By Kofi Yeboah|

There are many users of internet based platforms, like Facebook and Google, who are unaware of the existence of the terms and conditions that are available on the platform websites for users to familiarise themselves with and understand. The terms and conditions outline what is expected of both parties in agreement and also what both parties can and cannot do including with private data. Whose responsibility is it to popularise these often long policies to users?

This question was one of the most debated and discussed at the just ended Forum on Internet Freedom in Africa 2016 (FIFAfrica16) which was organised by the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA). Sharing of user data by internet based firms, either upon request by particular governments or other entities has become one of the most worrying factors for many internet users. Users of social media platforms do not entirely have control over who has access to their data, neither do they always have an understanding of the privacy policy associated with using these platforms.

As part of the panel discussion on transparency and accountability of intermediaries at#FIFAfrica16, Ebele Okobi, Head of Public Policy, Africa, Facebook, stated that “terms of service are the main mechanism used by companies to communicate with customers. Read them”. In other words, it is the responsibility of the user to read and understand what the terms of service say. However, most users do not read the terms of service “before clicking accept” and as pointed out by Anriette Esterhuysen of the Association for Progressive Communications (APC), firms hide behind that user ignorance to achieve their strategic goals at the detriment of user privacy.

Do Terms of Service Govern the Relationship?

“Terms of services do not govern the relationship between users and the company,” noted Ms. Okobi. She added that terms of service are the mechanism by which companies communicate with their users on the product. This implies that a firm can take an action that will affect a user with or without his/her permission.

What can be done?

Terms of services need to be in clear language and displayed boldly for users to read and understand. Internet-based firms should also consciously create awareness about the importance of reading the terms of services and also interpreting them to users. The firms should take the first step in explaining to users what the terms of services actually mean and what are they agreeing to for using the products. Terms of service should be simplified for users to understand the risks involved in signing up onto a platform and also outline how their data will be collected and used.

Meanwhile, users need to understand the rights they are giving up to internet-based firms when they check the “I agree” box on terms of service. On an ongoing basis, companies need to communicate with users to help understand why they need to collect their information and assure them the data being collected will be secured and not shared with third parties without their consent.

This article was first published at kofiyeboah.com on October 10, 2016.

Cyber Diplomacy with Africa: Lessons From the African Cybersecurity Convention

By Mailyn Fidler |

Two years ago, the African Union (AU) adopted its Convention on Cybersecurity and Personal Data Protection. The Convention seeks to improve how African states address cybercrime, data protection, e-commerce, and cybersecurity. However, only eight of the AU’s fifty-four members have signed the Convention, with none ratifying it. Despite this currently limited uptake, the Convention, and how the AU produced it, signals that African states value political autonomy and independence when developing cyber policy. The U.S. government should keep this in mind as it reaches out to AU member states in promoting cyber norms and capacity building efforts.

Development of the Convention

The AU’s development of the Convention reflects a desire of African states to have autonomy over their response to cyberspace challenges. The AU chose to develop its own Convention instead of promoting African participation in existing cyber treaties, most notably the Council of Europe’s Budapest Convention on Cybercrime (2001). Only one African state, South Africa, participated in the Budapest Convention negotiations, and, even then, had to ask to be included. The Council of Europe approved three other African country requests to accede, a low rate compared to other regions in the global south, and only one African state has ratified it. South Africa has refused to ratify the Budapest Convention because of sovereignty concerns.

Instead, the AU began work on its own approach in 2007. By this time, African states had already started to act as a bloc in international cyber negotiations. For instance, African countries advocated for more equitable access to the Internet and participation in Internet governance during the 2003 and 2005 World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) – a stance that challenged prevailing Western views.

Read the full article here.

Analysis of the Relationship Between Online Information Controls and Elections in Zambia

By Arthur Gwagwa |

The defining era in Zambia’s current rise in online political and civic activism can be traced back to the period between 2011 and 2013. This is when the late President Sata embraced social media as part of his political and public diplomacy strategy. As the country now prepares for the August 2016 General Elections, government, its agencies, such as the Election Ccommission of Zambia (ECZ), the opposition and civil society are all immersed in social media.

As the country’s August 2016 polls draw nearer, government has recently increased its presence on social media to abet and encourage horizontal flows of information. This is in contrast to vertical flows, where information generated by societal actors is gathered by the government through usage of a range of methods, ranging from “responsiveness” on social media to media monitoring.

