By Juliet Nanfuka |

In 2016, activism in Zimbabwe took on a new persona through various social media campaigns that also transformed into offline activity. In a move which critics believe is intended to suppress activism on social media, the national telecoms regulator known as the Postal and Telecommunications Regulatory Authority of Zimbabwe (Potraz) recently drove up internet access prices by up to 500% but following online uproar, the information ministry moved to reverse the decision.

As at the third quarter of 2016, Internet penetration in Zimbabwe stood at 50%. However, increased online use is threatened by a state keen to control online narrative similar to how it has controlled traditional media. Intimidation and arrests are likely to hurt internet freedom in a country where citizens are increasingly using online platforms to criticise the political and economic malaise in the southern African state.

Like many other African countries, internet access remains costly in Zimbabwe. The presence of a Universal Access Fund (USF) meant to reduce internet access costs and fund infrastructure across the county has not helped matters. POTRAZ manages the USF and has been criticised for under-utilising the fund and lacking transparency about its expenditures.

Increased access at lower cost has partly been enabled by service providers offering mobile internet data bundles accompanied with subsidised or “zero rated” access to social media applications such as Whatsapp and Facebook. However, in August 2016, at least three service providers discontinued various promotions following a directive from POTRAZ . The directive was issued shortly after the regulator warned against increasing “abuse” of social media.

“Government is literally, deliberately or accidentally, suffocating the digital revolution by cutting off the lifeblood of the revolution, which is affordable digital and social media access to give citizens an alternative voice.”

TechZim News Blog

According to the 2016 State of Internet Freedom in Zimbabwe report, recent activities by state agencies have breached citizens’ rights guaranteed by the constitution. Proposed laws such as the Data Protection Bill and the Electronic Transaction and Electronic Commerce Bill could further undermine citizens’ rights to free expression and privacy. In addition, the draft Computer Crime and Cybercrime Bill provides for mass surveillance of citizen communications.

In the absence of a cyber law, the Criminal Law and Codification Act (CODE), popularly known as the “insult law”, has been the government’s weapon of choice against critics both online and offline. The law was widely used during the protests in 2016 to invoke harassment and arrest of “trouble-makers”, namely those who oppose or criticise President Mugabe.

Extracted from State of Internet Freedom in Zimbabwe | 2016 report

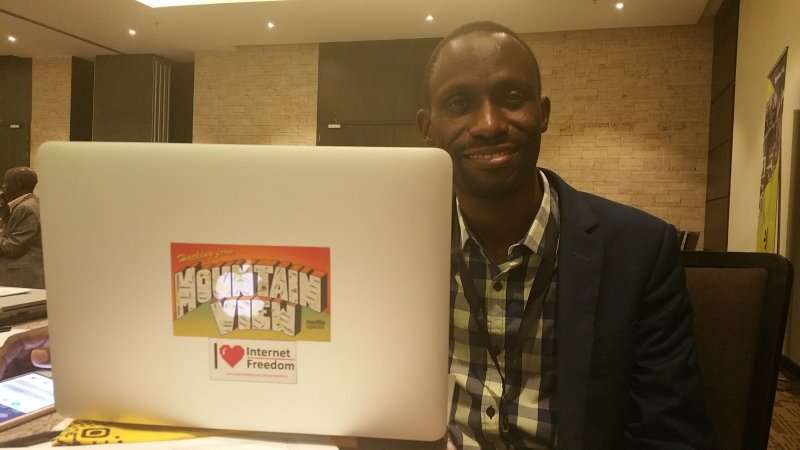

The report by the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) narrates cases of Zimbabweans arraigned before the courts over their online activities. Among the stated trumped-up charges are “criminal nuisance“, “insulting and undermining the president’s authority” and issuance of “treasonous” communiqué criticising Mugabe’s leadership.

Section 61 of the Zimbabwe Constitution guarantees the right to freedom of expression: “Every person has the right to freedom of expression, which includes … freedom to seek, receive and communicate ideas and other information.” While Zimbabwe has no specific law related to internet rights, the constitution also provides for access to information and privacy without explicitly mentioning the online domain.