FIFAfrica19 |

Over the last six months, the Global Network Initiative (GNI) has been convening diverse stakeholders from sub-Saharan Africa to discuss pressing freedom of expression and privacy issues in the region. Research and consultations conducted by the GNI to-date indicate that government-enabled surveillance and network disruptions are of particular concern across multiple stakeholder groups, as well as other issues like social media taxes and data protection. Through these discussions, participants representing companies, civil society, and academia, among others, have exchanged important insights into these issues and identified ways multi-stakeholder efforts could advance shared aims.

At the upcoming Forum on Internet Freedom in Africa 2019 (FIFAfrica19), GNI will convene a session to continue the conversation about pressing freedom of expression and privacy issues in sub-Saharan Africa. The aim is for the pan-African assembly of participants to share updates and insights into pressing policy issues as well as collectively identify areas for possible collaborative advocacy between companies and civil society, such as through the development of shared statements or the identification of areas that need more research.

This session will be held on Wednesday September 25 under Chatham House rules and is open to attendees of FIFAfrica19. Please register in advance.

The consultations will extend to a panel taking place on September 26, also convened by GNI, titled “Disrupting Development: How Internet Shutdowns Impede the Sustainable Development Goals”. Speakers on this panel will demonstrate how open and unrestricted access to the internet facilitates achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). They will also discuss the consequences of disruptions for the achievement of SDGs, using recent examples of network disruptions in Africa to highlight these effects, and how governments can pursue the SDGs while respecting human rights. As an outcome of this session, attendees will understand the role of the internet in achieving the SDGs and will be equipped with ways to analyse how network disruptions impact their country’s realisation of the goals.

Panellists: Zama Ndege Godden, Blacked Out, Cameroon | Alp Toker, NetBlocks, Turkey | Berhan Taye, AccessNow, Ethiopia

Moderator: Jason Pielemeier, GNI

The GNI is a global multistakeholder network, composed of leading ICT companies, civil society organizations, academics, and investors. GNI’s mission is to protect and advance freedom of expression and privacy in the ICT industry by setting a global standard for responsible company decision making and by being a leading voice for freedom of expression and privacy rights.

Overview of Cameroon’s Digital Landscape

By Simone Toussi |

The Information and Communications Technology (ICT) sector in Cameroon has evolved considerably since 2010, despite the persistence of the digital divide and affronts to freedom of expression online. The country’s digital landscape was boosted by the launch in May 2016 of the National ICT Strategic Plan 2020, which recognised the digital economy as a driver for development. The country has registered increased investments in telecommunication and ICT infrastructure, including extension of the national optical fibre backbone to about 12,000 km, connecting 209 of the country’s 360 sub-divisions, and neighbouring countries such as Chad, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, the Central African Republic and Nigeria.

By 2018, the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications reported that mobile phone subscribers stood at 18.8 million representing a penetration rate of 83%, while internet penetration was 35%. There are four big telecommunications service providers in Cameroon – MTN, Orange, Viettel and the state-owned CAMTEL. With 48% of the mobile market share or 8.7 million subscribers, MTN is the leading service provider, according to its report for the first quarter of 2019.

Over the years, Cameroon has scored some improvements in ICT development and affordability. For instance, on the ICT Development Index (IDI) of the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), its value improved from 1.54 in 2010 to 2.38 in 2017 – against the highest global value of 8.98 for Iceland, and between the highest African value of 5.88 for Mauritius and the lowest 0.96 for Eritrea. Cameroon thus ranked at 149 out of the 176 countries assessed, with more than twenty African countries ranked above it. On affordability of the internet, Cameroon’s ranking has also slightly improved – currently ranked 50, up from 53 in 2015, out of 60 countries. This still makes internet access in Cameroon among the most expensive of the countries surveyed.

Meanwhile, internet shutdowns, arrests and intimidation of online critics, and censorship of online content raise concerns about the government’s commitment to nurturing a sustainable and inclusive digital society.

ICT Legal and Regulatory Frameworks

The Cameroonian Constitution provides for freedom of expression, freedom of the press and of communication. It states: “the freedom of communication, of expression, of the press, of assembly, of association, and of trade unionism, as well as the right to strike shall be guaranteed under the conditions fixed by law”.

