As internet usage continues to grow in Africa, so does the interest by governments to monitor users’ online activities. This has led to a clash between internet rights promoters and governments in some African countries.

On February 12–13, 2014, participants from several African civil society organisations involved in promoting human rights and internet rights convened in Johannesburg, South Africa to draft an African Declaration on Internet Rights and Freedoms. The meeting was organised by the Association for Progressive Communications (APC) and Global Partners Digital in collaboration with the Media Rights Agenda, Media Foundation for West Africa and the Kenya Human Rights Commission.

Many countries justify their tough stance on internet freedom as necessary to fight cybercrime, promote peace and maintain national security. Whereas some of these policies and practices have been adopted by authoritarian regimes to retain power, others were in response to national crisis contexts such as hate speech and terrorism. Ultimately, the measures have often had chilling effects on access to information, freedom of expression, privacy and data protection.

Participants in this meeting called for the promotion of an open, free and accessible internet. Issues identified as the most crucial and still hindering internet growth in Africa that need immediate action were: improving access to internet including the development and promotion of localised multi-lingual content; addressing internet infrastructure obstacles; capacity building for users; and the need to create a balance between freedom of expression and privacy of users.

Others identified were data protection, addressing gender inequalities and gender-based violence against women online, and adopting supportive ICT policies that promote freedom of expression online and equitable access to information.

Due to increased internet freedom violation incidents coupled with regressive policies being made in many countries, the need for a well-defined Internet Intermediary Liability (ILL) regime has also become increasingly apparent. Another meeting held on February 10-11, 2014 organised by the APC with support from Google Africa discussed the responsibility that may be placed on intermediaries in implementing monitoring and control mechanisms laid down by the laws.

At the regional level, there are legal and regulatory frameworks like the Africa Charter on Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression in Africa, which provide limited protection for internet rights and the liability of internet intermediaries. It was noted that such frameworks could act as building blocks for individual countries to draw up best practices on ILL regimes.

There was consensus that such existing frameworks should be the basis for adopting a general guide with definitions of terms on Internet intermediary liability. This guide would act as central referencing document on which individual countries would base their national IIL regimes.

