The Collaboration on International ICT Policy in East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) and Paradigm Initiative Nigeria (PIN) to co-host discussion on online safety matters in Africa, during November and December 2013.

Background

Africa’s internet usage continues to grow steadily, with an estimated 16% of the population on the continent using the internet. The increased availability of affordable marine fiber optic bandwidth, a rise in private sector investments, the popularity of social media and innovative applications, and increased use of the mobile phone to access the internet, are all enabling more people in Africa to get online. In turn, there are numerous purposes to which users in Africa are putting the internet‐from mobile banking, to connecting with fellow citizens and with leaders, tracking corruption and poor service delivery, innovating for social good, and just about everything else.

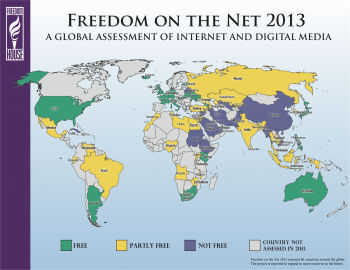

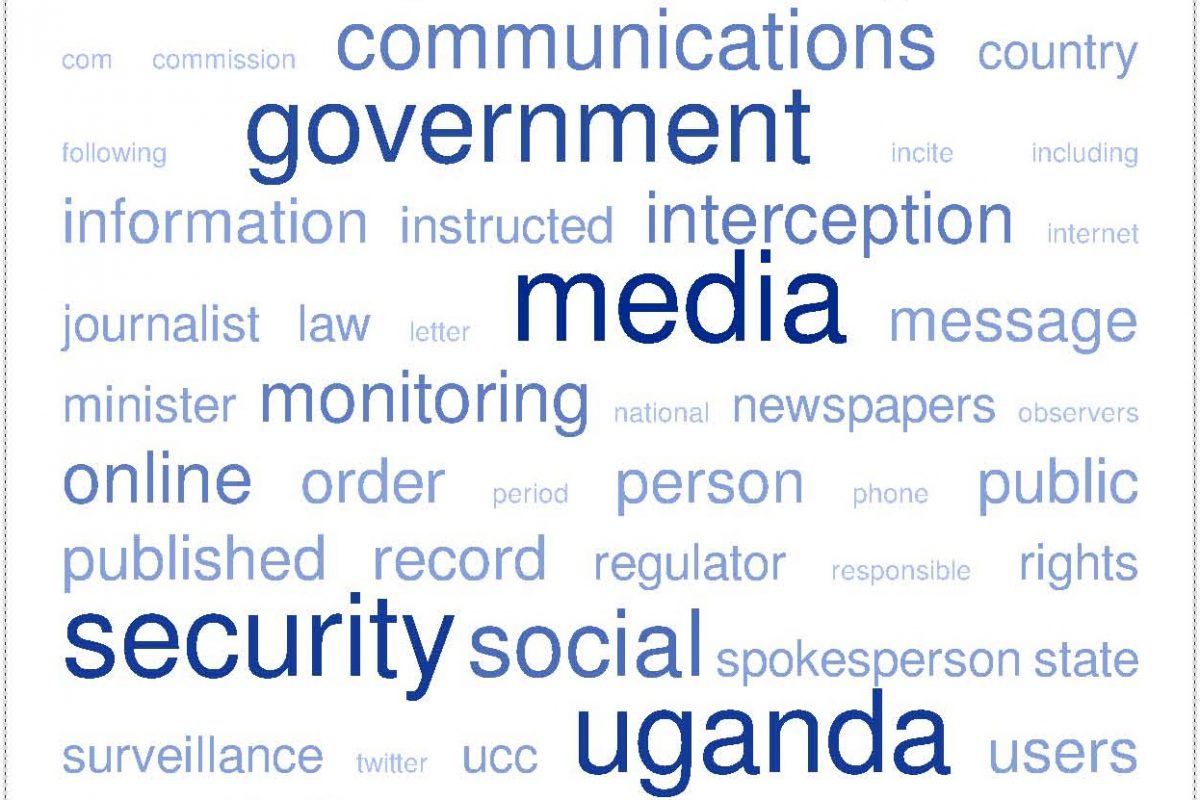

The increasing usage of the internet, however, has in some countries attracted the attention of authorities, who are eager to provide caveats on the openness of the internet and the range of freedoms which citizens and citizens’ organisations enjoy online. The popularity of social media, the Wikileaks diplomatic cables saga and the Arab Spring uprisings have led many governments including those in Africa to recognise the power of online media. In a number of African countries, there are increasing legal and extra-legal curbs on internet rights, in what portends tougher times ahead for cyber security.