Relevant agencies governing the sector include the Telecommunication Regulatory Agency (ART), and the National Telecommunications Agency (ANTIC) – both under the mandate of the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications (MINPOSTEL). Other entities such as the Ministry of Communication and the National Council of Communication also has regulatory and advisory roles with regards to media.

These agencies are guided by key laws that govern ICT including Law n° 98/014 of July 14, 1998 governing telecommunications and its amendment of December 29, 2005; Law n° 2010/013 of December 21, 2010 on e-Communications, and its amendment of April 2015; Law n° 2010/012 of December 21, 2010 on Cyber Security and Cybercrime; and Law n° 2010/021 of December 21 2010 governing e-Commerce. Other legalisation related to ICT are the Framework Law n° 2011/012 of May 6, 2011 on Consumer Protection, Law n° 2001 / 0130 of July 23, 2001 establishing the minimum service in telecommunications, and Law n° 98/013 of July 14, 1998 on competition which governs all sectors of the national economy.

The 2014 Law on the Suppression of Terrorist Acts, which was enacted to support the fight against terrorism and growing threats from the jihadist group Boko Haram, has been used as a tool to suppress journalism and opinion critical of the government under the guise of preventing the spread of fake news and threatening national security. In January 2018, the Minister of Justice issued a directive to magistrates to “commit, after clear identification by the security services, to legally prosecute any person residing in Cameroon who uses social media to spread fake news”.

A new law is the 2019 Finance Act, which under Section 8, introduces taxation on software and application downloads produced outside of Cameroon, at a flat rate of 200 Central African Francs (CFA), equivalent to USD 0.34, per download. Whereas the government is yet to issue implementation guidelines for the taxes, once in effect, they will result in additional costs for digital platform users.

Access and Affordability

Article 4 of the 2010 eCommunications law states that every citizen “has the right to benefit from electronic communications services”. The same law establishes a Universal Service Access Fund, aimed at ensuring equal, quality and affordable access to services (Articles 27-29). Whereas internet and mobile telephony have registered growth, access and affordability remain a challenge, especially among rural and poor communities. Currently, the average cost of 1GB of data is 2,000 CFA (USD 3.4) per month, and with the proposed levy of 200 CFAs (USD 0.34) on software and application downloads, costs are expected to further increase. With an estimated per capita income of USD 1,500 in 2018, the prevailing rates are over and above the Alliance for Affordable Internet’s recommendation of 1GB of data costing 2% or less of average monthly income.

Gender Digital Divide

A 2015 report by the Web Foundation found that in Cameroon only 36% of women compared to 45% of men were internet users. The key factors inhibiting women’s access to the internet and digital devices in Cameroon included literacy levels, cost relative to income, access to devices, perceived relevance and usefulness, lack of time and poor infrastructure. Towards addressing the digital gender divide, the National ICT Strategic Plan 2020 states among its objectives the need to “support the development of female skills in the field of digital engineering“, and to “support technological and scientific vocations for women“. However, these objectives are not linked to any specific projects within the plan’s priority action areas.

Meanwhile, without much in the way of provisions for gender, cultural and linguistic diversity, the country’s ICT laws remain largely silent on diversity and inclusion within the ICT sector. Further, seven years since its passing, the Framework Law on Consumer Protection, which includes provisions on consumer rights and quality of services within the technology sector, remains largely unenforced due to the absence of implementation guidelines.

Privacy and Data Protection

Cameroon has no data protection or privacy law. However, the national Constitution amended by the Law N°. 96-06 of 18 January 1996, guarantees privacy of communications in its preamble, stating that “the privacy of all correspondence is inviolate. No interference may be allowed except by virtue of decisions emanating from the Judicial Power”. The 2010 Cybersecurity and Cybercrime law also provides for the privacy of communications under Article 41 and outlaws the interception of communications under Article 44. The obligation for service providers to guarantee users’ privacy and the confidentiality of information is covered under Articles 42 and 26.

