By CIPESA Writer |

In many African countries, the regulation of the use of encryption considers “national security” as the predominant concern and gives limited consideration to other areas that would benefit from the use of secure tools and technologies. Accordingly, many countries in the region are saddled with laws that unreasonably limit the use of encryption by individuals and businesses, which in turn undermine digital rights and the digital economy.

Encryption technologies enable users of digital technologies, including the internet and messaging services, to protect the confidentiality of their data and communications from unwarranted interception, observation and intrusion. Such protections are essential for businesses to thrive and be resilient, in addition to being key considerations by their customers. Those protections are crucial for individuals to enjoy their rights to privacy, free expression, and public participation.

As the world marks the Data Privacy Day on January 28, it is imperative that reflection is drawn onto Africa’s performance in regards to the role that encryption regulation plays in human rights protection online and promoting the digital economy.

The Digital Economy

The digital economy in Africa is steadily growing and contributes significantly to countries’ Gross Domestic Product (GDP), besides being a notable direct employer. As of the end of 2021, around 33% of individuals in Africa used the internet, while there were eight mobile cellular telephones for every 10 individuals in the region, according to the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) figures.

Across the continent there has been significant growth in the penetration, access, and usage of Information and Communications Technologies (ICT). At the same time, the use of ICT is taking centre stage in education, health, economic, and governance sectors. It is also driving financial inclusion, with fintechs proliferating at high speed. In 2020, mobile technologies and services generated more than USD 130 billion of economic value added (or 8% of GDP) in Sub-Saharan Africa, according to the GSMA. In that year, the value of transactions on mobile money platforms in the region reached USD 490 billion.

Many governments are undertaking digitalisation programmes and have prioritised the integration of technology into more sectors to drive economic and social transformation. However, the growing rate of digital transformation in Africa is creating new cybersecurity threats which must be addressed to unlock new pathways for technology-enabled economic growth, innovation, job creation and service delivery.

Regulation that facilitates the use of strong encryption by individuals and companies as opposed to limitation and prohibition of use is one way of nipping those risks in the bud and building trust and confidence to embrace and participate in the digital economy.

Various countries’ laws require registration and licensing of encryption service providers, and regulators have extensive powers to prohibit the use of some encryption technologies. Moreover, offering encryption services without licenses attracts penalties, as does failure to hand over secret encryption codes to state authorities, or using prohibited encryption tools. How African Countries Undermine Use of Encryption.

⁉️What's the relationship between #DataPrivacy & #Encryption? How does it support #InternetFreedomAfrica #DigitalRights? Watch the 📽️⁉️

See this #policybrief on How African Governments Undermine the Use of Encryption👉🏾https://t.co/wHcxgnZbwC#DataPrivacyWeek #DataPrivacyDay pic.twitter.com/WeSw4BBpqy

— CIPESA (@cipesaug) January 27, 2022

In 2021, research by the Internet Society (ISOC) showed that laws that undermine encryption can significantly harm the national economy, with the single biggest source of adverse economic effects being the indirect threat that such laws pose for trust in the internet and digital services. This reduced trust in data security depresses aggregate demand across the digital economy and induces firms to incur higher costs in attempts to build trust in their services.