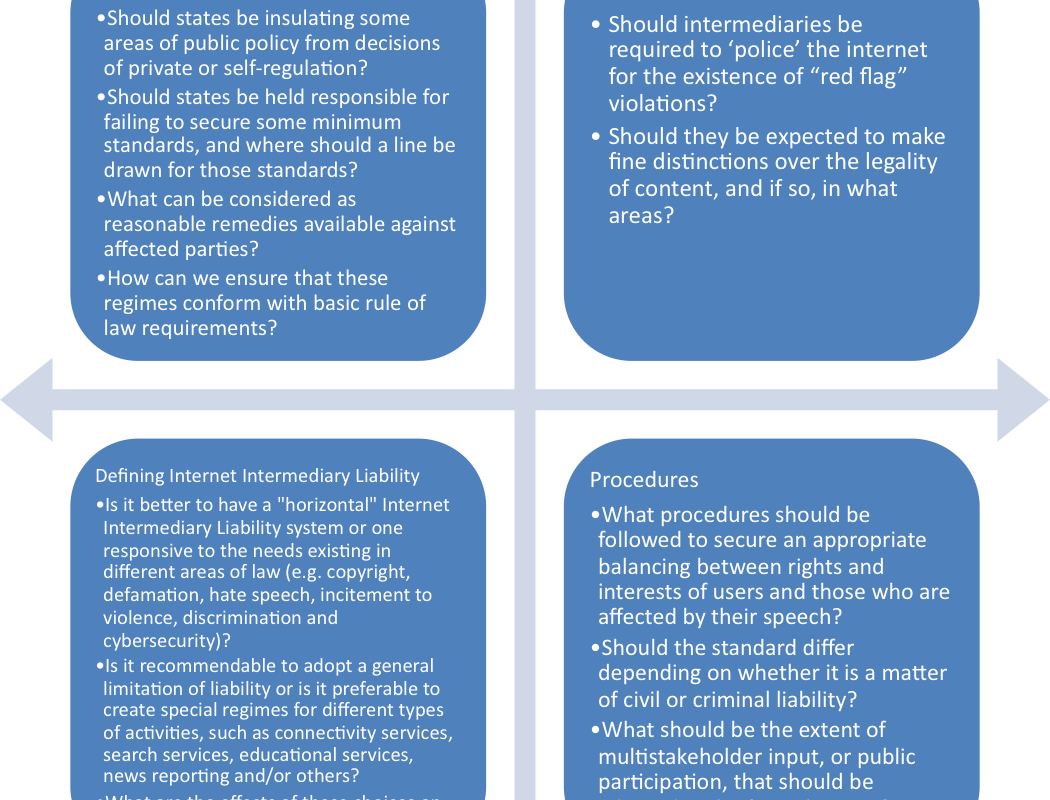

During the discussions, participants charted their thoughts on a best practice guide for an IIL regime for Africa by asking the below questions:

While responding to these questions, participants recognised that intermediaries can play a crucial role in promoting Internet freedoms in Africa.

Meanwhile, the meeting also reviewed recent policy and practice developments in Uganda, Kenya, South Africa and Nigeria since the 2011 Intermediary Liability in Africa research. It identified a need to increase awareness among different stakeholder groups of the importance of clear regulatory frameworks for intermediary liability to secure rights on the internet; and for stronger collaboration to advocate for best practice internet intermediary regulatory measures in Africa.

The outcomes of both these meetings will form the basis for the draft civil society Africa Declaration on Internet Rights and Freedoms, which will be launched at the ninth global Internet Governance Forum (IGF) in Istanbul, Turkey September 2-5, 2014. The declaration will be available for public input throughout the period leading up to IGF 2014.

Exploring The State of Internet Freedom in Africa

What is the price of security? Should it be your online freedom?

By Juliet Nanfuka

Where do human rights and online rights meet? Is there a clash between online freedom and human rights? Is there room for self-regulation? These are some of the questions that a recently concluded online discussions report on Internet freedom in Africa explores.

Participants from Uganda, Kenya and Nigeria used online platforms to discuss these issues over a four week period at the end of 2013.

A key theme that came out of the report is the recognition of the increased numbers of internet users across the continent and parallel to this, increased measures taken by governments on surveillance of citizens. This, in turn, has brought to the fore many questions about freedom of expression and privacy.

Many countries are faced with contradictory policies when it comes to freedom of expression especially when it is placed alongside national security and stability. As a result, freedom of expression is threatened by restrictive legal measures that infringe on the access and sharing of information. In addition to these are the legal permissions granted to governments with regards to accessing information about users. Requests from African governments, although few, appear to be politically motivated according to the Google Transparency Reports.

In light of this, a participant asked a key question that also raises concerns about censorship, “How much can you restrict if those with no restriction can interact with and pass on information to the restricted using alternative methods of communication?” This led to the recognition of the conflict that exists between online freedom of expression and the state. Such was seen in the 2011 politically motivated ‘Walk to Work’ protests in Uganda in which the national communications regulatory authority, the Uganda Communications Commission, instructed ISPs to block access to social networking sites like Twitter and Facebook for 24 hours. More on this can be found here Internet Freedom in Africa Under Threat.

The report, prepared by the Collaboration on International ICT Policy in East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) in partnership with Paradigm Initiative Nigeria (PIN) can be downloaded here.

Civil Society’s Proposals on The African Cybersecurity Convention

In December 2013, the Kenya ICT Action Network (KICTANet) led online discussions on the proposed African Union Convention on Cyber Security (AUCC). The convention establishes a framework for cyber security in Africa “through organisation of electronic transactions, protection of personal data, promotion of cyber security, e-governance and combating cybercrime.”

Civil society and academia have raised concerns about some of the articles in the convention, which had earlier been expected to be signed in January 2014. Latest reports indicate that, at the earliest, the law could be signed in June this year.

The report on the discussions will be used by KICTANet and partners such as CIPESA to create awareness and lobby African governments to pass legislation and instruments that fully support the privacy of individuals and the fully enjoyment of their freedom of expression online.

The stated background to the convention is that the African Union is seeking ways to intensify the fight against cybercrime across the continent“in light of the increase in cybercrime, and the lack of mastery of security risks by African countries.”

