By Khattab Hamad and CIPESA Writer |

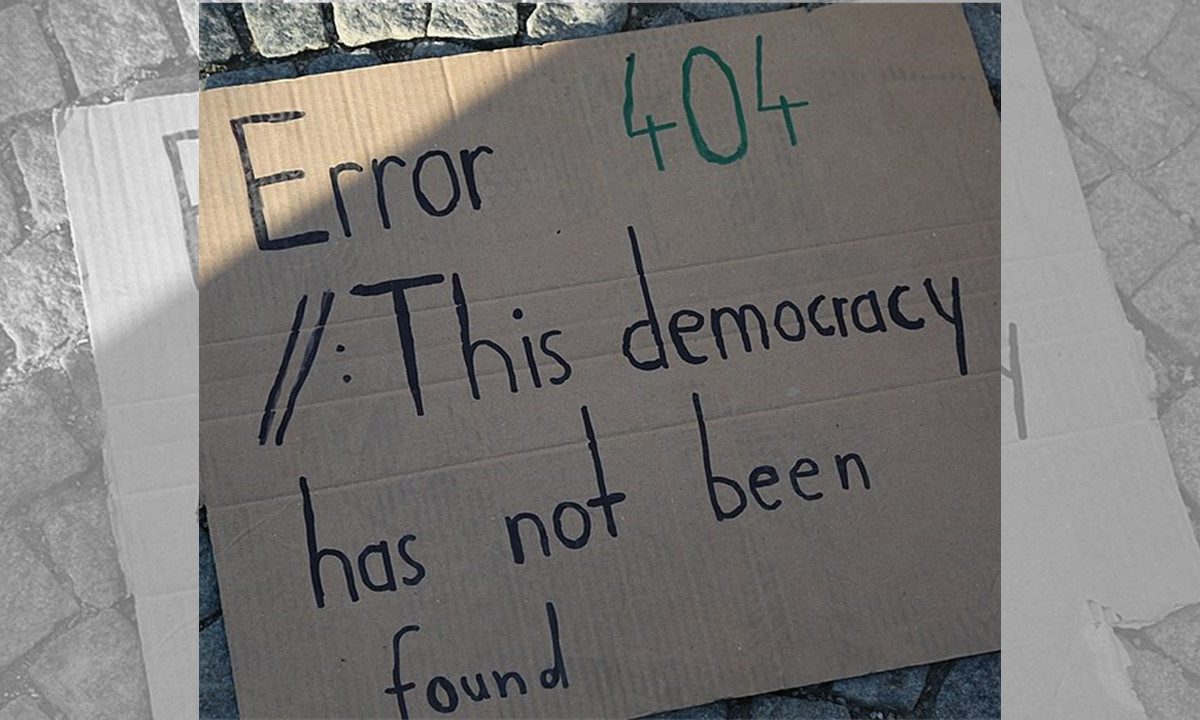

On December 19, 2021, the third anniversary of the start of the uprising that overthrew former Sudanese strongman Omar al-Bashir, protests against the current military rulers rocked the capital Khartoum. Yet these demonstrations are only a small part of the north African country’s challenges, as it remains saddled with a slew of repressive laws that undermine civil liberties, with the digital civic space particularly under attack.

Sudan’s 2019 constitution grants citizens the right to privacy (article 55) and to free expression (article 57) and “the right to access the internet” (article 57(2)). As of December 2020, Sudan had 34.2 million mobile subscriptions while internet subscriptions stood at 13.7 million, representing a penetration of 31%. Sudan has the most affordable mobile internet in Africa and is ranked among the five least expensive countries for mobile internet globally.

Despite the constitutional guarantees and proliferation of technology, a new briefing paper by the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) shows that the state of digital rights remains precarious, with the cybercrimes law enabling the military rulers to harass dissenters and critics under the guise of fighting false information online.

Frequent internet shutdowns remain a constant reminder that the government will go to great lengths to control access to and use of digital technologies for mobilisation. In the last three years, six internet disruptions have been recorded, mostly ordered to thwart public protests against bad governance. The disruptions have had significant economic implications and only ended following the intervention of the courts.

The brief explores the repressive elements of media and technology-related laws and how they have been used to undermine freedom of expression, access to information and press freedom in the aftermath of al-Bashir’s overthrow. Overall, while there have been some improvements since al-Bashir’s ouster, the current government continues to institute regressive measures such as news website blockages and censorship. The latest power machinations that saw the military stage a coup on October 25, 2021 are making matters worse.

The Sudanese Professionals’ Association (SPA), which spearheaded the uprising that overthrew al-Bashir, extensively used digital technologies to disseminate news about the uprising and to mobilise citizens to attend protests. The military rulers that succeeded Bashir seem to have realised the power of technology in mobilisation and embarked on continuous disruption of the internet, in addition to instituting other measures to curtail online organising, freedom of expression, and the free flow of information online.

Bashir’s dictatorship initiated internet disruptions in view of public protests calling for his overthrow, but the government that succeeded him has been more prolific in utilising shutdowns to try and shut off criticism and protests.

The longest internet disruption in Sudan’s history was recorded in 2019 and lasted 37 days. During protests around the time the shutdown was initiated, more than 100 protesters were killed. The latest shutdown started on October 25, 2021 and lasted 25 days. It was instituted after Lt. Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan seized control of the government. The shutdown was ended by a court order on November 11.

In July 2021, Sudanese authorities blocked more than 30 local news websites in the run up to protests demanding the resignation of the government, a move that severely undermined the right to expression and access to information.

Meanwhile, the cybercrime law of 2020 punishes publishing “lies” and “fake news” online with a heavy penalty of four years imprisonment, or flogging, or both. This law has been used by the military to silence activists and critical state officials. Even Lt. Gen. Burhan has this year invoked it to bring a suit against a prominent critic. The Press and Publications Law of 2009 equally has repressive provisions and was last August controversially invoked to suspendAlitibaha and Alsayha newspapers.

In 2020, Sudan issued the National security law amendment of 2020, article 25 of which leaves latitude for staff of intelligence agencies to violate citizens’ privacy by giving the Sudanese General Intelligence Service “the right to request information, data, documents or things from anyone to check it or take it” without a court order. Last October, military forces that staged a coup appeared to use this provision to search people’s phones in the streets to delete documentation of human rights violations perpetuated by security forces.

See the policy brief for further details on Sudan’s Bad Laws, Internet Censorship and Repressed Civil Liberties.