By CIPESA Writer |

Sudan descended into a brutal armed conflict on April 15, 2023. The conflict pits the transitional government under the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) against a paramilitary group, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). At least 600 people have been killed, 5,000 injured, 700,000 internally displaced, and 100,000 have fled the country. Also, various essential services, including telecommunications, print and broadcast media, have been disrupted.

The current power struggle between the SAF and RSF is a major setback to the fragile country’s attempt to transition to democratic and civilian rule after the 2019 ouster of former dictator Omar al Bashir. Ideological differences over the future direction of the country, and factors such as religion, ethnicity, political and economic interests, are key drivers of the conflict. At the centre is the internet, which has been used to spread information and propaganda, recruit and mobilise fighters, and coordinate attacks. The internet has also allowed disparate actors to document the conflict, provide humanitarian assistance, and coordinate protests.

Internet disruptions

On April 16, the second day of the conflict, telecom operator MTN Sudan received an order from the telecommunications regulator to shut down the internet. Within hours, the operator reportedly received another order to restore access to the internet. The Telecommunication and Postal Regulation Authority (TPRA) regulates the telecommunications sector in Sudan. It remains unclear whether the TPRA issued shutdown orders to other Internet Service Providers such as Zain Sudan and Sudatel, as only MTN Sudan admitted to receiving the order. Most internet measurement tools did not indicate a disruption, but Cloudflare confirmed a drop in internet traffic in Sudan on April 15.

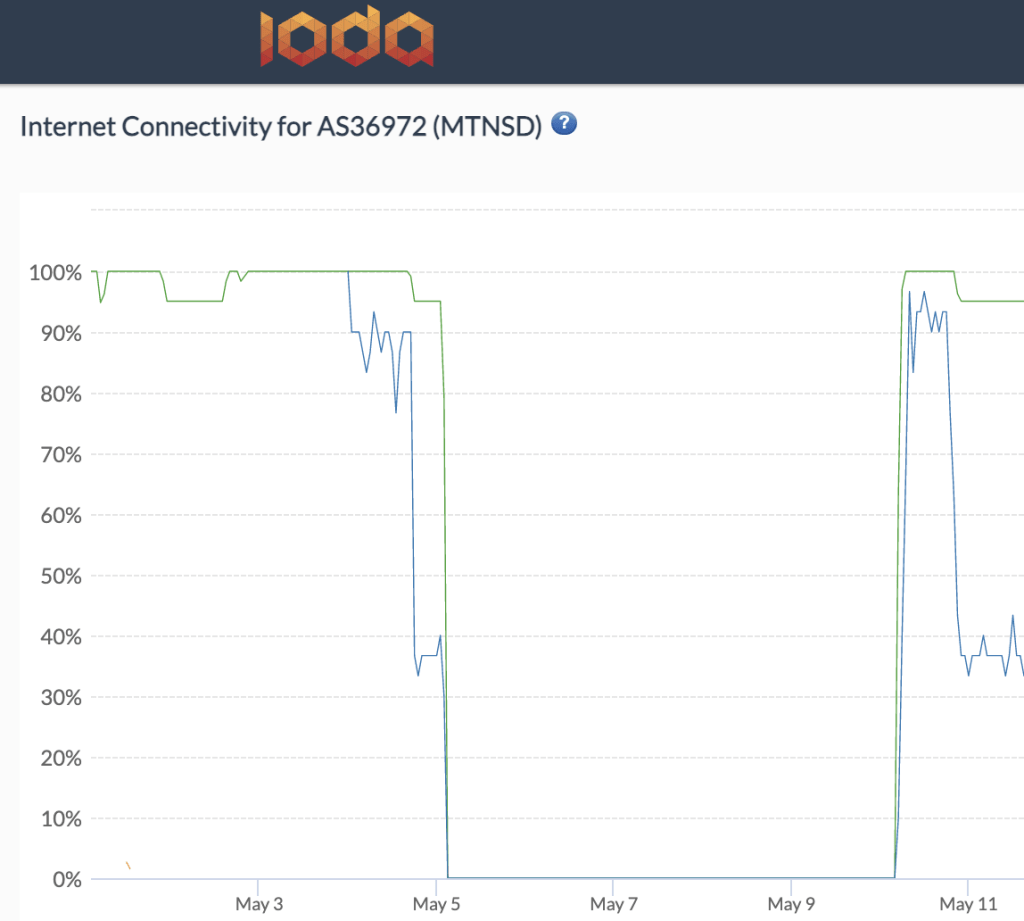

The order to restore MTN Sudan services did little to enable access as disruptions to the national grid left the country without electricity supply. Indeed, on May 5, MTN Sudan announced that its network had been disrupted by power outages. The operator also said its teams were unable to deliver fuel to generators as a result of the ongoing fighting in the city.

Measurements from Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA) confirmed MTN’s outage.

