By CIPESA Writer |

In an era where digital technologies are reshaping every sector including health, agriculture, finance, education and the labour market, Uganda is fast-tracking its ambition to become a fully connected, inclusive digital society. Yet, as the country rolls out its Digital Transformation Roadmap, critical questions remain: Who is being left behind? Who bears the cost of connecting the unconnected? How do we ensure that technological innovation does not come at the expense of human rights protection?

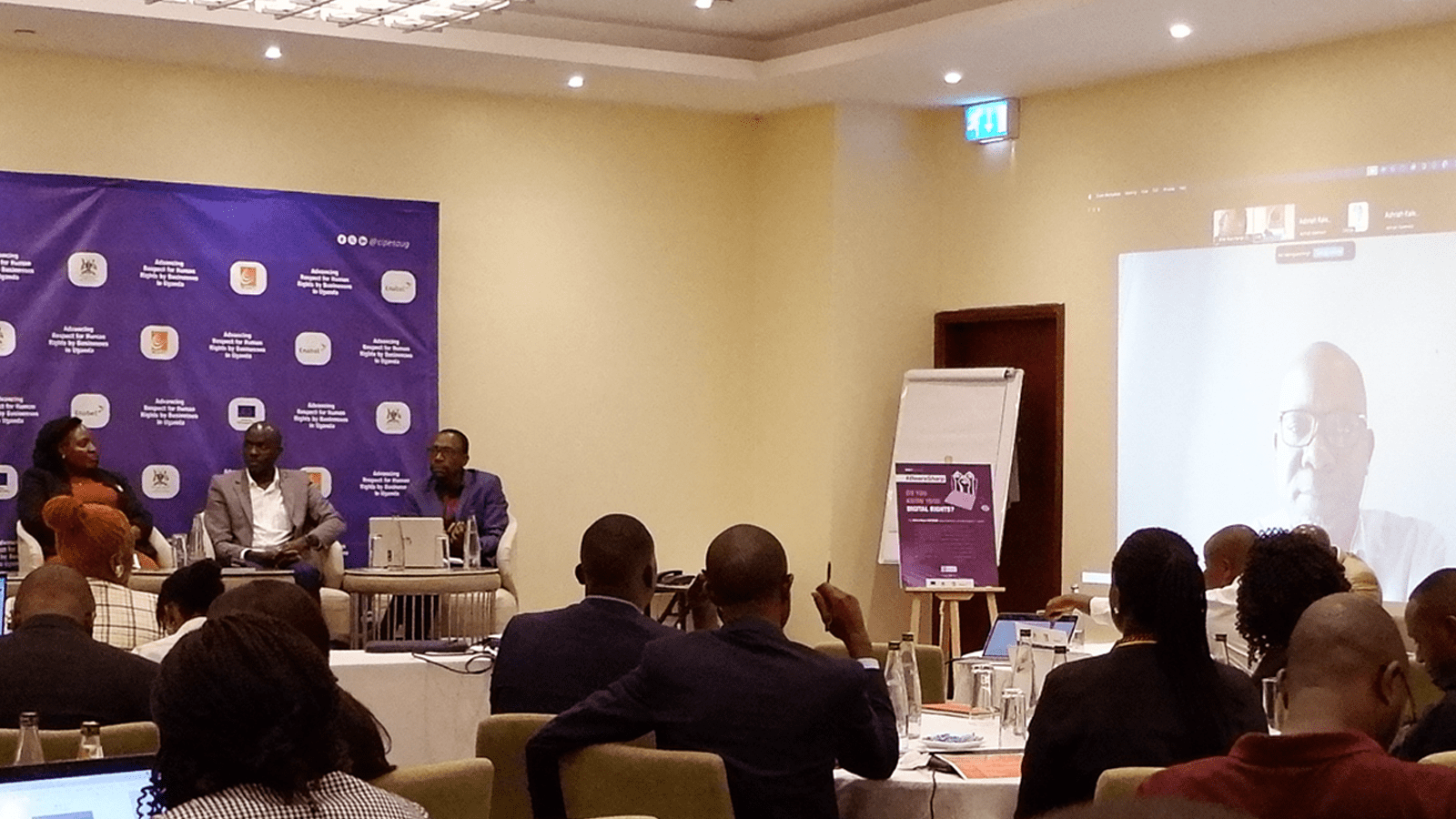

These were the central concerns at the inaugural National Business and Digital Rights Policy Dialogue hosted by the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) on July 23, 2025. The event brought together 55 participants comprising policymakers, innovators, civil society, the private sector, and development partners to explore how Uganda’s digital transformation is affecting human rights, especially data protection, privacy, access, and equity. The dialogue reviewed not just Uganda’s progress, but the power dynamics, policy gaps, and human rights risks shaping digitalisation in business.

