Announcement |

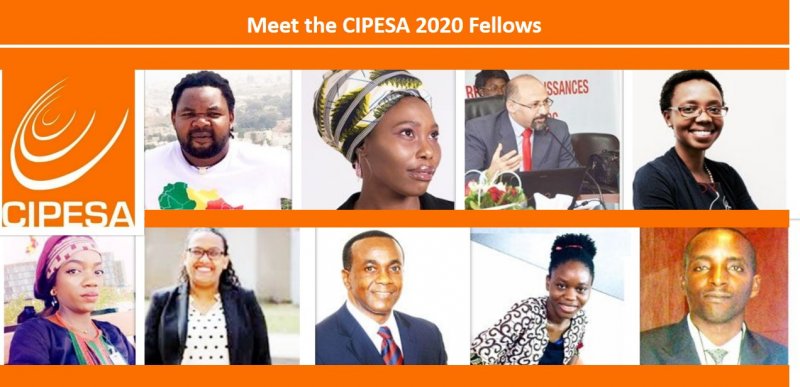

The Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) is pleased to announce the nine recipients of its 2020 fellowship awards. Introduced in 2017, CIPESA’s fellowship programme aims to increase the quality, diversity and regularity of research and media reporting on ICT, democracy, and human rights in Sub-Saharan Africa.

The fellowship programme cultivates links between the academic community and practitioners in the ICT field for mutual research, learning, and knowledge exchange, so as to create the next generation of ICT for democracy and ICT for human rights champions and researchers.

In the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, the nine fellows will primarily focus their energies on researching Covid-19 related censorship and surveillance practices and policy/regulatory responses by governments and private actors; and documenting trends and developments in technology for public good policy and practice.

Meet the fellows:

Astou Diouf – Senegal – Astou is a lawyer with undergraduate and postgraduate qualifications from Faculté des Sciences Juridiques et Politiques (FSJP), l’Université Cheik Anta DIOP de Dakar, with extensive experience in business litigation, cybercrime, and cybersecurity. She will research the role of internet intermediaries and service providers in the fight against Covid-19 in Senegal, including on issues such as facilitating increased access to the internet, privacy and personal data infringements, and content regulation.

Astou Diouf – Senegal – Astou is a lawyer with undergraduate and postgraduate qualifications from Faculté des Sciences Juridiques et Politiques (FSJP), l’Université Cheik Anta DIOP de Dakar, with extensive experience in business litigation, cybercrime, and cybersecurity. She will research the role of internet intermediaries and service providers in the fight against Covid-19 in Senegal, including on issues such as facilitating increased access to the internet, privacy and personal data infringements, and content regulation.

Hopeton S. Dunn, PhD – Botswana – Hopeton is a Professor of Media and Communications at University of Botswana. He is also a non-resident Senior Research Associate at the School of Communication, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. He is the former Director of the Caribbean School of Media and Communication (CARIMAC), University of the West Indies (UWI), Jamaica, where he also headed the Mona ICT Policy Centre (MICT). He is interested in communications policy reform, digital literacy and inclusion, effective internet access and equity, especially as they relate to people in the Global South. His work spans media regulation, technology policy-making, and new theoretical constructs for development.

Hopeton S. Dunn, PhD – Botswana – Hopeton is a Professor of Media and Communications at University of Botswana. He is also a non-resident Senior Research Associate at the School of Communication, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. He is the former Director of the Caribbean School of Media and Communication (CARIMAC), University of the West Indies (UWI), Jamaica, where he also headed the Mona ICT Policy Centre (MICT). He is interested in communications policy reform, digital literacy and inclusion, effective internet access and equity, especially as they relate to people in the Global South. His work spans media regulation, technology policy-making, and new theoretical constructs for development.

With a focus on Botswana and South Africa, Prof. Dunn will study the status of broadcast and online media regulation; technology and learning during the Covid-19 pandemic; and internet access and inclusion.

Afi Edoh – Togo – Togolese technology enthusiast Afi will study digital transformation and the digital economy in Ivory Coast, Ghana, and Togo during the Covid-19 pandemic, to determine value and innovation opportunities as well as challenges. She is a member of the organising committee of the Internet Governance Forum for Youth in West Africa and has also served on the United Nations Internet Governance Multi-Stakeholder Advisory Group (MAG). She holds a Masters and Bachelors in Information Technology from Sikkim Manipal University.

Afi Edoh – Togo – Togolese technology enthusiast Afi will study digital transformation and the digital economy in Ivory Coast, Ghana, and Togo during the Covid-19 pandemic, to determine value and innovation opportunities as well as challenges. She is a member of the organising committee of the Internet Governance Forum for Youth in West Africa and has also served on the United Nations Internet Governance Multi-Stakeholder Advisory Group (MAG). She holds a Masters and Bachelors in Information Technology from Sikkim Manipal University.

