Policy Brief |

Privacy is a fundamental human right guaranteed by international human rights instruments including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in its article 12 and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, in its article 17. Further, these provisions have been embedded in different jurisdictions in national constitutions and in acts of Parliament.

In Africa, regional bodies have invested efforts in ensuring that data protection and privacy are prioritised by Member States. For instance, in 2014 the African Union (AU) adopted the Convention on Cybersecurity and Personal Data Protection. In 2010, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) developed a model law on data protection which it adopted in 2013. Also in 2010, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) adopted the Supplementary Act A/SA.1/01/10 on Personal Data Protection Within ECOWAS. The East African Community, in 2008, developed a Framework for Cyberlaws. Notwithstanding these efforts, many countries on the continent are still grappling with enacting specific legislation to regulate the collection, control and processing of individuals’ data.

On May 25, 2018, the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) came into effect. The GDPR is likely to force African countries, especially those with strong trade ties to the EU, to prioritise data privacy and to more decisively meet their duties and obligations to ensure compliance.

See this brief on the Challenges and Prospects of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Africa, where we explore the consequences of GDPR for African states and business entities.

African Human Rights Commission Denounces Stringent Internet Regulation in East Africa

By Daniel Mwesigwa and Edrine Wanyama |

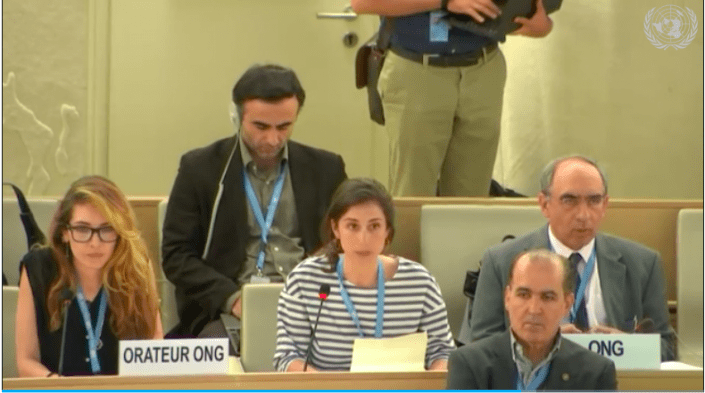

The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) has denounced moves by countries in East Africa to slap stringent regulations on internet access and use. The commission’s Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information in Africa, Lawrence Mute, and the Country Rapporteur responsible for monitoring the human rights situation in Kenya and Tanzania, Solomon Dersso, said in a statement that they wished to “express concern on the growing trend of States in East Africa adopting stringent regulation measures on the Internet and Internet platforms.”

Reminding the states of their obligations under continent-wide human rights instruments, the Commission urged them “to ensure that regulations do not undermine their commitment to ensure freedom of expression and access to information on the Internet and social media platforms.”

The Commission’s statement comes at a time when countries in the region are increasingly looking at the internet as a threat and using a series of strategies to curtail citizens’ access and use of digital technologies. In recent months, Tanzania, Uganda, and Kenya have appeared to read from the same script in curtailing freedom of expression and the free flow of information online.

Last April, Tanzania issued regressive regulations that require all online content providers including discussion forums, podcasters, bloggers, online radios and TVs to register at prohibitive costs prior to licensing. Enforcement of the regulations has resulted in suspension of bloggers and shutdown of some websites, while some social media activists have been arrested and threatened.

Meanwhile, Uganda has this month introduced tax on ‘Over-The-Top’ (OTT) services, which requires users to pay Uganda Shillings (UGX) 200 (USD 0.05) per day to access social media and other sites. The move has undermined affordability of the internet and, like an earlier March 2018 directive requiring online publishers, news platforms, radio and television operators to obtain authorization has been widely interpreted as an attempt by government to muzzle citizens’ voices online. Uganda’s president, Yoweri Museveni, has on several occasions accused social media users of peddling “lies” and “gossip”.

In May 2018, Kenya enacted the Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes Act, which human rights defenders contend contravenes constitutional provisions on freedom of opinion, freedom of expression, freedom of the media, and the right to privacy. Also, Kenya’s Film and Classification Board (KFCB) issued a directive requiring licenses for anyone interested in distributing or sharing video content on social media irrespective of whether captured using a professional camera or basic phone camera.

The full July 12, 2018 statement from the Commission, a body established in 1987 under the African Charter to protect and promote human and peoples’ rights throughout the continent is available here.

Uganda’s Social Media Tax Threatens Internet Access, Affordability

By Juliet Nanfuka |

Uganda’s president Yoweri Museveni has directed the finance ministry to introduce taxes on the use of social media platforms. According to him, the tax would curb gossip on networks such as WhatsApp, Skype, Viber and Twitter and potentially raise up to Uganda Shillings (UGX) 400 billion (USD 108 million) annually for the national treasury. The ministry has already proposed amendments to the Uganda Excise Duty Act, 2014 to introduce taxation of “over-the-top” (OTT) services, and raise taxes on other telecommunications services.

