Although the use of Information and Communication Technologies by citizens and governments in Africa is growing exponentially, there is limited evidence of how these technologies are affecting statebuilding and peace building on the continent. Where such evidence exists, it is often in diverse locations and hard to reach for researchers, practitioners, the media and government bodies.

In order to increase access to information on ICTs in Africa, the Centre for Global Communications Studies (CGCS) at the University of Pennsylvania has launched a new website that offers news and updates on research and events related to ICTs, peace building and governance. The portal features a repository of reports and articles with empirical evidence on the role of ICTs in peace building and governance.

In addition, the website offers access to articles typically blocked by journal paywalls by obtaining pre-print versions of articles from authors.

As a partner in CGCS’s project titled “Reframing Local Knowledge: ICTs, State building, and Peace building in Eastern Africa”, CIPESA undertook a review of literature on the role of ICTs in governance, peace-building and state-building in Africa, with a focus on three neighbouring countries: Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia.

An increasing number of Africa’s estimated one billion people are accessing modern communication technologies. According to the International Telecommunications Union, as of 2013, internet penetration stood at 16% and mobile access at 63% of Africa’s population.

It follows that online service provision, placing a wide array of information in the public domain, an empowered citizenry that holds leaders to account and smartly embrace ICT, could potentially catalyse peace, democracy and good governance in Africa.

There is a considerable amount of research by scholars, government agencies, civil society, development partners and many more on the use of ICTs in governance in Africa, covering a broad range of definitions and dimensions. A central place to find this research has hitherto been lacking, which is why scholars, practitioners and public officials will find the new portal a vital resource.

The work for the project is being carried out in collaboration with the Programme in Comparative Media Law and Policy (PCMLP) at the University of Oxford, the Centre for Intellectual Property and Information Technology at Strathmore University (Kenya), the School of Journalism and Communication at Addis Ababa University (Ethiopia), CIPESA, The Heritage Institute for Policy Studies and SIMAD University (Somalia).

Read more about the project here.

Towards an African Declaration on Internet Rights

As internet usage continues to grow in Africa, so does the interest by governments to monitor users’ online activities. This has led to a clash between internet rights promoters and governments in some African countries.

On February 12–13, 2014, participants from several African civil society organisations involved in promoting human rights and internet rights convened in Johannesburg, South Africa to draft an African Declaration on Internet Rights and Freedoms. The meeting was organised by the Association for Progressive Communications (APC) and Global Partners Digital in collaboration with the Media Rights Agenda, Media Foundation for West Africa and the Kenya Human Rights Commission.

Many countries justify their tough stance on internet freedom as necessary to fight cybercrime, promote peace and maintain national security. Whereas some of these policies and practices have been adopted by authoritarian regimes to retain power, others were in response to national crisis contexts such as hate speech and terrorism. Ultimately, the measures have often had chilling effects on access to information, freedom of expression, privacy and data protection.

Participants in this meeting called for the promotion of an open, free and accessible internet. Issues identified as the most crucial and still hindering internet growth in Africa that need immediate action were: improving access to internet including the development and promotion of localised multi-lingual content; addressing internet infrastructure obstacles; capacity building for users; and the need to create a balance between freedom of expression and privacy of users.

Others identified were data protection, addressing gender inequalities and gender-based violence against women online, and adopting supportive ICT policies that promote freedom of expression online and equitable access to information.

Due to increased internet freedom violation incidents coupled with regressive policies being made in many countries, the need for a well-defined Internet Intermediary Liability (ILL) regime has also become increasingly apparent. Another meeting held on February 10-11, 2014 organised by the APC with support from Google Africa discussed the responsibility that may be placed on intermediaries in implementing monitoring and control mechanisms laid down by the laws.

At the regional level, there are legal and regulatory frameworks like the Africa Charter on Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression in Africa, which provide limited protection for internet rights and the liability of internet intermediaries. It was noted that such frameworks could act as building blocks for individual countries to draw up best practices on ILL regimes.

There was consensus that such existing frameworks should be the basis for adopting a general guide with definitions of terms on Internet intermediary liability. This guide would act as central referencing document on which individual countries would base their national IIL regimes.