According to Article 26(1); “Information system operators shall take all technical and administrative measures to ensure the security of the services offered. To this end, they should be equipped with standardised systems that enable them to identify, evaluate, process and continuously manage the risks related to the security of information systems in the context of services offered directly or indirectly”. However, the law does not specify the guiding principles for the collection and processing of personal data, nor users’ right to access and update such data.

Network Disruptions

The government of Cameroon has in the past initiated two internet shutdowns in the Anglophone region of the country, which together lasted 240 days and drew international condemnation. The shutdowns were imposed in the wake of ongoing strikes, fatal violence and protest action against the alleged “francophonisation” and marginalisation of English speakers who claim that “the central government privileges the majority French-speaking population and eight other regions.” It is estimated that the regional internet shutdown cost USD 38.8 million in addition to affecting access to public services, education, and daily livelihoods.

Guaranteeing an Inclusive Digital Space in Cameroon

Cameroon’s government has professed its intention to leverage the digital economy for sustainable development and to establish an enabling legal and regulatory framework. However, developments such as taxation of application downloads, internet disruptions, and limited efforts to bridge the digital gender divide, indicate a shrinking digital space and are likely obstacles to the uptake of ICT. Efforts are thus necessary to ensure a digital environment that is both open and accessible to all, upholds users’ safety and security, and guarantees constitutional rights. These efforts should include a strengthened legal framework with implementation guidelines to ensure enforcement, compliance monitoring, and accountability.

Moreover, the adoption of a specific law on privacy and data protection is recommended, so as to guarantee the principles of anonymity and consent, and in line with international best practice. For civil society organisations, it is recommended to intensify advocacy against regressive policy and practice including internet disruptions, and the enforcement of consumer protection and universal services. Crucially, civil society should play an active role in policy consultative processes and citizen sensitisation on digital rights and literacy.

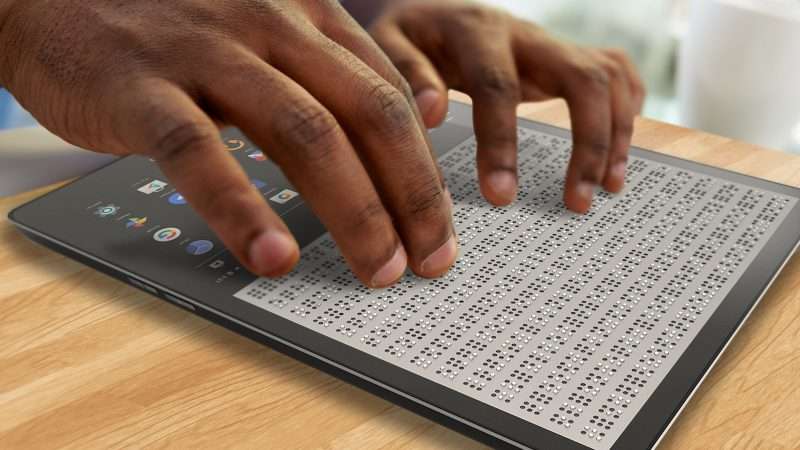

‘People With Disabilities Left Out in ICT Jamboree’

By Marc Nkwame |

As more Tanzanians join the digital world of Information Communication Technology (ICT), the majority of people living with disabilities have been left out, according to stakeholders.

It has been observed that in their quest to optimize profits, equipment suppliers, content producers and mobile communication service providers skip the needs and rights of persons with disabilities wishing to access such services.

Speaking during a special awareness workshop for Information Communication and Technology accessibility among persons with disabilities, the coordinator, Paul Kimumwe from the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for Eastern and Southern Africa (CIPESA) pointed out that it is high time countries formulated special laws to ensure that marginalized groups are also catered for when it comes to such services.

“And if countries have such policies in place, there is the need for legislators to push for their execution, as it seems mobile service providers cater only for a physically able clientele,” he specified.

His observation was also reflected in an assessment tool for measuring mobile communication accessibility for persons with physical disabilities deployed among participants during the just ended workshop on how ICT development side-lined people with special needs.

Dr Eliamani Laltaika, a lecturer from the School of Business Studies and Humanities at the Nelson Mandela African Institute of Science and Technology (NM-AIST), said the society’s mentality and personal stigma contribute in how ICT establishments view the needs of disabled persons.

