Our first convening of thought leaders and internet freedom enthusiasts took place in September 2014 in Kampala, Uganda. Over the course of one day, 80 participants from 6 countriesdebated the polices affecting internet freedom in East Africa. In 2015, the number of participants more than doubled,while the Forum span two days and included a wider range of topics for discussion. In 2016, we expanded on the topics of discussion following contributions madeby an online call. We added a training workshop on human rights and internet policy, and hosted digital security clinics. The 2016Forum hadthe most diverse audience to-date with 240 participants representing 24 countries.

Our first convening of thought leaders and internet freedom enthusiasts took place in September 2014 in Kampala, Uganda. Over the course of one day, 80 participants from 6 countriesdebated the polices affecting internet freedom in East Africa. In 2015, the number of participants more than doubled,while the Forum span two days and included a wider range of topics for discussion. In 2016, we expanded on the topics of discussion following contributions madeby an online call. We added a training workshop on human rights and internet policy, and hosted digital security clinics. The 2016Forum hadthe most diverse audience to-date with 240 participants representing 24 countries.FIFAfrica serves as a convening of tech actors, academia, the private sector, curious citizens, the creative industry, and thought leaders from various backgrounds to track the path that internet freedom is taking and to find ways in which to address gaps in policy and implementation. Ultimately, the Forum serves to create meaningful relationships within the continent with the goal of realising more progressive policy development and an inclusive online community that is guided by global best practice and frameworks such as the African Declaration on Internet Rights and the Sustainable Development Goals. The Forum also serves as an opportunity to kickstart conversations that feed into national, regional and global discussions on internet governance and human rights including Internet Governance Forums at regional and national levels, RightsCon and the Stockholm Internet Forum, among others.

At the core of every Forum is the launch of the annual State of Internet Freedom in Africa report. As the Forum has grown, so has the number of countries in which we undertake in-depth analysis on internet freedom.In the 2014 report, we featured seven countries - Burundi, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda. In 2016, The report covered nine countries –Burundi, Democratic Republic of the Congo (English, French), Ethiopia, , Somalia, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

FIFAfricadates coincide with the commemoration of International Day for Universal Access to Information (IDUAI) on September 28thas access to information and freedom of expression are inextricably linked both online and offline.

We appreciate the support of our partners whodedicate time and resources towards the Forum and continue to play a vital role in promoting a free, safe and open internet.

In this report we share some insights from proceedingsat the 2016 Forum.

CIPESA Team

Join the conversation: #InternetFreedomAfrica

See the Forum on Internet Freedom in Africa 2016 Highlights

Forum on Internet Freedom in Africa 2017

In 2017, we aim to deliver another Forum on Internet Freedom in Africa that recognises the work and contributions of various internet governance players across the continent and indeed creates collaborations that can strengthen privacy, access to information, free expression, non-discrimination and the free flow of information online.in Africa.

Here is how you can support the Forum on Internet Freedom in Africa 2017

- Proposea session (Panel discussion/ side event/ Lightening Talk/ Skills Workshop) |

- Support the travel of participants from across the continent

- If you are interested in supporting the Forum, email us on [email protected]

Follow @cipesaug | Visit the Forum page

As a prelude to the Forum on Internet Freedom in Africa, CIPESA alongside the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and Paradigm Initiative Nigeria (PIN) hosted a two-day workshop on Human Rights and Internet Policy which was attended by Ugandan journalists and civil society organisations. A total of 40individuals participated at the workshop, including 30 journalists based beyond the capital, Kampala. These were drawn from media houses in Lira and Gulu (Northern Uganda), Fort Portal and Kabale (Western Uganda), as well as Jinja, Tororo, Soroti and Mbale (Eastern Uganda).

As a prelude to the Forum on Internet Freedom in Africa, CIPESA alongside the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and Paradigm Initiative Nigeria (PIN) hosted a two-day workshop on Human Rights and Internet Policy which was attended by Ugandan journalists and civil society organisations. A total of 40individuals participated at the workshop, including 30 journalists based beyond the capital, Kampala. These were drawn from media houses in Lira and Gulu (Northern Uganda), Fort Portal and Kabale (Western Uganda), as well as Jinja, Tororo, Soroti and Mbale (Eastern Uganda).The workshop entailed narration of the evolution and concepts of human rights alongside discussion on the guiding principles and sources of these fundamental rights. Participants went on to explore and discuss the mechanisms for the protection of human rights which include International and regional frameworks.These sessions were presented by Andrew Akutu and Javier Sanjuan, both of OHCHR.

