By FIFAfrica |

The Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) is pleased to announce that the 2025 edition of the Forum on Internet Freedom in Africa (FIFAfrica25) will be co-hosted in partnership with the Namibian Ministry of Information and Communication Technology (MICT) and the Namibia Internet Governance Forum (NamIGF).

Set to take place in Windhoek, Namibia, from September 25–27, 2025, this year’s Forum will serve as yet another notch in FIFAfrica’s 12-year history of assembling digital rights defenders, policymakers, technologists, academics, regulators, journalists, and the donor community, who all have the shared vision of advancing internet freedom in Africa.

With its strong commitments to democratic governance, press freedom, and inclusive digital development, Namibia offers fertile ground for rich dialogues on the future of internet freedom in Africa. The country holds a powerful legacy in the global media and information landscape, being the birthplace of the 1991 Windhoek Declaration on promoting independent and pluralistic media. In a digital age where new challenges are emerging – from information integrity and Artificial Intelligence (AI) governance to connectivity gaps and platform accountability – hosting FIFAfrica in Namibia marks a key moment for the movement toward trusted information as a public good, including in the digital age.

“Through the Ministry of Information and Communication Technology, Namibia is proud to co-host FIFAfrica25 as a demonstration of our commitment to advancing technology for inclusive social and economic development. This Forum comes at a critical moment for Africa’s digital future, and we welcome the opportunity to engage with diverse voices from across the continent and beyond in shaping a rights-respecting, secure, and innovative digital landscape,” Minister of Information and Communication Technology (ICT), Emma Inamutila Theofelus

This sentiment is shared by the NamIGF Chairperson, Albertine Shipena. “We are honoured to co-host the FIFAfrica25 here in Namibia. This partnership with MICT and CIPESA marks a significant step in advancing digital rights, open governance, and meaningful multistakeholder engagement across the continent. As the NamIGF, we are proud to contribute to shaping a more inclusive and secure internet ecosystem, while spotlighting Namibia’s growing role in regional and global digital conversations.”

The NamIGF was established in September 2017, through a Cabinet decision, as a multistakeholder platform that facilitates public policy discussion on issues pertaining to the internet in Namibia.

Dr. Wairagala Wakabi, the CIPESA Executive Director, noted that FIFAfrica25 presents a timely opportunity to advance progressive digital policy agendas that uphold fundamental rights and promote digital democracy in Africa. “As global debates on internet governance, data sovereignty, and platform accountability intensify, it is essential that Africans inform and shape the frameworks that govern our digital spaces. We are honoured to partner with the Namibian government and NamIGF to convene this critical conversation on the continent,” he said.

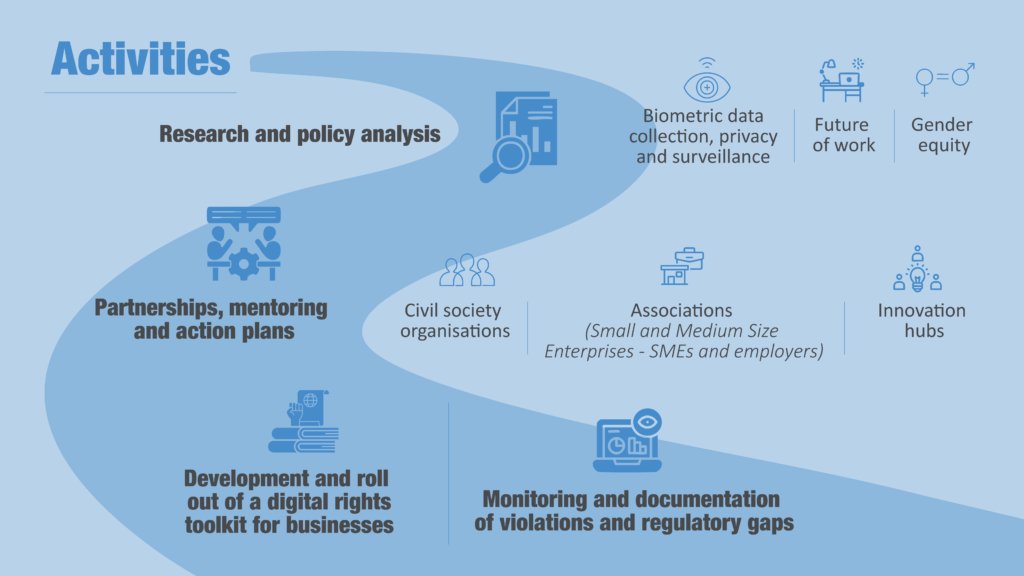

Since its inception in 2014, FIFAfrica has grown to become the continent’s leading assembly of actors instrumental in shaping conversations and actions at the intersection of technology with democracy, society and the economy. It has become the stage for concerted efforts to advance digital rights and digital inclusion. These issues, and new emerging themes such as mental health, climate and the environment, and the content economy, will take centre stage at FIFAfrica25, which will feature a mix of plenaries, workshops, exhibitions, and a series of pre-events.

Meanwhile, FIFAfrica will also recognise the International Day for Universal Access to Information (IDUAI), celebrated annually on September 28. The commemoration serves to underscore the fundamental role of access to information in empowering individuals, supporting informed decision-making, fostering innovation, and advancing inclusive and sustainable development – tenets which resonate with the Forum. This year’s celebration is themed, “Ensuring Access to Environmental Information in the Digital Age”.

At the heart of the Forum is a Community of Allies that have, over the years, stood alongside CIPESA in its pursuit of effective and inclusive digital governance in Africa.

Feedback on Session Proposals and Travel Support Applications

All successful session proposals and travel support applicants have been contacted directly. See the list of successful sessions here. Thank you for your patience and for contributing to what promises to be an exciting FIFAfrica25.

Prepare for FIFAfrica25: Travel and Logistics

Everything you need to plan your attendance at the Forum can be found here – visit this page for key logistical details and tips to help you make the most of your experience!