Furthermore, the AU states that a major challenge for African countries is the lack of adequate technological security to prevent and effectively control technological and informational risks. As such, it adds, “African States are in dire need of innovative criminal policy strategies that embody States, societal and technical responses to create a credible legal climate for cyber security”.

The intentions may be legitimate but, as noted by the online discussions, some of the articles in the current version of the convention could be used to negate individuals’ privacy and their right to express themselves through online mediums.

Take, for example, Article III – 34. It states that AU member states have to “take necessary legislative or regulatory measures to set up as a penal offense the fact of creating, downloading, disseminating or circulating in whatsoever form, written matters, messages, photographs, drawings or any other presentation of ideas or theories of racist or xenophobic nature using an a computer system.”

How does this clause balance with the fundamental right to freedom of expression? Experts argue that this clause is problematic as it requires a measure of truth, which is hard to actually legislate or determine owing to the relativity of truth. They add that this sort of law would likely be unenforceable.

The discussion noted that although African countries needed legal framework on cybercrime, the current proposals need numerous amendments. The discussions also noted a need for the African Union Commission to engage with civil society to draw up progressive and enforceable laws. However, civil society had the added task of creating awareness and capacity among citizens on cyber security and the need to uphold freedoms of expression online.

These discussions were conducted on multiple lists of KICTANet and the Internet Society (ISOC) Kenya and on the I-Network and ISOC Uganda ists moderated by the Collaboration on International ICT Policy in East and Southern Africa (CIPESA), from 25 – 29, November 2013. They were also shared through numerous pan-Africa and global lists on ICT policy and online freedom.

Download the full discussions report here.

Internet Rights in Uganda: Challenges and Prospects Workshop Report

The Collaboration on International ICT Policy in East and Southern Africa (CIPESA, www.cipesa.org) in conjunction with Unwanted Witness Uganda (www.unwantedwitness.or.ug) on November 28, 2013 organised a workshop on promoting internet rights in Uganda. The workshop aimed to create awareness among civil society, netizens, and the media in Uganda on how policy and practice affect internet freedoms in the country. The workshop also sought to draw up strategies for network building and advocacy to promote and protect online freedoms in Uganda.

Download the workshop report here.

Q&A: Uganda Government Develops Social Media Guidelines

The internet and indeed social media plays a key role in improving communication between citizens, government-to-government interactions and at government-to-citizen level. Social media, such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Instagram and MySpace, has the potential to improve governance and democracy practices.

Accordingly, the Uganda government through the National Information Technology Authority Uganda (NITA-U) has developed guidelines to “to facilitate secure usage of social media (Facebook and Twitter etc.) for efficient exchange of information across Government Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs) as well as improving effectiveness of communication, sharing of information and open engagement and discussions with the public.”

On November 28, 2013 Leonah Mbonimpa, the Corporate Communications Officer at NITA-U spoke to CIPESA about the thinking behind the guidelines.

Q. What is the background to developing these guidelines?

A. Government has decided to utilise new channels to communication such as social media to communicate to citizens and give timely responses to emerging issues. In this vein, NITA-U was requested to develop guidelines to help government agencies to embrace social media while maintaining the same level of decorum as with traditional media.

Q. Why did the government find it necessary to draw up these guidelines?

A. Traditionally, Government agencies have been communicating through accounting officers such as Permanent Secretaries. The advent of new media channels and the quest for speedy provision of information has necessitated the shift from traditional approaches to more flexible ways of communicating, [such as] using social media. Given that social media is relatively new and comes with a higher degree of responsibility when communicating, it was necessary to provide guidelines for government agencies to ensure that we communicate [appropriately].

Q. What do the guidelines intend to achieve?

A. They intend to achieve uniformity in communicating and ensure appropriate consultation is made before posting government communication online.

Q. How is users’ privacy protected in these guidelines?

A. The guidelines do not infringe on user privacy. They only seek to standardise the government’s approach to communicating to citizens online.

Q. Are there other initiatives in place or under development by government to protect freedom of expression and privacy online.

A. NITA-U is in preparatory stages of drafting a Data Privacy bill which will eventually be enacted into law to comprehensively address privacy issues.

Further details about the guidelines are available here http://www.nita.go.ug/index.php/features/315-socialmediguide