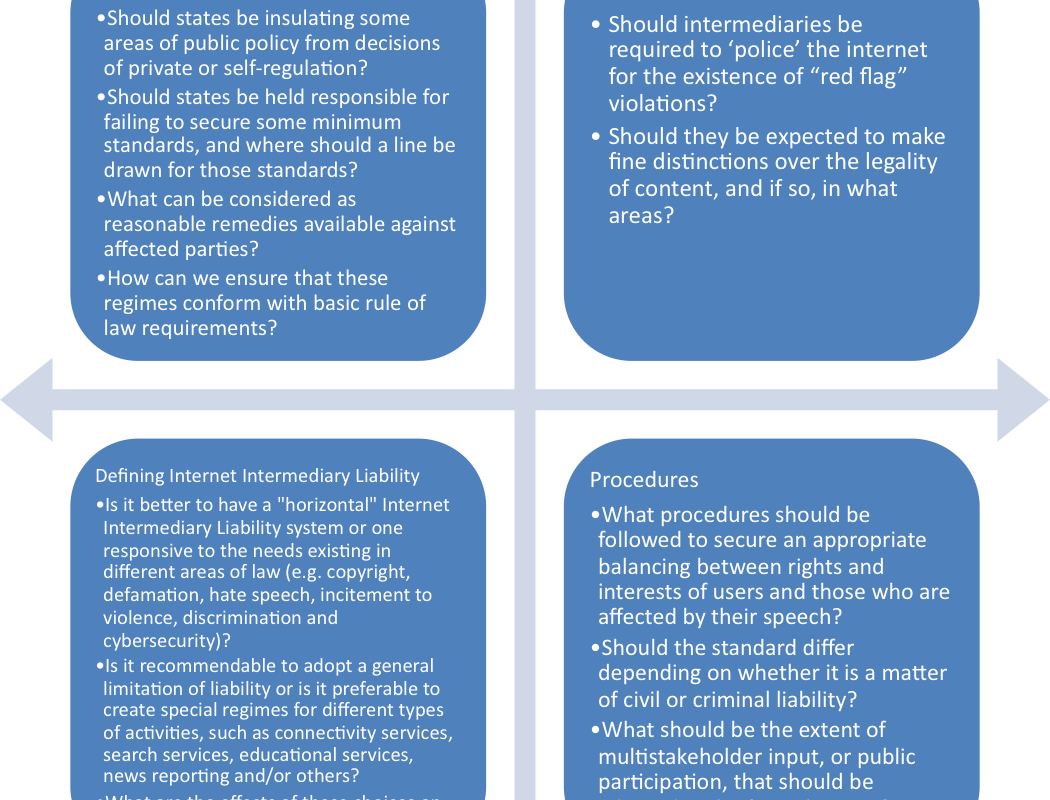

During the discussions, participants charted their thoughts on a best practice guide for an IIL regime for Africa by asking the below questions:

While responding to these questions, participants recognised that intermediaries can play a crucial role in promoting Internet freedoms in Africa.

Meanwhile, the meeting also reviewed recent policy and practice developments in Uganda, Kenya, South Africa and Nigeria since the 2011 Intermediary Liability in Africa research. It identified a need to increase awareness among different stakeholder groups of the importance of clear regulatory frameworks for intermediary liability to secure rights on the internet; and for stronger collaboration to advocate for best practice internet intermediary regulatory measures in Africa.

The outcomes of both these meetings will form the basis for the draft civil society Africa Declaration on Internet Rights and Freedoms, which will be launched at the ninth global Internet Governance Forum (IGF) in Istanbul, Turkey September 2-5, 2014. The declaration will be available for public input throughout the period leading up to IGF 2014.

Exploring The State of Internet Freedom in Africa

What is the price of security? Should it be your online freedom?

By Juliet Nanfuka

Where do human rights and online rights meet? Is there a clash between online freedom and human rights? Is there room for self-regulation? These are some of the questions that a recently concluded online discussions report on Internet freedom in Africa explores.

Participants from Uganda, Kenya and Nigeria used online platforms to discuss these issues over a four week period at the end of 2013.

A key theme that came out of the report is the recognition of the increased numbers of internet users across the continent and parallel to this, increased measures taken by governments on surveillance of citizens. This, in turn, has brought to the fore many questions about freedom of expression and privacy.

Many countries are faced with contradictory policies when it comes to freedom of expression especially when it is placed alongside national security and stability. As a result, freedom of expression is threatened by restrictive legal measures that infringe on the access and sharing of information. In addition to these are the legal permissions granted to governments with regards to accessing information about users. Requests from African governments, although few, appear to be politically motivated according to the Google Transparency Reports.

In light of this, a participant asked a key question that also raises concerns about censorship, “How much can you restrict if those with no restriction can interact with and pass on information to the restricted using alternative methods of communication?” This led to the recognition of the conflict that exists between online freedom of expression and the state. Such was seen in the 2011 politically motivated ‘Walk to Work’ protests in Uganda in which the national communications regulatory authority, the Uganda Communications Commission, instructed ISPs to block access to social networking sites like Twitter and Facebook for 24 hours. More on this can be found here Internet Freedom in Africa Under Threat.

The report, prepared by the Collaboration on International ICT Policy in East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) in partnership with Paradigm Initiative Nigeria (PIN) can be downloaded here.

CIPESA in 2014

In 2014, we continue to work to promote the inclusiveness of the information society. Under four thematic areas (Internet Governance, ICTs for Democracy, Online Freedoms and Open Data & eGovernance), our projects this year span 8 countries (Burundi, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Somalia, South Africa, Tanzania and Uganda). Highlights of our focus, activities and partners are summarised here.

Video: Introduction to eSociety Kasese

Located in Western Uganda, eSociety Kasese is a resource centre that promotes ICT literacy and the use of ICT for transparency in the local government. As part of its iParticipate Uganda project, the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) has provided to the centre equipment and connectivity support. In addition, we jointly conduct research and citizen journalism training.

Below is an introductory video to the Centre.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0gHmetwCgfo[/youtube]