PIN and CIPESA to Lead on Internet Freedom Discussions

The Collaboration on International ICT Policy in East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) and the Paradigm Initiative Nigeria (PIN) will co-host an online internet freedom forum during November and December 2013. The purpose of this forum will be to discuss key online safety matters in Africa. The forum aims to attract discussions from key ICT experts both within Africa and outside Africa.

The outcomes of the discussions will feed into a report that will be presented at the first African Internet Freedom Forum to be held in 2014. Furthermore, it will inform the work of CIPESA, PIN and their partners that are working in the area of online freedoms.[1]

Format of the discussions

Discussions will be hosted on selected online platforms in Uganda, Kenya, Nigeria and a mailing list comprising Africa Internet Governance experts. Identified platforms are:APC Africa IG Mailing List; KICTANet (Kenya) mailing list; Information Network (Uganda) mailing list; Naija IT Professionals mailing list; West African IGF mailing list; and FOI Coalition (Nigeria) mailing list.

The lists will be moderated by a representative from both CIPESA and PIN. Each week, a new topic with guiding questions will be introduced on the listserves and a summary provided at the end of each week. A draft report will be made available at the end of the fourth week. This too shall be posted back on the mailing lists to capture feedback from participants as well as seek clarification on any issues that might not have been captured well. A final report shall then be made that will feed into the face to face meeting as well as be shared on the targeted platforms and onpartners’ websites.

Discussion Outline

Week 1: November 11-15 Status of Internet Freedom in African Countries: Focus shall be on seeking participants’ views on issues of Freedom of Expression both online and offline; Internet Intermediary Liability; censorship and surveillance incidents; regulations, laws and policies governing freedom of expression online and perspectives on the African Convention on CyberSecurity.

Questions to explore:

- What are the major issues surrounding online freedom of expression in Africa?

- What convergences and tensions exist between freedom of expression and privacy?

- What are the implications of approaching the balance between freedom of expression and privacy from a freedom of expression–centric point of view?

- What actions can governments, civil society, media and the private sector take to balance privacy with freedom of expression online?

- What is the best way to empower users to stay safe online while protecting their freedom of expression?

Week 2: November 18-22 Global Surveillance Revelations and Impact on Africa: Focus will be given to global surveillance incidents like the NSA/Edward Snowden drawing lessons for Africa stakeholders i.e. governments, activists, CSOs and private sector; how to balance privacy while maintainingsecurity for citizens.

Questions to explore

- What can African governments learn from the NSA surveillance and Snowden revelations?

- What are the current technology trends and which cybersecuritythreats raise the greatest concern?

- How are evolving Internet services and technologies, such as mobile and cloud computing services, affecting these security threats?

- Is there any country data, across the continent, on how surveillance has really helped to curb – or prevent – acts of terrorism?

- Are African countries spying on each other? Are there countries that have shown a tendency to breach the rights of other sovereign nations on the continent?

Week 3: November 25-29 Best Practices on Internet Policy in Africa: Discussants will be called to share best practices on internet policies in Africa.

Questions to explore:

- What policies are working in your country and what needs to be streamlined or strengthened?

- Are there African countries that offer a model, or close enough to Best Practice scenarios that can be highlighted for other countries to learn from, or emulate

- What are the signs to look out for in our various countries’ ICT policies, to be sure that the country plans to improve Internet Freedom?

- What worked well for countries that have shown steady progress in the annual Freedom House ratings?

- What can other countries learn from those that have, or are developing, crowdsourced (and citizen-led) Internet Freedom Charters?

Week 4: December 2-6 Recommendations for Africa:Participants shall be called upon to suggest ways to improve internet security, data and privacy protection in Africa.

Questions to explore

- What elements need to be put in place to ensure all Internet users (including citizens, companies, government, etc) continue to have confidence in the Internet?

- How can African civil society organisations engage ICT policy processes to ensure that rights are not traded for security?

- Considering the ongoing discussions around the African Convention on Cybersecurity, what recommendations should be made to improve the text?

- How do activists and rights’ advocates protect themselves in scenarios where government clampdown could affect their work?

- Should African academia incorporate this new reality into classroom discussions? If they should, is there a model to learn from?

Join the conversation

For more information about the online discussions forum, please write to CIPESA via [email protected] or Paradigm Initiative for Nigeria via [email protected]