We have 4 human rights mechanisms--treaties, human rights council, extra conventional mechanism + universal periodic reviews #FIFAfrica16

— CIPESA (@cipesaug) September 26, 2016

Discussion was brought closer to home with an in-depth exploration of the law making process in Uganda, and the status of freedoms in the country, including the right to freedom of expression and access to information. It emerged that these rights areinfringed upon offline and online, such as through internet shutdowns and the confiscation of equipment. Guest speaker Peter Magellah of Chapter Four Uganda, explained the laws that hinder freedom of expression in Uganda, noting that while the country’s constitution safeguards freedom of expression, over the years this right has been consistently infringed upon.

Interesting discussion on the role of ICT in enhancing democracy. Follow the discussion at #FIFAfrica16 https://t.co/UZwEQS61D2

— Evelyn Lirri (@Elirri) September 25, 2016

There were also discussionson the intersection of human rights and technology through three themes –defining internet freedom, the actors in internet freedom and, Africa and the Internet Freedom ecosystem. These were presented byGbengaSesan and AdeboyeAdegoke of PIN who presented on how these themes advance rights both online and offline including enabling civic participation. Juliet Nanfuka of CIPESA went onto connect these concepts to discussions onthe gap in ICT policy and the role of media in addressing these.

The best language comes from those who are most affected: #NetRightsNG - a citizen initiated law on online rights #FIFAfrica16 @pinigeria

The best language comes from those who are most affected: #NetRightsNG - a citizen initiated law on online rights #FIFAfrica16 @pinigeria

— CIPESA (@cipesaug) September 25, 2016

@Mose_Karanja of @StrathCIPIT: "The default architecture of the internet is about connecting people!" We agree! @OpenNetAfrica #FIFAfrica16

— CIPESA (@cipesaug) September 28, 2016

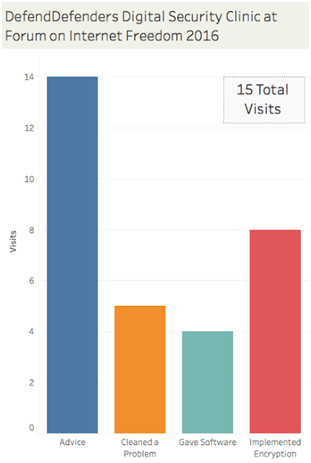

For the first time, FIFAfrica hosted digital security clinics for participants.The digital security clinics, which were offered by DefendDefenders, responded to digital security questions, offered advice regarding digital safety, provided basic digital safety software and removed malware and unwanted software from affected devices. It created awareness of the security gaps that everyday devices have, with participants whovisited the clinic having their devices secured.

For the first time, FIFAfrica hosted digital security clinics for participants.The digital security clinics, which were offered by DefendDefenders, responded to digital security questions, offered advice regarding digital safety, provided basic digital safety software and removed malware and unwanted software from affected devices. It created awareness of the security gaps that everyday devices have, with participants whovisited the clinic having their devices secured.At #FIFAfrica16? Stop by and get your digital security questions answered at the @EHAHRDP clinic help desk @cipesaug pic.twitter.com/SxozeDJSaT

— Neil Blazevic (@neilblazevic) September 28, 2016

The clinic served 15 participants and addressed various digital security concerns including email hacking, how to recover stolen laptops, enabling basic computer security, full disk encryption and how to encrypt communication.

“For one visitor from Ethiopia, we gave a crash course in digital safety, shared knowledge about passwords and installed a password manager for him. We also installed a malware scanner which neutralised 60 potentially unwanted programs from his computer. We also installed Betternet, a virtual private network that circumvents internet surveillance and censorship. In addition, we uninstalled a couple of programs that looked like Trojan viruses. “

DefendDefenders Team

A breakdown of the types of assistance provided to the 15 clinic visitors represented in the chart

Look out for the #DigitalSecurity Clinic by @EHAHRDP - Get digitally secure at #FIFAfrica16 - #InternetFreedom pic.twitter.com/Bu19pGYJoT

— CIPESA (@cipesaug) September 28, 2016

We do a lot of 'digital hygiene', but not enough practice of digital safety & security. #FIFAfrica16

— Koketso Moeti (@Kmoeti) September 28, 2016

Panelists: Ebele Okobi - Facebook | Ife Osaga-Ondondo - Google | Vincent Bagiire - ICT Policy Analyst | Anriette Esterhuysen - Association for Progressive Communications (APC) | Tefo Mohapi - iAfrikan (Moderator)

Vast amounts of user information is generated, stored and shared online, a large amount of which is eventually owned and stored by private entities. Conversely, the amount and type of data governments could access about an individual shifted into the online arena and thus, out of their immediate jurisdiction in many instances.