“Unlike in the past, people should now realize that in the modern era, all is needed for a person to be useful is a healthy brain not peculiar appeal,” he cautioned.

According to the Don, it is usually the persons with physical disabilities that can prove to be extremely good intellectually and especially in Information Communication Technology (ICT), which means once empowered they can perform better than their physically fit counterparts.

Participants realized that mobile handsets are designed for people with hands and those with strong eye sights, while traders and phone service providers are yet to import gadgets that can cater for people without sight or hands.

Ndekirwa Pallangyo, representing the regional chapter for the Federation of Disabled Persons’ Associations in Tanzania (SHIVYAWATA), admitted that people with disabilities have been left out in ICT development.

“And the worst part of it is that even persons with disabilities themselves are unaware that they have been side-lined,” he said, underlining that when it comes to attending to the needs of the physically handicapped, it is important to consider individual requirements.

“There are those who are physically fit except for their sight. Others have impaired hearing, some can’t walk while there are those with no hands, etc. therefore each group need to be handled according to needs,” the activist added.

Originally published on IPP Media

Recherche sur la liberté d’expression sur Internet au Sénégal

Par Diouf Astou, Jonction |

Aujourd’hui, les technologies de l’information et de la communication (TIC) constituent des leviers formidables pour promouvoir et défendre les droits de l’homme. Elles offrent plusieurs espaces d’expression et de ce fait contribuent à l’exercice du droit à la liberté d’expression.

Toutefois, les Etats ne cessent de vouloir réduire ces espaces numériques d’expression « soit en procédant à l’adoption de lois et réglementations répressives, soit en procédant à la violation des droits numériques par des arrestations et intimidations des usagers d’Internet, dans le but de catalyser la libre expression des internautes et la participation citoyenne à l’exercice de la démocratie ».

C’est dans ce contexte que Jonction a procédé à une recherche sur la liberté d’expression sur internet au Sénégal. Cette étude a pour objectif principal de servir comme outil de plaidoyer et de renforcement des capacités à l’intention des parties prenantes (Etat, secteur privé et société civile) sur les questions et enjeux de la liberté d’expression sur Internet et de la confidentialité sur Internet afin de construire une société de l’information respectueuse des droits de l’homme. Elle servira également de référence pour tous ceux qui souhaitent en connaitre un peu plus sur la liberté d’expression sur Internet au Sénégal.

Cette recherche a été possible grâce au soutien du programme Africa Digital Rights Fund (ADRF). Ce projet est initié par Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA).

Le programme Africa Digital Rights Fund (ADRF) a pour objectif « de mettre en œuvre des activités qui font progresser les droits numériques, notamment le plaidoyer, les litiges, la recherche, l’analyse politique, la culture numérique et le renforcement des compétences en sécurité numérique ». L’ADRF a été développé pour renforcer les capacités locales en matière de recherche fondée sur des données probantes, de plaidoyer collaboratif et d’engagements politiques efficaces en réponse aux développements réglementaires et pratiques qui affectent la liberté de l’Internet dans la région.

Recherche sur la liberté d’expression sur Internet au Sénégal

L’auteur de l’étude est une juriste du nom de Astou DIOUF, elle coordonne le département de recherche à Jonction, une organisation de promotion et de défense des droits numériques. C’est une passionnée dans la défense et la promotion des droits numérique, notamment la cybercriminalité, la liberté d’expression, les données à caractère personnel et la cyber sécurité. Elle a soutenu son mémoire sur : l’instruction préparatoire en matière de Cybercriminalité pour l’obtention du diplôme de Master 2 en Droit à l’Université Cheikh Anta DIOP de Dakar.

Elle est également l’auteur d’une Etude Critique de la Stratégie Nationale de Cybersécurité du Sénégal.

Mapping the Impact of Digital Technology from Network Disruptions to Disinformation

By Rocio Campos |

Signed by African journalists during a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) seminar in May 1991, the Declaration of Windhoek is a statement of free press principles that led to the proclamation of World Press Freedom Day (WPFD) on 3 May by the UN General Assembly in 1993. This year, the Global Network Initiative(GNI) is proud to join UNESCO, the African Union, and the Government of Ethiopia for the 26th celebration of WPFD in Addis Ababa under the theme, “Media for Democracy: Journalism and Elections in Times of Disinformation.”

