By CIPESA Writer |

The World Health Organization (WHO) has recognised the potential of technology to enhance health outcomes. The WHO’s Global strategy on digital health 2020-2025 aims to promote the appropriate use of digital technologies for health, taking into consideration health promotion and disease prevention, patient safety, ethics, interoperability, intellectual property, data security (confidentiality, integrity, and availability), privacy, cost-effectiveness, patient engagement, and affordability.

In the wake of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Covid-19), countries in Africa, like their counterparts across the world, have dramatically increased the use of digital technologies in the health sector, including in diagnosis, disease surveillance, education, research, data management, and care delivery. At regional level, the African Union (AU) and the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are setting up digitalisation policy frameworks for social-economic transformation including in the health sector.

For instance, the AU’s Digital Transformation Strategy 2020-2030 cites the health sector (among others) as critical to driving digital transformation for prosperity and inclusivity. The Africa Union Data Policy Framework also emphasises that improved, integrated data systems directly contribute to improved health.

In May 2023, the Africa CDC launched its Digital Transformation Strategy 2023-2030 to harness digital health to leapfrog some of the barriers affecting healthcare and public health. The strategy alludes to the challenge of poor quality of health data and poor governance and management practices of data ecosystems – such as poor coordination between governments and partners that fund these data infrastructure.

The AU and WHO assert that digital health solutions should benefit people in a way that is “ethical, safe, secure, reliable, equitable and sustainable”; and that they should be developed with principles of “transparency, accessibility, scalability, replicability, interoperability, privacy, security and confidentiality”. However, evidence from some African countries shows a complicated picture.

Research has found that in responding to the Covid-19 pandemic, many countries adopted regulations and practices, including deploying disease surveillance technologies and untested applications, to enable them collect and process personal data for purposes of tracing, contacting, and isolating those suspected to be carrying the virus and those confirmed to carry it. These measures were quickly adopted, often without adequate regulation or oversight.

The reality of the explosion in use of digital tools in the health sector has not been adequately studied. Risks posed by these technologies to patient privacy and data protection, creation of data silos and duplication, and real world harm to patients are issues that should be investigated to inform efforts to institute relevant and effective safeguards.

Take an example of Uganda:

Uganda has a fairly robust national data ecosystem. The Uganda Bureau of Statistics is among the most efficient statistics agencies in Africa and it conducts major surveys on schedule. Various private entities, Non-Government Organisations (NGOs) and development partners have also introduced new tech-based data collection instruments often presented as plugging gaps and aiming to strengthen the data ecosystem. This progressive data collection culture has, however, inadvertently created a problem: multiple siloed data and information systems, many of them not speaking to each other.

The country’s health sector is among the top funded – both by government and development partners – and has one of the strongest data and information systems.

Since 1985 Uganda’s health ministry has used the Health Management Information System (HMIS) to collect health-related data so as to improve health care management decisions at all levels of the health system. The HMIS and its associated District Health Information System (DHIS2) are used to collect routine health data from the lowest health unit to the national referral hospital. The DHIS2 is an open source, web-based platform used in many countries to collect health data in clinics and hospitals.

All state health facilities and privately-owned ones that are supported by the government, are expected to use the HMIS/DHIS2 systems and to submit routine patient data, according to the ministry’s HMIS procedure manual.

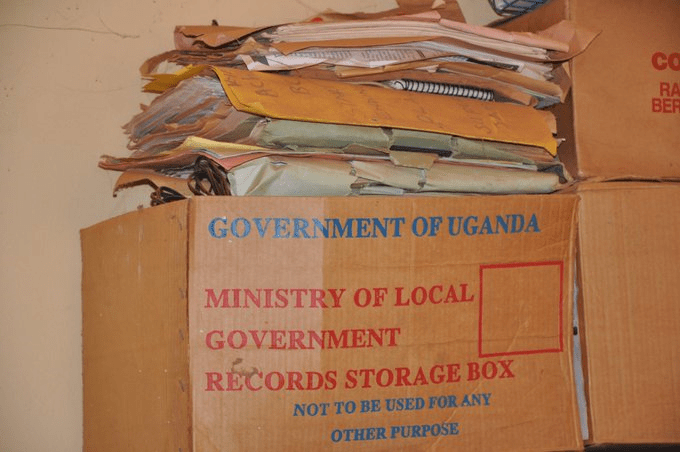

While the HMIS is meant to provide data for monitoring and evaluating the progress of the health sector, over the years, the system has faced multiple challenges. It is largely paper-based, leading to poor quality of the data collected. Limited understanding and skills amongst health workers on HMIS tools and inadequate human resource capacity to analyse and curate the data add to the problem. Low involvement of private health providers in contributing data to the system is yet another challenge.

