By Ashnah Kalemera |

From domestic work, ride hailing, content moderation, and delivery services, to sex work, technology has revolutionised employment and labour across the world. In Africa, according to a 2023 report by the World Bank, between 2016 and 2020, job postings on one of the largest digital labour platforms more than doubled. This demand on the continent is expected to grow over the coming years.

These new forms of labour and employment have generally advanced inclusion in the workforce and promoted economic empowerment. However, despite the existence of initiatives such as SheWorks! that are dedicated to engaging women in online work, the promise of new skills, flexibility and income, the potential of women’s participation in digital work has not been fully realised. For instance, in South Africa, the share of women in online work (52%) is growing but still less than in similar occupations in the workforce at large (61%).

Documented barriers to African women’s participation in online work include the gender digital divide and uneven access to the internet and digital tools. Meanwhile, the wider challenges of digitalisation of work and labour, including the lack of social protections, job insecurity, unequal pay, unfair treatment, discrimination, bias, increased surveillance and lack of autonomy, are exacerbated for women.

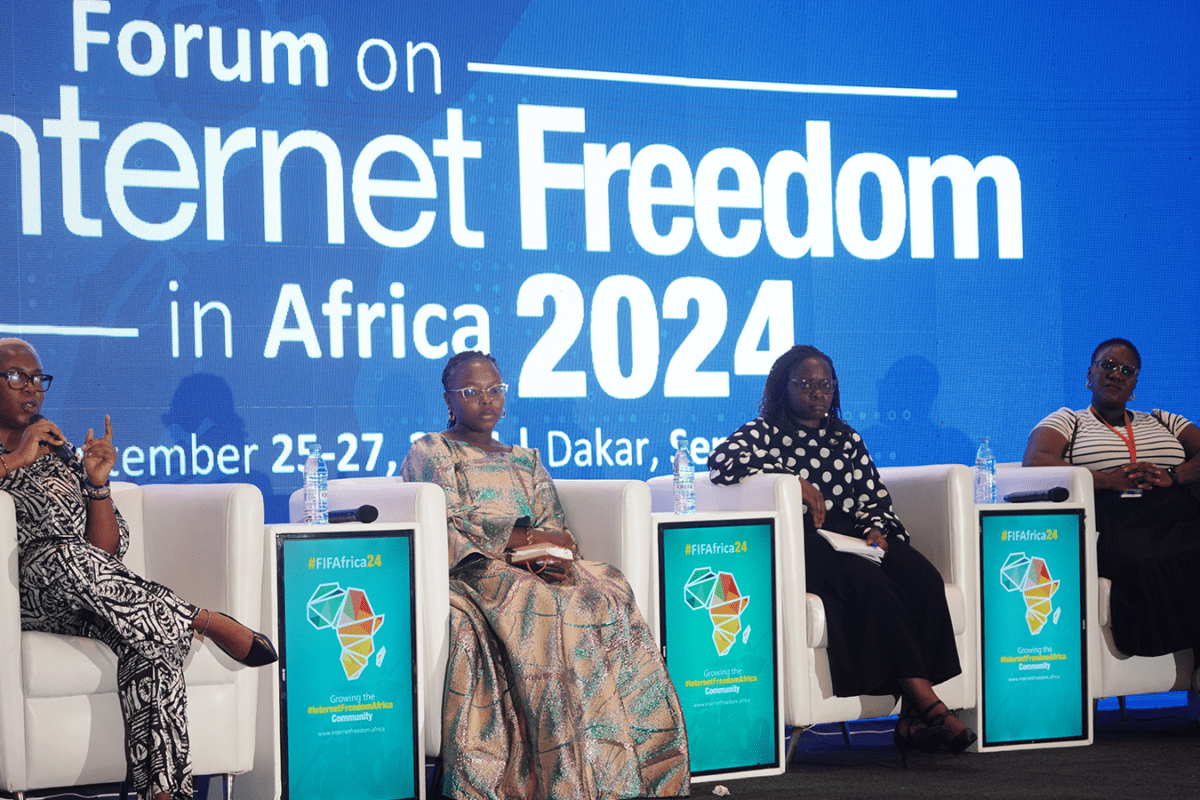

In an effort to build narratives and movements on gender and labour online, the recently concluded Forum on Internet Freedom in Africa 2024 (FIFAfrica24) featured discussions on feminist futures of work that highlighted lived experiences and advocacy strategies.