On 3 May, GNI Policy Director Jason Pielemeier and representatives from GNI members the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA), Facebook, and the International Media Support (IMS), together with the Ethiopian journalist Abel Wabella will participate in the session: “Understanding Electoral Information Flows: Mapping the Impact of Digital Technology from Network Disruptions to Disinformation.” This workshop will build on an earlier colloquium organized by GNI and UNESCO titled Improving the Communication and Information Ecosystem to Protect the Integrity of Elections.

In 2019, 62 countries will elect leaders who will govern 3.28 billion people worldwide. Hence, it is paramount to understand the impacts of digital technology on information flows during elections and bring to the table the perspectives of different stakeholders.

Are Transparency and Access to Information Enough to Secure Free Elections?

According to UNESCO “Internet and digital technologies allow candidates a direct means by which to communicate with the voting public. However, some digital technologies used to influence people’s choices escape scrutiny — such as whether, for example, advertising complies with the rules of electoral authorities. Without effective access to information and transparency, the integrity and legitimacy of elections can be compromised. We need technology companies and governments that are more transparent, and that respect the rules and regulations of elections, in order to guarantee free and fair elections.”

GNI information and communications technology (ICT) company members face increasing orders from governments to disrupt networks and restrict access to Internet services. Such orders often take place during protests or elections with significant consequences for users and journalists around the world. GNI members (ICT companies, human rights and press freedom organizations, academics, and investors) work to counteract these trends and protect freedom of expression and privacy rights in a variety of ways. For instance, on the issue of network interference, Netblocks’ Internet observatory has collected evidence of blocking of a political party website in Pakistan in the 2018 election and CIPESA released a report that documents the relation between network disruptions and elections in Africa. Others like the #KeepItOn coalition have developed infographics guiding users on how to install Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) anticipating Internet disruptions, as seen in the Nigerian election last February.

Elections have also become the focus of disinformation campaigns, making online platforms vulnerable targets for the dissemination of divisive and false narratives. Multistakeholder engagement can play a key role to confront this evolving assault on the Internet affecting democratic processes. In July 2017, Google and Jigsaw unveiled Protect Your Election with free tools to help voters get accurate information in the Kenyan election.[1] In the U.S., Pen America recently released a report, which analyzes efforts to counter fraudulent news in the 2018 midterm election, stressing the importance of social media platforms, candidates and political parties stepping up efforts to keep fraudulent news from polluting the 2020 election cycle. Research centers like the Center for Data Innovation are discussing the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) to fight disinformation in European elections, while organizations like Freedom House have developed tools that estimate Internet censorship, i.e., Internet Freedom Election Monitor.

GNI‘s session will take advantage of the expertise of panelists and participants to map the different ways in which digital technology impacts election-relevant information flows, as well as the inter-relationships between these impacts. The goal is to help policymakers, companies, elections administrators, elections observers, media, and other stakeholders identify and mitigate risks, improve planning and coordination, and enhance transparency around their efforts to support elections. Active multistakeholder engagement can play a key role to strengthen transparency and access to information and prevent them from being compromised during elections.

Don’t miss GNI’s panel on 3 May at 14:00–15:30 EAT and follow IMS’ @andreasr | Addis Zeybe’s @Abelpoly | CIPESA’s @ChewingStones | CPJ’s @muthokimumo | Facebook’s @emigandhi | GNI’s @pielemeier #WorldPressFreedomDay

Relevant resources:

- 2019 WPFD’s provisional agenda

- UNESCO on freedom of expression

- GNI’s one-page guide: Weighing the Impact of Network Shutdowns and Service Restrictions

- GNI’s Principles on Freedom of Expression and Privacy

- Improving the Communication and Information Ecosystem to Protect the Integrity of Elections (Conclusions of GNI/UNESCO Colloquium, February 2017)

[1] See: Freeman, Bennett, Shared Space Under Pressure Business Support for Civil Freedoms and Human Rights Defenders, p.74

This article was originally posted here