Section 4 of the Excise Duty (Amendment) Bill 2018, a copy of which was obtained by CIPESA, states: “A telecommunication service operator providing data used for accessing over the top services is liable to account and pay excise duty on the access to over the top services.” The amendment defines such services as the “transmission or receipt of voice or message over the internet protocol network and includes access to virtual network; but does not include educational or research sites which shall be gazetted by the Minister.”

According to the proposals, which could take effect on July 1, 2018, OTT services that commonly include messaging and voice calls via Whatsapp, Facebook, Skype and Viber will attract a tax duty of UGX 200 (USD 0.05) per user per day of access. In his letter, Museveni said the government needed resources “to cope with the consequences” of social media users’ “opinions, prejudices [and] insults”. He proposed a levy of UGX 100 (USD 0.025) per day per OTT user. Prime Minister Ruhakana Rugunda supported the suggestion as did the ICT minister, who stated that the taxes were meant to increase local content production and app innovation in Uganda.

If implemented, the proposed tax will be the latest in a series of government actions that threaten citizens’ access to the internet. Last month, the communications regulator issued a directive calling for registration of online content providers and also released tough restrictions on registration of SIM cards. At the USD 0.05 per day suggested by the finance ministry, a Ugandan user would need to fork out USD 1.5 per in monthly fees to access the OTT services. That would be hugely prohibitive since the average revenue per user (ARPU) of telecom services in Uganda stands at a lowly USD 2.5 per month.

According to the Uganda Communications Commission (UCC), in the 2016-2017 financial year, Uganda’s telecommunications sector contributed UGX 523 billion (USD 141.2 million) to national tax revenue, an increase of 14.3% from the previous year’s UGX 458 billion (USD 123.6 million).

As of September 2017, Uganda had an internet penetration rate of 48% while the mobile subscription stood at 65 lines per 100 persons. Research shows that at least one in nine internet users in the country is signed up for a social networking site, with Facebook and WhatsApp the most popular.

Indeed, social media and by extension OTT services, are key avenues for public discourse, service delivery and political engagement. As per the recently released results of the national IT survey 2017/18, 92% of MDAs have a social media presence with most using Facebook, Twitter and WhatsApp as their primary platforms for information dissemination and engagement with citizens. Meanwhile, telecommunications companies have tapped into the popularity of OTTs by offering competitive social media data packages, resulting in what was popularly referred to as “data price wars.”

The amendment bill also proposes a 12% tax for airtime on cellular, landline and public payphones. The latter two previously attracted a 5% tax. The tax on mobile money transfers has been increased from 10% to 15%, while a 1% tax has been introduced to the value of mobile money transactions of receiving and withdrawals.

The proposed taxes do little to support internet affordability in Uganda, which already scores poorly on the Affordability Drivers Index (ADI) that annually assesses communications infrastructure, access and affordability indicators. Currently, 1GB of mobile prepaid data in Uganda costs more than 15% of the average Ugandan’s monthly income. This is much higher than the recommended no more than 2% in order to enable all income groups to afford a basic broadband connection.

The proposed taxes have also raised considerable debate among members of civil society and the business sector, who are concerned that consumers will inevitably be economically affected, while the legal fraternity has called the move unconstitutional. In a country where two social media shutdowns were ordered in a space of three months during 2016, and where some social media users have been prosecuted or arrested over opinions expressed on Facebook and Twitter critical of public officials, these developments are particularly worrying. Already, the perceived high level of surveillance has forced many Ugandans including the media, into self-censorship, turning them away from discussing “sensitive” matters of community or national importance.

The increasing popularity of social media enabled OTT services, brings new regulatory challenges for governments, as many of these services have not required a licence or been required to pay any licensing fee according to the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF). However, the regulation of OTT platforms and services may in some cases adversely affect user rights.

On the financial inclusion front, the proposed taxes are also likely to affect mobile money subscriptions and the cost of doing business. In Uganda and across Africa, mobile money has become the primary means of financial transactions, offering new opportunities for productivity and efficiency gains to governments, businesses and individuals.

Feature photo by GotCredit

Tanzania Issues Regressive Online Content Regulations

By Ashnah Kalemera |

Tanzania has issued online content regulations that oblige bloggers, owners of discussion forums, as well as radio and television streaming services to register with the communications regulator and to pay hefty licensing and annual fees.

There are three types of licences. A license for provision of online content services comes at an initial cost of TZShs 1.1 million (USD 484) comprised of an application fee of USD44 and an initial licencing fee of USD 440. In addition, there is an annual licence fee of USD440, and a similar amount has to paid for licence renewal after three years.