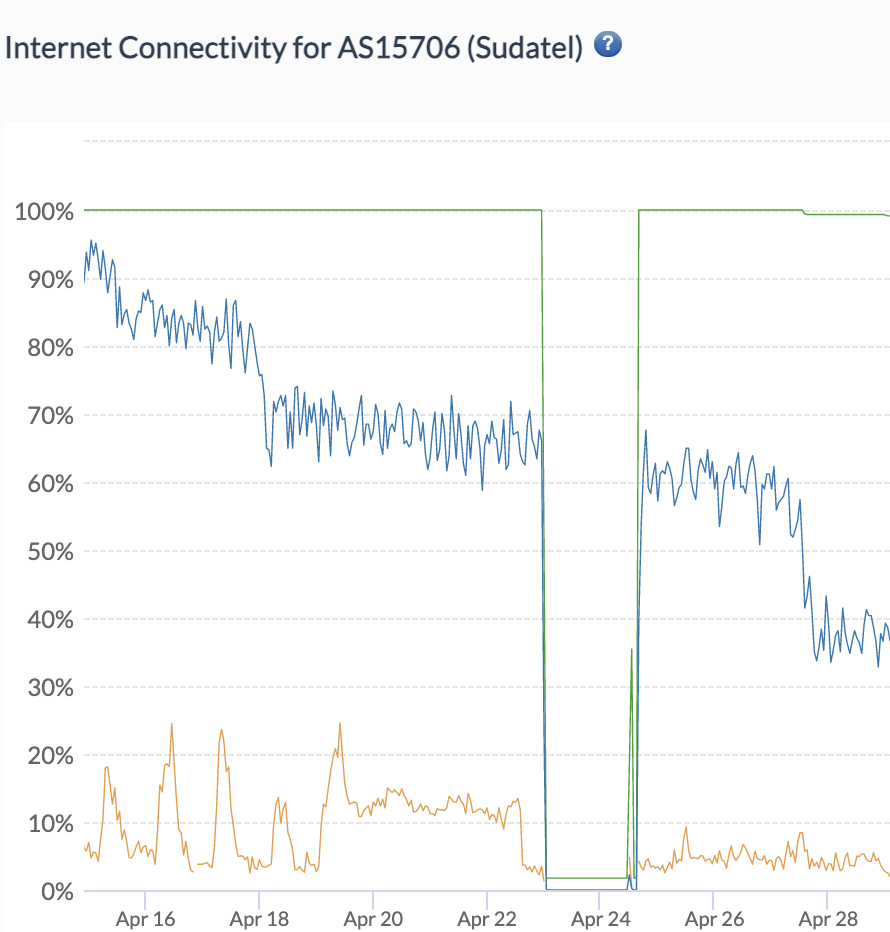

Similarly, state-owned Sudatel Mobile, commonly known as Sudani, on May 5, 2023 announced network disruptions due to unreliable power supply and the inability to fuel generators. Earlier on April 23, the Sudani network, which is the main government service provider, was disrupted after fighters of the RSF seized one of its two data centres in Khartoum.

Meanwhile, Netblocks, another internet measurement organisation, reported that the services of privately owned Canar Telecommunications Company had collapsed amidst the conflict.

Disruptions to internet access in Sudan are commonplace, with authorities justifying them as necessary to ensure “national security and emergency state”. The longest shut down was reported in December 2018 lasting up to 68 days, followed by another in June 2019, lasting 37 days and in October 2021, lasting 25 days. The country was ranked as Not Free in the 2022 Freedom on the Net report, given its record of imposing obstacles to internet access, limitations on accessing online content, and violating rights of internet users.

The June 2019 shutdown was initiated amidst protests that saw more than 100 protestors killed while the October 2021 shutdown was initiated during a SAF coup. In the aftermath of the coup, there were four incidents of internet disruptions including to control protests, avoid cheating in exams and curb tribal conflict.

Enabling Legislation

Sudan has a history of using the 2018 Telecommunications and Postal Regulation Act (TPRA), the 1997 law of Emergency and Public Safety, and the 2007 Armed Forces Act (amended in 2019) to block digital communications. The authorities depend on these using vague terms such as “national security” and “public safety” as a justification for the orders.

Previously, the TPRA has relied on articles 6(J), 7.1, and 7.2(A) of the TPRA law of 2018, to justify the shutdown, such as the one of October 2021. These articles assign the TPRA the responsibility of “defending the national security and the higher interests of Sudan,” and “the state’s obligations and requirements in the field of national security and defence, and national, regional and international policies.” The term “national security” is vague, which enables the authorities to misuse it in their interests.

Sudan has ratified key international human rights instruments including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR), which guarantee the right to freedom of assembly, freedom of expression, and the right to receive, impart and disseminate information. The various disruptions to communications which the country has instituted appear to violate the provisions of these international instruments.

Meanwhile, the National Security Law 2020 gives state authorities sweeping powers to intercept, search and seize communications for purposes of national security. Military forces that staged the October 2021 coup appeared to use the 2020 law to search individuals’ phones to delete documentation of human rights violations that were perpetuated.

In the current crisis, some citizens have reported that RSF forces are inspecting the content of citizens’ devices to verify if they are supporters of the SAF or they provide information to the group. The Emergency Lawyers Committee has previously revealed that there was widespread surveillance by authorities. Recent reports also point to acquisition of spyware technology by the RSF. In 2012, the Sudanese Intelligence reportedly purchased spyware from the Hacking Team – apparatus that is likely still in use in the country.

Propaganda war

Whereas internet penetration in Sudan stands at only 28.4 percent, the network disruptions create an information vacuum. When fighting broke out, the RSF seized control of state broadcasters and ceased transmission. Hours later, Sudan TV restored broadcasting via satellite, while Omdurman FM – the national radio – started broadcasting again but through AM transmissions. Both radio and television stations are primarily broadcasting SAF news and propaganda that has translated into risks of real life harm. For instance, false news of territories under SAF control has led citizens to flee to those territories, only to find them under the control of RSF, which, according to Human Rights Watch, has a history of committing war crimes.

As the conflict continues it is crucial that the warring factions and telecommunications actors keep communication networks on as disruptions limit citizens’ access to information and undermine media freedom and freedom of expression. Furthermore, the disruptions limit the effectiveness of humanitarian efforts and hamper citizens’ access to essential services and safe havens.