Mohamed Farahat – Egypt – Mohamed is an Egyptian human rights lawyer, specialised in refugees and migration. He is a member of the Steering Committee of Internet Rights and Principles Coalition (IRPC), a member of the Multi-Stakeholder Advisory Group (MAG) of the North Africa Internet Governance Forum, and the National Coordinator of the African Civil Society on Information Society (ACSIS) Egypt chapter. Since 2014, he has worked with the Egyptian Foundation for Refugees Rights (EFRR). He holds a degree in Law from Cairo University, and post-graduate diplomas in International Negotiation; Human Rights and Civil Society; African Studies; and International Law. Currently, he is a Master Degree researcher in the Faculty of African Studies – Cairo University.

Mohamed Farahat – Egypt – Mohamed is an Egyptian human rights lawyer, specialised in refugees and migration. He is a member of the Steering Committee of Internet Rights and Principles Coalition (IRPC), a member of the Multi-Stakeholder Advisory Group (MAG) of the North Africa Internet Governance Forum, and the National Coordinator of the African Civil Society on Information Society (ACSIS) Egypt chapter. Since 2014, he has worked with the Egyptian Foundation for Refugees Rights (EFRR). He holds a degree in Law from Cairo University, and post-graduate diplomas in International Negotiation; Human Rights and Civil Society; African Studies; and International Law. Currently, he is a Master Degree researcher in the Faculty of African Studies – Cairo University.

As part of the fellowship, Mohamed will document inclusion of refugees in the technology-based responses to the Covid-19 pandemic in Egypt; and the role of the judiciary in the internet freedom landscape in North Africa.

Tusi Fokane – South Africa – Tusi, the former Executive Director of the Freedom of Expression Institute (FXI), will study the availability and use of digital technologies to combat the spread of Covid-19 in South Africa, with a focus on the criminalisation of misinformation, and obligations on service providers to remove fake news from their platforms. Furthermore, she will study the country’s readiness for electronic voting to comply with social distancing and other movement restrictions during the upcoming local government elections. Tusi is a co-founder and member of the Steering Committee of Re-Create, a coalition of South African creators who advocate for fair and balanced provisions in the ongoing copyright amendment process. She holds a Masters in Management degree in Public Policy from Wits University. Her particular interests are freedom of expression, technology, and human rights.

Tusi Fokane – South Africa – Tusi, the former Executive Director of the Freedom of Expression Institute (FXI), will study the availability and use of digital technologies to combat the spread of Covid-19 in South Africa, with a focus on the criminalisation of misinformation, and obligations on service providers to remove fake news from their platforms. Furthermore, she will study the country’s readiness for electronic voting to comply with social distancing and other movement restrictions during the upcoming local government elections. Tusi is a co-founder and member of the Steering Committee of Re-Create, a coalition of South African creators who advocate for fair and balanced provisions in the ongoing copyright amendment process. She holds a Masters in Management degree in Public Policy from Wits University. Her particular interests are freedom of expression, technology, and human rights.

Jimmy Kainja – Malawi – Jimmy Kainja is a lecturer in media, communication, and cultural studies at University of Malawi, Chancellor College. His main areas of academic and research interest are communication policy and regulation, journalism, new media, (mis)information and disinformation, freedom of expression, and the intersection between media and democracy. Kainja has been a blogger since 2007 and is a founding member of Africa Blogging, which he co-edited between 2015 and 2019. In addition, Kainja has written for a number of reputable international media organisations including the BBC, The Guardian, Aljazeera, and New African. Locally he is a regular contributor of analytical articles to Nation Publications Limited newspapers.

Jimmy Kainja – Malawi – Jimmy Kainja is a lecturer in media, communication, and cultural studies at University of Malawi, Chancellor College. His main areas of academic and research interest are communication policy and regulation, journalism, new media, (mis)information and disinformation, freedom of expression, and the intersection between media and democracy. Kainja has been a blogger since 2007 and is a founding member of Africa Blogging, which he co-edited between 2015 and 2019. In addition, Kainja has written for a number of reputable international media organisations including the BBC, The Guardian, Aljazeera, and New African. Locally he is a regular contributor of analytical articles to Nation Publications Limited newspapers.

In the context of the February 3, 2020 Constitutional Court nullification of the presidential elections and scheduled fresh polls in June 2020, and in parallel to the Covid-19 pandemic, Kainja will study hate speech and misinformation, data protection, and access to information.

Jean Paul Nkurunziza – Burundi – Jean Paul, a psychology and education sciences graduate of the University of Burundi, has been involved in digital rights policy and internet governance with the DiploFoundation and Internet Society since 2007. In 2010, he was awarded a fellowship at the United Nations Internet Governance Forum Secretariat. His CIPESA fellowship will focus on the political tensions in Burundi, including the recent internet disruption during elections; and ICT sector reforms by the new government, related to cybersecurity, privacy, and data protection.