A licence to stream radio or television content on the internet costs TZShs 250,000 (USD110), with annual licence fees set at USD 88. This licence also has to be renewed after three years at a cost of USD 88.

The Electronic and Postal Communications (EPOCA) (Online Content) Regulations, 2018, which were issued on March 13, 2018, join a catalogue of legislation related to online content in Tanzania that threatens citizens’ constitutionally guaranteed rights to privacy and freedom of expression. The regulations are also likely to negatively impact on an already fragile intermediary liability landscape in a country fraught with increasing media repression and persecution of government critics.

When the Tanzania Communications Regulatory Authority (TCRA) initially published the draft regulations last September, they did not have the requirement to apply for online content service licences as set out in Regulation 14 of the enacted regulations. It states: “Any person who wishes to provide online content services shall fill in an application form as prescribed in the First Schedule and pay fees as set out in the Second Schedule to these Regulations.”

Applicants are required to provide their company details including physical address, shareholding, citizenship of shareholders/directors and tax registration. The communications regulator, TCRA, has the right to cancel licences over non-compliance.

The regulations that have been issued are more regressive than the draft which the regulator issued in September 2017 for public comment.

See CIPESA’s full analysis of the draft EPOCA Content Regulations, 2017 – available in English and Swahili.

Under obligations of internet cafes, the final regulations introduced two clauses that threaten user privacy. Under regulation 9, café owners are required “to ensure that all computers used for public internet access are assigned public static IP addresses”. This could inhibit the use of circumvention tools such as Virtual Private Networks (VPN) that rely on dynamic IP address protocols, and which citizens resorted to using in neighbouring Uganda during state-initiated interruptions to communications.

Further, the regulations extend café owners’ obligations to install camera equipment to include registration of users “upon showing a recognised identity card”. Pursuant to regulation 9(2), recorded surveillance and the user register “shall be kept for a period of twelve months.”

Several regressive provisions from the draft version were also passed. Regulation 6(1) requires licenced service providers who provide online content or facilitate online content production to terminate or suspend subscriber accounts and remove content if found in contravention of the regulations, within 12 hours from the time of notification by TCRA or by an affected person. This requirement places a heavy technical and human resource burden on content hosts and providers to have in place competencies to handle complaints within 12 hours.

Swift content restriction or removal is also required of online content hosts under regulation 8(b) and content providers and users under regulation 5(1)(g). As we argued in an earlier brief, while content such as revenge pornography and that which promotes violent extremism may be justifiably removed promptly, there is a danger that the regulations may be applied unjustifiably to content such as that relating to exposure of corruption or human rights violations.

Whereas regulation 16 provides for a complaints handling procedure, the regulations do not provide for the process nor mechanisms for legal recourse over contested content.

Regulation 5(1)(e) requires content providers to “have in place mechanisms to identify source of content”. This obligation poses a threat to the right to anonymity and whistleblowing and may lead to self-censorship.

Moreover, Regulation 12 on content prohibited from publication lists restrictions with broad definitions and which have potential to limit freedom of expression. In terms of scope, it includes unspecified content that “causes annoyance”; “uses disparaging or abusive words which is calculated to offend an individual or a group of persons”; and is “crude”, “obscene” or “profane” including in local languages.

Regulation 12 also prohibits publication of “false content which is likely to mislead or deceive the public except where it is clearly pre-stated that the content is i) satire and parody ii) fiction; and iii) where it is preceded by a statement that the content is not factual.”

Nonetheless, the regulations have some positive elements, among them regulation 10(b) which requires users to use device passwords to ensure that unscrupulous and unauthorized persons do not access their social media accounts.

The requirement for provision of easily accessible user terms and conditions by licensed service providers, adoption of a code of conduct for content hosting, and publication of a safe internet use policy for internet cafes, are also commendable in promoting user awareness of platform policies. The regulations also provide important safeguards for child protection online, such as regulation 13 which prohibits children’s to access to prohibited content online.

In a boost to privacy and data protection, regulation 11 prohibits unauthorised disclosure of “any information received or obtained” under the provisions of the regulations, except where the information is required for law enforcement purposes. Furthermore, regulation 11 restricts use of information only to the “extent” that is “necessary for the proper performance of official duties.” Nonetheless, in the absence of data protection and privacy legislation in Tanzania, these safeguards could be rendered of little value and hence prone to abuse.

It remains to be seen how the new regulations will be enforced and how they will impact on citizens’ rights online. However, given Tanzania’s history of predatory action against internet users following the enactment of the Cybercrime Act, 2015, the new regulations are likely to be utilised to further undermine the internet freedom situation in the country.