Uganda Embraces Technology for Health

In 2016, Uganda developed an eHealth Policy followed in 2017 by an eHealth Strategy, in whose preamble the ministry states that it recognises the potential of technology “in transforming healthcare delivery by enabling information access and supporting healthcare operations, management, and decision making”. The strategy stated that Uganda’s health sector was characterised by fragmented and siloed pilot projects and information systems with significant barriers to effective sharing of information. The policy aimed to ensure better coordination in the innovation space where multiple players aspire to improve health data management and service delivery using digital technologies.

In May 2023, the health ministry launched the new Uganda Health Information and Digital Health Strategic Plan 2020-2025 aimed at further strengthening the health information ecosystem in the country by promoting responsible use of digital tools to document and share patient data while maintaining coordination among all players.

These efforts by the health ministry align with Uganda’s digitalisation agenda as part of its National Development Plan (NDP) III, the country’s blueprint to becoming a middle income country.

The health ministry’s 2020-2025 Strategic Plan acknowledges challenges the government faces in digitising and transforming the health data ecosystem:

- Limited qualified cadres in health information systems (HIS) at all levels, especially at lower levels of the health system.

- Inadequate Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) and capacity for HIS management including data security, data sharing, reporting and implementation at health facility and community levels.

- A multiplicity of duplicate and uncoordinated health information platforms with limited integration into the national HIS.

- Limited individual skills, system capabilities, financial resources and a lack of SOPs for supporting, using and maintaining digital health resources, equipment and infrastructure.

- Limited use of electronic health and medical records for clinical care, research and routine data analytics that would aid policy and pragmatic decision-making.

The above challenges are exacerbated by a shortage of supporting infrastructure. The country’s internet penetration rate stands at 60%, but internet costs are prohibitively high, and many health facilities lack connectivity. Furthermore, the electricity access rate stands at just 57%.

Digital Health Applications and Data Governance

The Covid-19 pandemic saw a proliferation of pandemic-related innovations in Uganda, including for contact tracing, and digitisation of vaccination data. Yet not many of the innovations did not adhere to established data protection regulations. Similarly, the Public Health (Control of COVID-19) Rules, 2020 and the Public Health (Prevention of COVID-19) (Requirements and Conditions of Entry into Uganda) Order, 2020 did not specify measures to guarantee data protection.

The Personal Data Protection Office (PDPO) was not operationalised until August 2021 – deep into the enforcement of the country’s disease surveillance measures. To-date, there is no indication that the Office had any oversight over the enforcement of COVID-19 Rules and the Order of 2020 in accordance with the data protection law.

Health Data Regulation: Lessons from COVID-19 Surveillance in Kenya and Uganda, June 2023.

More recently, a coordinated response to the Ebola virus outbreak in Uganda enabled its swift end partly due to a centralised repository of data on Ebola cases from verified sources, which provided vital information to various stakeholders. Another data tool by WHO called Go.Data improved Ebola surveillance, contact tracing and decision making, rendering the epidemic easier to manage. The tool revolutionised data collection, collation and analysis, which are critical in disease outbreaks situations by enabling frontline health workers and District Health Teams (DHTs) to handle information management for contact follow-up and reporting in real-time. And yet, just like with the Covid-19 pandemic, there has been no transparency or audits on these tools’ data protection practices.

Accordingly, it is imperative that Uganda puts in place regulatory standards and guidance to effectively reap the benefits of innovation in the health sector. The health ministry and Makerere University have developed a handbook that provides a set of requirements to guide the development of digital health standards and adoption of digital health data standards to enhance health information management and decision-making processes across the health sector.

As part of rolling out those standards, it will be crucial for the ministry to establish Working Groups made up of a multi stakeholder group of experts that can review innovations in the health data management sector, including their privacy credentials and general added value. Furthermore, they would establish benchmarks and best practices in the health data innovation space, such as on collaboration, to avoid duplication of efforts and promote interoperability. Meanwhile, other existing frameworks such as the Uganda Bureau of Statistics 2018 rules for conducting surveys and censuses should be strictly enforced for both state and non-state actors.For its part, the Office of Personal Data Protection (PDPO) is now fully operational and provides benchmarks on how to handle personal data. The PDPO has enforced registration of data collectors, controllers and processors and rolled out capacity building as well as awareness raising programmes. Dedicated interventions by the PDPO targeting the health sector will ensure that actors and entities are compliant with regulations, thereby ensuring patient data confidentiality and integrity.