Jean Paul Nkurunziza – Burundi – Jean Paul, a psychology and education sciences graduate of the University of Burundi, has been involved in digital rights policy and internet governance with the DiploFoundation and Internet Society since 2007. In 2010, he was awarded a fellowship at the United Nations Internet Governance Forum Secretariat. His CIPESA fellowship will focus on the political tensions in Burundi, including the recent internet disruption during elections; and ICT sector reforms by the new government, related to cybersecurity, privacy, and data protection.

Dunia Tegegn – Ethiopia – Dunia is a legal consultant, who has previously worked as an Almami Cyllah Fellow with Amnesty International (United States) and as a Human Rights Officer at the East Africa Regional Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. Dunia also worked as a Program Officer on Ending Violence against Women and Girls at UN Women Ethiopia, and on child protection issues with UNICEF Ethiopia. She holds a Master of Laws in National Security from Georgetown University Law Center and a Master of Arts in Human Rights from Addis Ababa University. Dunia is the first Africa Fellow for Georgetown’s LAWA program to earn a Master of Laws in National Security. She earned her bachelor degree in law from Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia. Dunia is a member of the Pan African Lawyers Union (PALU), the Ethiopian Bar Association, and the Ethiopian American Bar Association.

Dunia Tegegn – Ethiopia – Dunia is a legal consultant, who has previously worked as an Almami Cyllah Fellow with Amnesty International (United States) and as a Human Rights Officer at the East Africa Regional Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. Dunia also worked as a Program Officer on Ending Violence against Women and Girls at UN Women Ethiopia, and on child protection issues with UNICEF Ethiopia. She holds a Master of Laws in National Security from Georgetown University Law Center and a Master of Arts in Human Rights from Addis Ababa University. Dunia is the first Africa Fellow for Georgetown’s LAWA program to earn a Master of Laws in National Security. She earned her bachelor degree in law from Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia. Dunia is a member of the Pan African Lawyers Union (PALU), the Ethiopian Bar Association, and the Ethiopian American Bar Association.

For her fellowship, she will study the role of the internet and access to information during 2020 elections in Egypt, Ethiopia, and Somalia.

Melissa Zisengwe – South Africa – Melissa is a Program Project Officer with the Civic Tech Innovation Network at Wits Governance School, based in South Africa. She holds an honours degree in Journalism and Media Studies and a Bachelor of Arts in English Language and Linguistics and Journalism and Media Studies from Rhodes University. Her work at the Civic Tech Innovation Network and Jamlab (also at Wits) focuses on digital innovation in Africa, including digital journalism and media, and promoting the growth and development of appropriate and effective uses of digital technologies in connecting government and citizens, in public participation, in transparency and accountability, and in delivering public services. In 2019 she was part of the Index on Censorship Youth Advisory Board – a project by Index on Censorship aimed at engaging with young people aged 16-25 from around the world and gathering their views on freedom of expression issues.

Melissa Zisengwe – South Africa – Melissa is a Program Project Officer with the Civic Tech Innovation Network at Wits Governance School, based in South Africa. She holds an honours degree in Journalism and Media Studies and a Bachelor of Arts in English Language and Linguistics and Journalism and Media Studies from Rhodes University. Her work at the Civic Tech Innovation Network and Jamlab (also at Wits) focuses on digital innovation in Africa, including digital journalism and media, and promoting the growth and development of appropriate and effective uses of digital technologies in connecting government and citizens, in public participation, in transparency and accountability, and in delivering public services. In 2019 she was part of the Index on Censorship Youth Advisory Board – a project by Index on Censorship aimed at engaging with young people aged 16-25 from around the world and gathering their views on freedom of expression issues.

Inspired by the African Civic Tech database and the South Africa Cities Network Call for Local Covid-19 Data Responses, which is compiling an open evidence mapping of the use of open government data to address the Covid-19 response in South Africa’s cities and provinces, Melissa will study the use and adoption of civic tech during Covid-19 in select African countries. The research will pay close attention to Covid-19 civic tech and data responses related (but not limited to): Epidemiological info — a disease spread maps, statistics, dashboards; Disaster response information; Health and risk information; Services — food relief, disruptions, etc.; Information, guidelines, resource tools — for businesses, communities, citizens; Research and advocacy; and Enhancing public communication and engagement and action.

Look out for the fellows’ outputs including blogs, policy briefs, and research reports on CIPESA’s online platforms in the coming months.

Astou Diouf – Senegal –

Astou Diouf – Senegal –  Hopeton S. Dunn, PhD – Botswana –

Hopeton S. Dunn, PhD – Botswana –  Afi Edoh – Togo –

Afi Edoh – Togo –  Mohamed Farahat – Egypt –

Mohamed Farahat – Egypt –  Tusi Fokane – South Africa –

Tusi Fokane – South Africa –  Jimmy Kainja – Malawi –

Jimmy Kainja – Malawi –  Jean Paul Nkurunziza – Burundi –

Jean Paul Nkurunziza – Burundi –  Dunia Tegegn – Ethiopia –

Dunia Tegegn – Ethiopia –  Melissa Zisengwe – South Africa –

Melissa Zisengwe – South Africa –