Speaking at the Forum, Abigail Osiki, a Lecturer in the Department of Mercantile and Labour Law at the University of Western Cape, South Africa, stated that fair and decent work for women online not only encompasses security, fair wages and productivity, but also mental health. The mental health challenges of online employment opportunities for women were said to be compounded by stigmas about certain forms of labour – such as sex work being considered prostitution and virtual assistants being “just secretaries”.

“The worst part about working for OnlyFans for me is the toll it takes on my mental health. For a long time I kind of swallowed my emotions and didn’t care what anyone thought because I was making so much money, but then it got to a point where I felt like I was selling my soul. I would often break down to my younger brother that I feel like I sold my soul.” – an Interview with an OnlyFans Worker.

The “uneven power” within online employment was also pointed out. Highlighting the example of non-disclosure agreements (NDAs), speakers at FIFAfrica24 argued that such agreements perpetuated “master-servant relationships” and “forced labour”, leaving many women with no option but to work “from a point of desperation as opposed to choice”.

A former content moderator for a social media platform narrated her recruitment as a language translator, signing of an NDA, and only finding out the scope of her work upon exposure to graphic content. She recalled the mental health side effects of the job and the inability to disclose the nature of her work to healthcare professionals for “fear of going to jail for 20 years” as stipulated in the NDA. She added that she worked in a foreign country without a work permit for a year, isolated in a hotel for six months and without leave days. Whereas she and colleagues were able to unionise, they had no legal support. The unionisation initially led to salary increments but their employment contracts were later terminated without benefits.

For African women in the informal sector, the situation was said to be even more dire. As part of her address in the opening ceremony, Catherine M’seteka of the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF) argued that limited access to information and digital illiteracy had made it harder for domestic workers to mobilise or report common violations such as forced labour, exploitation and sexual harassment.

According to Siasa Place’s Angela Chukunzira, digitalisation also had an impact on non-tech based labour. She cited the example of online reviews in the hospitality sector and their impact on the rights of housekeeping workers – who are usually women.

“Marginalised workers are invisible in policy making,” said M’Seteka as she called for more platforms – both formal and informal – for multi-stakeholder engagement and advocacy on the digital economy.

M’Seteka’s and others’ calls echo recommendations in a policy brief on Labour and Digital Rights in Africa, which emphasised the need to strengthen legal recognition of workers online to ensure their safety and welfare alongside efforts to foster innovation and economic growth that overcome inequalities, bias and discrimination.

In visioning a future of work from a feminist perspective, Osiki stated that advocacy and policy interventions must consider women in the digital workforce as heterogeneous – of different cultures, contexts and involved in different types of work. That way, regulation of uneven power relations and efforts in collective bargaining would articulate varied interests to avoid exploitation. Priorities put forward for collective bargaining were equal pay, contract transparency, protection against harassment and exploitation, alongside career mobility and progression as well as health and safety. “All these [interests] vary for freelancers, domestic workers, location-based service providers and content moderators,” said Osiki.

African states were urged not to politicise technology-based jobs as a solution to the continent’s unemployment and poverty crisis. Rather, they should negotiate partnerships and equitable regulation with a view of increasing tax revenue to enable provision of social and welfare protections for citizens.

For the wider community – users, activists, media, the legal fraternity and civil society organisations – there were calls for solidarity such as in strategic litigation and establishing communities of care to support women in digital workspaces. This, together with efforts to promote cultural and language sensitivity for some forms of employment would go a long way in overcoming derogatory and biased narratives in society.