This paper explores reports of information controls and filtering of the ruling regime, whose leader, Edgar Lungu, strives to balance the dictates of political survival and his reputation as a lawyer who has previously defended press freedoms. The paper analyses past and current key political events that implicate the relationship between internet-based information controls and elections in Zambia. Finally, the paper extrapolates likely scenarios in the build up to the 2016 General Elections and Constitution Bill of Rights Referendum to be held on 11 August 2016.

Read the full report here.

Pushing Back Against Internet Shutdowns

By Marylin Vernon |

Advancing human rights for the 3.2 billion users of the internet, of which two billion are from developing countries, needs a robust and systematic approach to ensure that the rights individuals enjoy offline are also applicable online. Indeed, debate on protecting online freedoms has taken centre stage as incidents of blockage of access of the internet and related platforms have increased in several countries around the world.

Reports of a recent internet shutdown in Algeria bring to 16, the number of countries affected by shutdowns documented in the first half of 2016. As many as 15 shutdowns were documented in 2015. Of the documented incidents, six occurred in African countries in 2015 and four have been reported this year.

In 2015, internet shutdowns occurred in Algeria, Burundi, Congo Brazzaville, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Niger, and Togo. Before last month’s shutdown in Algeria, Chad, Uganda, and Ethiopia had earlier this year experienced shutdowns. Meanwhile, other governments, such as Ghana, are considering a social media black-out during the November 2016 election period purportedly to curb abuse of social media.

Ahead of the presidential inauguration last May, Uganda’s Communications Commission (UCC) issued a directive to all telecom providers to shut down social media platforms citing security concerns. This directive saw major telcos, such as MTN Uganda, issuing statements of compliance, citing licensing regulations that dictate mandatory cooperation with government in the event of an emergency or on issues related to national security. Uganda is currently ranked as not free in the Freedom in the World report 2016.

Chad’s decision to shut down the internet and block SMS messaging for several days during the April 2016 election period raised concerns and criticism from the international community and political opposition, with many doubting the credibility of the electoral outcome that extended the 26-year rule of President Idriss Déby. The situation in Chad was reminiscent of the election periods in Congo and Ethiopia, in which social media and other file sharing platforms were blocked ahead of voting, or during civil and political unrest.

There has been widespread condemnation of these unwarranted actions that are often taken in the name of protecting national security, but which have far-reaching consequences for freedom of expression, privacy and the free flow of information. During RightsCon 2016, which took place in San Francisco, United States on March 30 to April 1, AccessNow launched the #KeepItOn campaign to push back on the use of internet shutdowns by governments worldwide. The campaign kicked off with crowdsourcing a definition of an internet shutdown based on numerous suggestions made by experts from Africa, Latin America, Europe, North America, and Asia.

The current working definition of an internet shutdown is: “An intentional disruption of internet or electronic communications, rendering them inaccessible or effectively unusable, for a specific population or within a location, often to exert control over the flow of information.”

Meanwhile, in order to mitigate the effects of internet shutdowns and advance user privacy and security as well as the work of human rights defenders and activists, AccessNow launched a digital security helpline. The Helpline comprises of a team of technologists with a dedicated 24 hour hotline to aid civil society actors with on-call access to rapid response and follow-up for digital security issues, support for securing technical infrastructure, and preventative advice ahead of anticipated attacks (e.g. the lead up to an election).

Globally, many states are party to international human rights treaties such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) which reinforces many of the rights articulated in the UDHR, and the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights (ACHPR). However, some governments are yet to enact national laws that guarantee data protection and privacy, as well as transparency and accountability in surveillance practices and censorship.

Now more than ever, understanding by state and non-state actors of the obligation to uphold online freedoms is crucial. Efforts in capacity building for digital safety, awareness raising and advocacy require continued documentation of shutdowns, gathering and disseminating information and contributing to the ongoing global public discourse.

Join a global coalition of organisations in the #KeepItOn campaign by a taking a pledge of action, by telling people about the campaign and sharing relevant information.

