Open Data for improved resource allocation and effective service delivery in Uganda was the theme of the latest Africa Counts roundtable held in Kampala, Uganda on March 13, 2013. Organised by Development Initiatives (DI) and Development Research and Training (DRT), it was the fourth in a series of forums aimed at increasing opportunities for “cross-country, cross-sector and multi-stakeholder” engagements that involve citizens in decision making processes on development issues across East Africa.

The forum explored avenues through which open data can be leveraged to influence resource allocation and effective delivery of public goods and considered potential challenges to the operationalisation of an open development platform in Uganda and possible means of dealing with them. Furthermore, it argued the case for the inclusion of ‘open data’ as a stand alone goal in the post-MDG agenda.

DRT’s Paul Onapa commended the government of Uganda for having in place constitutional guarantees to the right to information, as well the Access to Information Act of 2005.

However, he said, despite having a robust legal framework, access to public information remained limited. “Public data and information management schemes are still largely paper based (available in bulky hard copies and/or online PDFs) and largely aggregated. In addition, this information is scattered in various government departments and only available to a few with adequate contacts,” said Onapa.

He added that open data, with its foundation modelled on digital technology and the internet, offers an opportunity to create a “one-stop portal/platform” where citizens can access, download, and analyse information on matters that affect them, particularly basic services and issues of value for money. With this knowledge, citizens can then meaningfully participate in improving public services.

His remarks were supported by Al Kags of the Open Institute, who stated that a “switched on, participating citizenry” is key to the success of open data as a mechanism for transparency and accountability. The Open Institute has been involved in open government initiatives in Kenya, such as Code4Kenya and africaopendata.org.

Panellists Professor Abel Rwendeire of the National Planning Authority and Margaret Kakande from the Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development) acknowledged the potential of open data to ensure effective resource allocation and service delivery. However, Kakande pointed to a number of challenges being faced by government bodies in embracing open data, such as a lack of legal frameworks on data disclosures.

Edward Ssenyange of the Democratic Governance Facility (DGF) and CIPESA’s Lillian Nalwoga highlighted ways in which citizens’ participation in open data initiatives can be enhanced: placing emphasis on capacity building in the use of ICTs, robust multi-stakeholder engagement (particularly with mainstream media), advocating for key government institutions’ commitment to openness, authenticity and relevance of data.

Currently, a civil society led Open Data platform has been created by the Uganda Open Development Partnership (see OpenDev.Ug and Data.Ug). A key objective is to share development information – on agriculture, education, health, roads sub-sector, etc – and on financial flows including all resource flows to Uganda (aid, domestic revenues, humanitarian assistance, remittances, etc). Making the information accessible and useable by various stakeholders – citizens, government officials, donors, civil society, media and private sector is another objective. CIPESA and DRT are among the founders of the Uganda Open Development Partnership.

Previous Africa Counts roundtable forums include The prospects of East Africa’s natural resource finds (July 2012, Nairobi, Kenya), The state of social protection in East Africa (October 2012, Nairobi, Kenya) and Progress in the Kenya Open Data Initiative (November 2012, Nairobi Kenya).

Outcomes of the Kampala forum will be used to develop targeted messages to inform policy and to stimulate public demand for openness in the conduct of data/information sharing in Uganda.

Balancing Freedom of Expression And Privacy

Striking a balance between freedom of expression and privacy on the internet was the focus of a panel discussion at a review of one decade after the World Summit of the Information Society (WSIS). The WSIS+10 Review meeting took place at the UNESCO headquarters in Paris, France, February 25-27, 2013.

What convergences and tensions exist between freedom of expression and privacy online? What are the implications of approaching the balance between free expression and privacy from a freedom of expression–centric point of view? What actions can governments, civil society, media and the private sector take to balance privacy with freedom of expression online? And what is the best way to empower users? These are some of the questions addressed at the session on ‘Promoting of Freedom of Expression and Privacy Online’. CIPESA’s Lillian Nalwoga was the remote moderator for the session.