The Digital Vision vs. The Digital Reality

Uganda’s Digital Transformation Roadmap sets bold targets: 90% household connectivity, nationwide broadband coverage, and widespread e-service access by 2040. Progress is visible, with over 4,000km of national optical fibre infrastructure laid, and more than 100 digital public services rolled out. Yet, beneath these achievements, gaps in digital literacy, access and utility, as well as funding constraints, persist.

According to the 2024 National Population and Housing Census, Uganda’s population stands at 45.9 million, of whom 50.5% are under the age of 18, representing a massive youth cohort born into a digital world yet often lacking affordable internet access and digital tools. Connectivity gaps are further shaped by geography, with over 75% of the population living in rural areas where infrastructure is limited.

On the gender lens, women who comprise 23.4 million of the population, slightly outnumbering men at 22.5 million, continue to disproportionately face digital access barriers. These range from high data costs, low digital literacy, and limited access to devices and digital infrastructure, especially in rural and remote districts. As one of the panelists during the policy dialogue noted, “Digital transformation is moving fast, but our institutions and communities are not always keeping pace.”

Meanwhile, the informal sector, which employs approximately 80-92% of the country’s workforce, remains largely invisible in national digital strategies and compliance frameworks. This informal sector significantly overlaps with Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs), which are central to Uganda’s economic growth, yet they often operate without proper tools to secure user data or navigate the evolving digital compliance landscape due to limited awareness, resources, and technical capacity.

As businesses digitise, their responsibility to protect users’ rights increases. However, many of them lack the knowledge to protect these rights. Uganda’s laws and enforcement mechanisms also have gaps. As a result, there is weak oversight over fintech platforms and digital lenders, low awareness and implementation of the Data Protection and Privacy Act, rampant digital surveillance, and gendered digital harms, including online harassment.

Data Is Power but Who Holds It?

Uganda’s fast-growing population is generating an unprecedented amount of personal data. The 2024 population census itself relied on tablet-based digital enumeration for the first time. However, while digital data collection is expanding, data governance is not keeping pace. The Personal Data Protection Office (PDPO) and National Information Technology Authority Uganda (NITA-U) are key players, but capacity and resourcing gaps persist. If left unaddressed, digital innovation risks entrenching inequality, with vulnerable populations, especially refugees, informal workers, and low-income women, paying the price for systems that were not designed with their rights in mind.

Digital Rights are Human Rights

The future of work in the advent of technology emerged as a key aspect of digital rights, with Moses Okello of the National Organisation of Trade Unions (NOTU) warning that Uganda’s labour laws have not kept pace with the rise of gig work and digital employment. Millions of informal workers remain unprotected and unaware of their rights in the digital economy. He called for urgent legal reforms and a national strategy that integrates labour protections into digital policy, while urging stronger collaboration with civil society to build grassroots awareness and empower workers to navigate digital transitions.

Ruth Ssekindi, Director at the Uganda Human Rights Commission (UHRC), underscored the commission’s constitutional duty to uphold human rights across both state and private sectors, particularly in Uganda’s fast-evolving digital landscape. She highlighted growing concerns over digital rights violations including uninformed data consent, artificial intelligence (AI) manipulation, child exploitation, and poor data security, noting that these challenges disproportionately affect vulnerable populations amid low digital literacy and weak enforcement.

Ssekindi called on businesses to embrace a broader duty of care that goes beyond tax compliance and profit, stressing the need to respect, protect, and remedy digital rights violations. She also pointed to the persistent gender gap in digital access and urged greater inclusion of women and marginalised communities in digital development. While the UHRC plays a key role in shaping digital governance through legal review, education, and policy oversight, she noted that the commission must be adequately resourced, empowered and supported to effectively fulfil its mandate in the digital age.

The dialogue reinforced a clear message that connectivity alone is not enough. Uganda must build an inclusive digital economy anchored in justice, transparency, and community voice. This means empowering watchdog institutions like the PDPO, updating outdated laws and regulations, investing in digital literacy, especially for youths and women, and supporting civic participation in digital policy-making.

In direct response, CIPESA launched the #BeeraSharp (translated as “Be Smart”) campaign. This initiative aims to equip Ugandan businesses with the knowledge and tools to act responsibly in the digital space. #BeeraSharp champions a culture of accountability, urging businesses to take charge of how they collect, store, share, and protect user data. It also promotes understanding of legal obligations under Uganda’s Data Protection and Privacy Act, while encouraging ethical digital conduct across sectors.

A Digital Future for All?

As Uganda ramps up its digitalisation agenda and embraces emerging technologies such as AI and robotics, businesses, policymakers, and civil society must work hand in hand to ensure Uganda’s digital revolution is not just a story of innovation but also a story of inclusion and respect for human rights. As the dialogue closed, one key takeaway stood out: Uganda’s digital future must be intentionally inclusive and rights-driven. Achieving this will require cross-sector collaboration to scale digital skills, reform of outdated laws, more financial and capacity support to institutions like UHRC, NITA-U and the PDPO to protect data rights, and empowering communities through digital literacy, local innovation, and inclusive governance.