

— NetBlocks.org (@netblocks) September 27, 2018

About FIFAfrica

Organised by the Collaboration for International ICT Policy in East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) in partnership with the Media Foundation West Africa (MFWA) the 2018 edition of the Forum on Internet Freedom in Africa takes place on 26-28 September 2018 in Accra, Ghana.

The Forum is a landmark event that convenes various stakeholders from the internet governance and online rights arenas in Africa and beyond to deliberate on gaps, concerns and opportunities for advancing privacy, access to information, free expression, non-discrimination and the free flow of information online on the continent.

With strategic linkages to other internet freedom forums and support for the development of substantive inputs to inform the conversations on human rights online happening at national level, at the African Union and the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights (ACHPR), the African Internet Governance Forum (IGF), subregional IGFs, the global IGF, Stockholm Internet Forum (SIF), the Internet Freedom Festival (IFF), the Internet Freedom Forum (Nigeria) and RightsCon, among others, FIFAfrica provides a pan-African space where discussion from these other events can be consolidated at continent-wide level, drawing a large multistakeholder audience of actors.

Check out this AMAZING new tool created by @netblocks based on a @cipesaug methodology that estimates the cost of an internet shutdown has in a given country or region — https://t.co/ZDJDe1HyCx#FIFAfrica18 #keepiton #netdemocracy #digitalrights #netfreedom #mediadev

— Daniel O’Maley (@domaley) September 28, 2018