The session built on earlier discussions held at the 7th Internet Governance Forum (IGF) in Baku, Azerbaijan on promoting both freedom of expression and privacy on the internet. It also drew from the Global Survey of Internet Privacy and Freedom of Expression – a UNESCO 2012 publication – which highlights a diverse international regulatory landscape, and the challenges posed by discrepancies in laws pertaining to the online and off-line spheres, and between national and international jurisdictions.

During the session, Pranesh Prakash from the India-based Center for Internet Society stressed the need for more relaxed regulations to govern the conduct of the private sector. He noted that “one must give the private sector enough leeway to safeguard them from responsibility for users’ actions and the requirement of taking down reasonable speech.” However, he added that the commercial sector has divergent interests and they do not necessarily align with public interests.

According to him, differing public and private sector interests coupled with unenforceability of self-regulation mechanisms and the jurisdictional issues of the internet mean that the conflict between freedom of expression and privacy cannot be easily resolved through public policy options that are only aimed at the private sector.

Patrick Ryan, a Policy Counsel from Google who was also a panelist, argued that the move to the “cloud” brings with it both enhanced privacy and security benefits, while at the same time putting data potentially at risk. Noting that government surveillance remained one of the biggest threats to privacy, he stressed that the private sector needs to share more information on government take down requests that violate individuals’ privacy and free speech.

Meanwhile, William Dutton, a professor of Internet Studies at Oxford Internet Institute, stressed the importance of recognising the power of the internet in empowering networked individuals and enabling freedom of expression, like never before. He cautioned that if nations do not approach the issue of striking a balance between freedom of expression and privacy appropriately, some of the key benefits of the internet may be lost. He noted that whilst some nations have taken progressive steps, many others are moving in the wrong direction and various global policy choices are increasingly restricting freedom of expression.

Indeed, this has been illustrated by worldwide trends towards more content filtering and censorship. Dutton said adopting inappropriate models for internet governance and regulation, such as disproportionate levels of surveillance in the name of security, reliance on intermediaries to regulate content, and assertion of national sovereignty and jurisdiction in the online world are threatening privacy and freedom of expression.

Key recommendations from this session were: avoiding a moral panic over privacy; creating widespread awareness of issues concerning privacy and data protection among users especially the young generation; updating policy and regulatory frameworks that address freedom of expression and privacy online; and having a clear definition on national security interests.

For more information, please visit – https://www.unesco-ci.org/cmscore/events

Promoting of Freedom of Expression and Privacy Online

Follow WSIS+10 on twitter at #WSIS

Transparency and Accountability Community of Practice Launched

The Transparency and Accountability Initiative (T/AI) has launched a community of practice to bring together development partners, civil society organisations and researchers to expand the impact and scale of transparency and accountability interventions. The launch is taking place from February 17-20, 2013 in Cape Town, South Africa.

Participants from across the world are exploring ways of sharing knowledge and support on where, when and how technology interventions can generate change.

CIPESA is excited to be taking part in the launch and understanding how this community of practice could add value to the work we are doing in the transparency and accountability field, in particular ICTs for Democracy and Open Data and eGovernment.

Read more about T/AI and the community of practice here.

Follow the proceedings on Twitter at #TAlearn.