Ugandan Artists, Journalists Decry Declining Freedom of Expression

By Ashnah Kalemera |

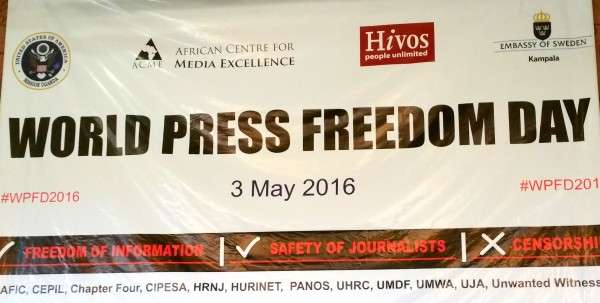

As the world celebrated World Press Freedom Day (WPFD), the media and artists in Uganda spoke in unison about declining levels of freedom of expression in the country. Media practitioners challenged the constitutionality of Uganda’s 20-year press law and the impartiality of the national media ombudsman. Meanwhile, artists cited a growing trend of self-censorship among their community due to a fear of backlash from the state.

Musician Robert Kyagulanyi a.ka. Bobi Wine, an outspoken proponent for free expression, explained that communicating social issues through music was both “exciting and annoying” to audiences. Kyagulanyi said over the years he had experienced backlashes for making songs critical of state authorities. In 2012, the Uganda Communications Commission (UCC) allegedly banned radio airplay of Kyagulanyi’s song which criticised the Kampala City Council Authority Executive Director. Earlier this year, there were reports that UCC had once again banned another of Kyagulanyi’s songs – this time with content related to elections. It could not be verified whether the commission indeed banned radio stations from playing the song titled Ddembe. The singer stated that state-owned media had on numerous occasions declined to play some of his music that criticised the government.

“Much as censorship does not come direct, we must acknowledge that it exists for artists,” said Kyagulanyi at an event in Kampala to mark WPFD.

Kyagulanyi’s sentiments were echoed by another prominent Ugandan musician, Irene Ntale, who said she and many others often found themselves “limited” to making commercial music that is “easily saleable and sustains livelihoods” and refraining from critical songs.

“If I want to sing about the political situation in Uganda, I am afraid. Am I going to get into trouble?” said Ntale. She added that other forms of her expression, such as the attire she wears while performing, were also under threat from the Anti-Pornography Act (2014). The Act outlaws the publication and consumption of real or simulated sexual activities, or representation of sexual parts of a person.

Uganda, like many other African countries, lacks a comprehensive legal framework to promote creative, artistic and cultural expression. The country has a national Culture Policy (2006) and ratified to the 2005 UNESCO Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expression in 2015. However, protections are not guaranteed and there have been reports of abuse and infringements on artists’ rights when their work challenged political, religious and social norms. In 2012, screening of a Ugandan play titled “State of the Nation” was cancelled by the Media Council because of its subject matter of corruption and poor governance, while in 2013, Daniel Cecil, a British theatre producer, was deported from Uganda following work on a play that had a gay character.

Both Kyagulanyi and Ntale called for the media to offer more support to the creative sector when artists’ freedom of expression is under attack. However, the media itself is experiencing rising attacks, and the Press and Journalist Act (1995), which regulates the media, is “antithetic to media freedom and democracy”, according to Makerere University journalism lecturer Adolf Mbaine . He said the Media Council established under this law had led to “direct government control over what journalists can and can’t do”. This had contributed to an engrained fear among journalists and other actors on how to exercise their freedom of expression.

Mbaine also contended that freedom of the media was not a “professional right” and should therefore not be regulated. “Media belongs to everyone including the public through media,” he said.

Meanwhile, Peter Magellah of Chapter Four pointed out that there were no provisions in Uganda’s Press and Journalists Act relating to online publications and new media platforms. Under the Uganda Communications Act (2013), the Uganda Communications Commission (UCC) has the mandate to regulate telecommunications services including broadcast and online media. In February 2016, the UCC issued a statement calling for “professional and responsible behaviour among broadcasters and users of social media” during elections that were held the same month.

The chairman of the Uganda Law Society, Francis Gimara, called for more “legal challenges” to the 1995 law as well as other matters related to the rule of law with an impact on freedom of expression in Uganda. Other recommendations made included:

- Industry-led regulation of journalists with active stakeholder participation. This would, among others, advance increased accountability of the media on issues of ethical conduct.

- Media should become activists of press freedom and freedom of expression.

- Media should cover more societal issues that artists portray instead of tending to focus on the lifestyles of the artists.

- Increased documentation and reporting on violations of creative and artistic expression akin to documentation of violation of freedom of expression for journalists and activists.

The WPFD celebration was organised by the African Centre for Media Excellence (ACME) jointly with other partners. The dialogue explored the right to freedom of expression and the right to information through online and offline media as fundamental pillars of democracy.

Follow the online conversation on WPFD with the hashtags: #WPFD16 and #ThisIsFreedom