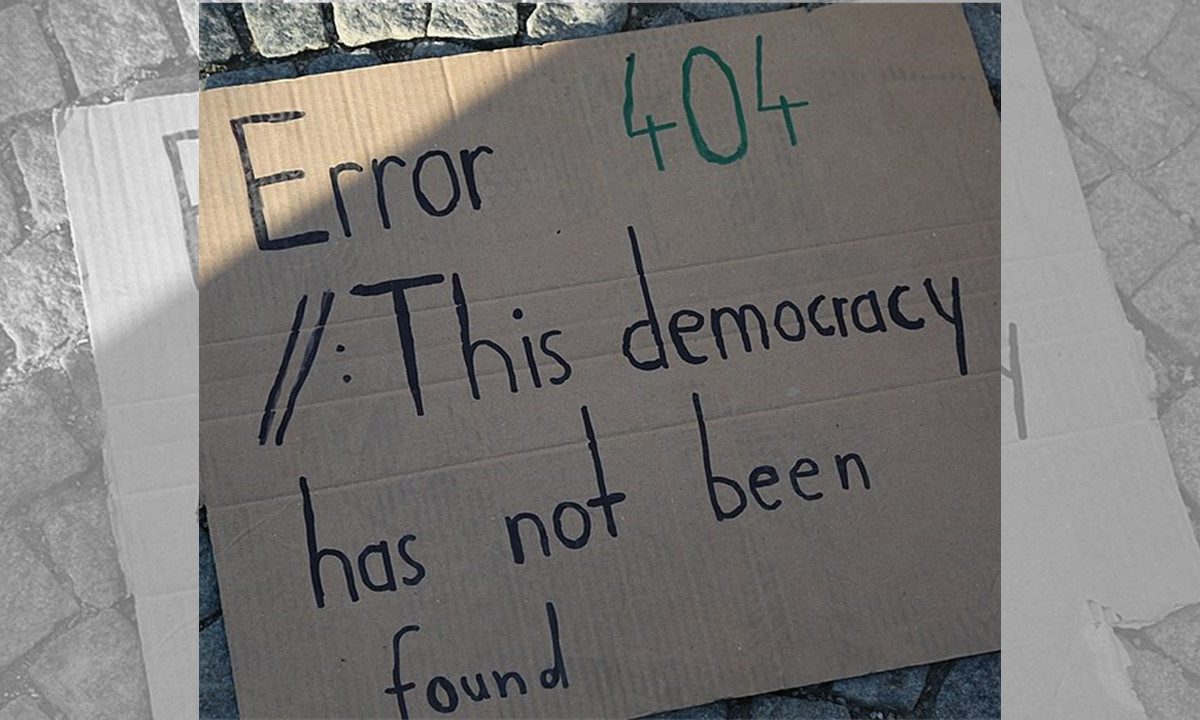

Digital Rights

Compelled assistance by service providers as part of interception of communications, including the requirement to decrypt encrypted data and communications or disclose encryption keys gives governments and their agencies unfettered access to personal data, undermining citizens’ right to privacy and various other digital rights. Countries including Benin, Gabon, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and Zimbabwe prohibit service providers from providing any communications services that cannot be lawfully intercepted.

Such prohibitive regulations undermine digital rights in similar ways to laws on surveillance, which impose undue liability on intermediaries, and fail to provide for strong judicial oversight over surveillance operations. Meanwhile, data localisation requirements in some countries further grant authorities easier access to data for decryption and surveillance purposes with or without compelled assistance, “as they would not need to go through foreign countries’ or intermediaries’ data management protocols to access this data”, as highlighted by recent CIPESA research. Combined with mandatory SIM card registration and growing biometric databases, they thus contribute to the regressive situation for online freedom in a region fraught with human rights abuses and violations.

Securitising Encryption

Various countries regulate the use of encryption with national security as the sole key consideration. In Ivory Coast, the Telecommunications Regulatory Authority (ARTCI) is tasked to ensure that no service provider employs encryption that is contrary to public order or which undermines the interests of national defence, internal or external security of the state. Similarly, in the Central African Republic, the Electronic Communications Law of 2018 empowers the security minister to approve encryption services “based on the need to preserve the internal and external security of the state and national defence.”

Moroccan legislation restricts the import and use of encryption “to prevent its use for illegal purposes, and to protect the interests of national defence and the internal or external security of the State.” In that spirit, in 2015, the responsibility for authorising and monitoring encryption in Morocco was moved from the civilian National Telecommunications Regulatory Agency (ANRT) to the military’s General Directorate for the Security of Information Systems (DGSSI).

In Algeria, the acquisition and use of encryption by individuals and organisations must be authorised by the Regulatory Authority of Post and Electronic Communications (ARPCE) after approval by the Ministry of Defence and the Ministry of the Interior. Further, Algerian law requires that the type and nature of the equipment that will be used, list of cryptography algorithms, the size of the encryption keys, the type of virtual private network (VPN) used, the authentication methods, and the Public IP address, be provided to the regulator while applying for authorisation.

Many other countries require registration, while also requiring service providers to disclose the technical characteristics of the cryptology means, and the source code of the software used. Concerningly, some countries (including Benin, Gabon, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and Zimbabwe) prohibit service providers from providing any communications services that cannot be lawfully intercepted.

Overall, these limitations to the use of encryption go against Principle 40(3) of the Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information in Africa, which provides that “States shall not adopt laws or other measures prohibiting or weakening encryption, including backdoors, key escrows, and data localisation requirements unless such measures are justifiable and compatible with international human rights law and standards.”

Ultimately, all laws that place undue restrictions on the use of encryption tools should be repealed.

To promote the use of encryption in the region, it is imperative to desist from the current trends towards securitisation of encryption regulation. While governments often require surveillance to curb crime, laws should not outrightly prohibit or criminalise the use of encryption technologies. Rather, they should be supportive of legitimate state interests, which also robustly protect digital rights and support growth of the digital economy.