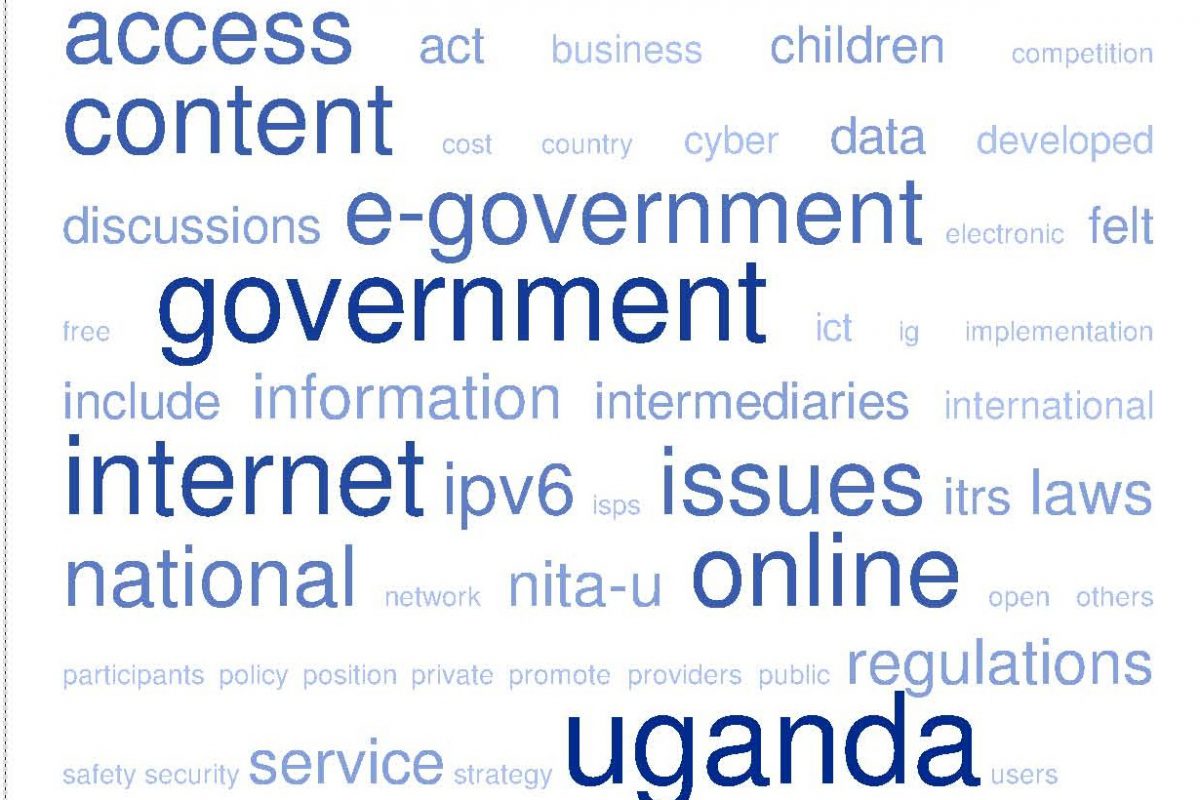

2012 Uganda National IGF Report

The report of the 5th Uganda Internet Governance Forum organised by the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) in conjuction with the Uganda National Information Technology Authority – Uganda (NITA-U) and the Internet Society Chapter Uganda is available for download here.

The report of the 5th Uganda Internet Governance Forum organised by the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) in conjuction with the Uganda National Information Technology Authority – Uganda (NITA-U) and the Internet Society Chapter Uganda is available for download here.

ICT4Democracy in East AFrica Workshop in Dar es Salaam

The ICT4Democracy East Africa Network – of which CIPESA is a member – is currently holding a two day workshop in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. This workshop aims to promote the Network’s activities with partners showcasing the progress of their work to improve democratisation in the region.

The ICT4Democracy East Africa Network – of which CIPESA is a member – is currently holding a two day workshop in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. This workshop aims to promote the Network’s activities with partners showcasing the progress of their work to improve democratisation in the region.

The event was officially opened by Eng. Dr. Zaipuna Yonah, the Director of ICT, Ministry of Science and Technology in Tanzania. In his opening address, Eng. Dr. Zaipuna thanked the government of Sweden through (SPIDER) The Swedish Program for ICT in Developing Regions and SIDA (Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency) for supporting the development of ICTs in the developing world and indicated that the work of the ICT4Democracy in East Africa network is already impacting the lives of citizens living in the region.

Eng. Dr. Zaipuna also highlighted the work the Tanzanian government was doing in developing ICT infrastructure within the country and extending it to neighbouring countries. He urged the members of the network to continue sharing the progress of their initiatives saying that “Accountability should not only be in what we read and write, democracy is more about translating the intentions into realities.”

To view the complete photo gallery of the ongoing workshop visit this link.

The presentations from the workshop will be uploaded at www.ict4democracy.org