FIFAfrica |

The Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) is pleased to announce the 12th edition of the annual Forum on Internet Freedom in Africa (#FIFAfrica25)—the continent’s leading platform for shaping digital rights, inclusion, and governance conversations. This year, the Forum is headed to Windhoek, Namibia, a beacon of press freedom, gender equity, and progressive jurisprudence, and will take place on September 24–26, 2025.

Namibia ranks highest in Africa on global press freedom indices and is equally highly ranked on the Freedom in the World index, where it is categorised as Free. In 2025, it made history with women at the helm of the Presidency, Vice Presidency, and National Assembly, a key moment for gender inclusion and in the country’s political landscape. The country has made considerable efforts to uphold public rights such as through rejecting efforts by the Central Intelligence Service to block reporting on corruption; ruling against the unconstitutional collection of telecom revenue, and reinforcing legal safeguards in digital regulation. While outdated laws still pose challenges and a data protection bill is pending, Namibia is actively updating its legal frameworks.

It is against this backdrop that FIFAfrica25 will delve into the evolving digital landscape in Africa and cast a light on the most pressing internet freedom issues today. The Forum offers a unique, multi-stakeholder platform where key stakeholders, including policymakers, journalists, global platform operators, telecommunications companies, regulators, human rights defenders, academia, and law enforcement representatives convene to deliberate and craft rights-based responses for a resilient and inclusive digital society for Africans.

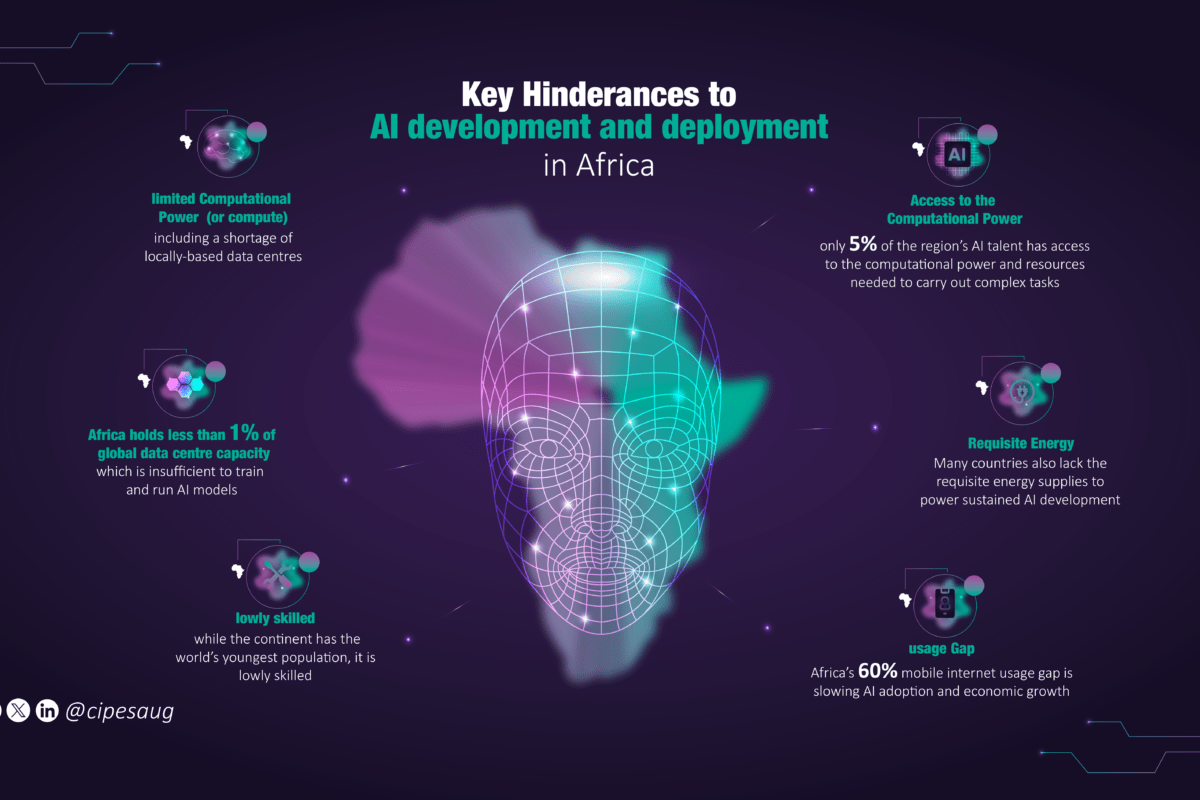

As digital technologies shape Africa’s political, economic, and social landscape, safeguarding digital rights is essential to building inclusive, participatory, and democratic societies. Key themes at FIFAfrica25 will include:

- AI, Digital Governance, and Human Rights

- Disinformation and Platform Accountability

- Internet Shutdowns

- Digital Inclusion

- Digital Trade in Africa

- Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI)

- Digital Safety and Resilience

The Forum will also serve to gather insights that will shape Africa’s voice in global digital governance processes like WSIS+20 and the Global Digital Compact. These global processes represent critical opportunities for African voices to influence the emerging digital and AI governance agendas. Additionally, the 2025 edition of the annual State of Internet Freedom in Africa report will be launched.

Get Involved with FIFAfrica25

Over the years, the Forum has been co-hosted with various government ministries, regional and national partners, and a vibrant network of collaborators. Together, this community have made FIFAfrica come alive over the years and illustrated a commitment towards building an inclusive digital rights ecosystem. This network of actors committed to have also supported the growth and evolution of the Forum.

Partner with us, host a side event, or support the participation of individuals who might otherwise be unable to attend the Forum. See more about becoming an ally or supporter here.

About FIFAfrica

FIFAfrica25 will be the third edition to be hosted in Southern Africa. Previous editions have been hosted in Uganda, South Africa, Ghana, Ethiopia, Zambia, Tanzania and Senegal. The Forum objectives include the following:

- Enhance Networking and Collaboration: Provide a platform that assembles African thought leaders and networks working on internet freedom from diverse stakeholder groups.

- Promote Access To Information: Since its inception, FIFAfrica has commemorated September 28, the International Day for Universal Access to Information (IDUAI), creating awareness about access to information offline and online and its connection to wider freedoms and democratic participation.

- Practical Skills and Knowledge Development: The Forum features pre-event practical training workshops for various stakeholders on a range of internet freedom issues, including technical aspects of internet access, policy developments, digital resilience, and advocacy strategies.

- Showcase Advocacy Efforts: Provide a space for entities advancing digital rights to showcase their work through artistic installations, photography, reports, interactive platforms and physical stalls with organisational representatives.

- Connect Research to Policy Discussions: The annual State of Internet Freedom in Africa report, a themed report produced by CIPESA, has been launched at FIFAfrica since 2014. The report has served to inform policy and advocacy efforts around the continent.

- Strategic Networks: Serve as a platform for strategic meetings to be held, offering various African and global networks the opportunity to directly engage with each other and with the extended digital rights community.