EbeleOkobi and Ife Osaga-Ondondonoted that Facebook and Google often receive user information and take down requests from both state and non state actors, which are handled on a case-by-case basis. Towards promoting transparency and accountability to their users, both companies publish period transparency reports (See the Facebook Global Government Requests Report and Googletransparency reports).

While fellow panelistsAnrietteEstherhuysen and Vincent Bagiire commended what the intermediaries were doing with regard to transparency, they noted that the transparency reports do not give enough information on the requests and handling procedure. Both intermediary representatives stressed that user information and takedown requests are handled within the confines of law and follow due process. However, they also called for government to be transparent when they shut down online communications. Esterhuysen called for additional transparency by intermediaries particularly when it comes to personal data take downs.

While fellow panelistsAnrietteEstherhuysen and Vincent Bagiire commended what the intermediaries were doing with regard to transparency, they noted that the transparency reports do not give enough information on the requests and handling procedure. Both intermediary representatives stressed that user information and takedown requests are handled within the confines of law and follow due process. However, they also called for government to be transparent when they shut down online communications. Esterhuysen called for additional transparency by intermediaries particularly when it comes to personal data take downs.The “grey areas” in user terms and conditions were also discussed with panelists and audiences alike questioning whose responsibility it was to educate users. According to various submissions, this concern wascompounded by users’need to simply reach an end product without adequately understanding the extent to which their data will be processed and accessed and the related risks to privacy.

The discussion explored whether companies are “hiding behind terms of service” due to their complex and difficult language that results in the end user carrying the risk. Panelists called for simplifications of the terms of service to make them more accessible.

It was also pointed out that it is unknown which third parties have access to Google and Facebook user data. In particular, the relationship between Whatsapp and Facebook was brought to the fore with concerns about the extent of information shared between the twoentities. Users need to know what their rights are and providers need to make clearer their terms and conditions in a manner that is easily understood by users.The Facebook and Google representatives agreed that this could be improved upon and welcomed suggestions on how this could be pursued.

The location of infomediaries outside the continent was also questioned on a legal and tax basis as well as local content.

Participants were encouraged to exercise their right to information and to query intermediaries where they see gaps or concerns as these entities have become fundamental to internet users globally.

Here in Kampala at #FIFAfrica16 we are doing very vigorously! https://t.co/CvwuaJQDmN

— anriette (@anriette) September 28, 2016

A public dialogue was held at the Forum by the Africa Freedom of Information Center (AFIC) in partnership with the CIPESA and Uganda’s Office of the Prime Minister under the theme Promotion ofUniversal Access to information through all platforms as an essential means of achieving 2030 development agenda and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The relationship between access to information and SDGs formed the basis of discussions which aimed to create awareness of citizens’ access to information, strengthen engagement between citizens and anti-corruption agencies, and deepen and broaden the knowledge base on access to information and anti-corruption.Discussions were supplemented by a video on access to information which stressed the role that the right to information played in development, transparency, anti-corruption as well as in promoting civic participation.

A baseline study on access to Information laws and anti-corruption which was conducted in Uganda, Kenya and Malawi was also shared. The study drew inputs from civil society organisations, journalists, public bodies, and anti-corruption institutions.Henry Maina of Article 19 said information remains out of reach for manymarginalized communities including persons with disabilities and women. He added that inadequate government information management systems continue to fuel corruption,and undermine proactive disclosure by officials. This point was reiterated by AFIC’s Gilbert Sendugwa who added that many public contracts overshoot their planned budgets often due to absence of the combination of “disclosure” and “public participation”.

While work on attaining the SDGs takes shape on the continent, not all African countries have enacted an Access to Information law to support the relisation of these goals. However, it was noted that instruments like the Africa Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption (2003) still play a role in supporting information release and as of 2016, 37 African states had ratified this Treaty.

The relationship between open data, service delivery and the right to access information was also discussed with particular focus placed on open contrating data (OCD) standards. Reference was made to the Uganda open contracting and monitoring website Budeshi,which links budgets and procurement data to various public services and projects. Ultimately, it aims to use open data and the civic right to information to determine whether citizens are getting adequate public service at value for money, in a timely manner and free of the abuse of state funds.

Upon conclusion of the dialogue, participants were encouraged to exercise their right to information. Further, officials in a position to release information were encouraged to proactively disclose information and respond to citizen’s requests as they are mandated to do so by the law.

Panelists: Neil Blazevic - DefendDefenders | Kelly Daniel Mukwano - iFreedom Uganda | Natasha Msoza - Digital Society of Zimbabwe (Moderator) | Mary Kiio - Digital Security Training Consultant | Lindsay Beck - Open Technology Fund (OTF)

The panel which comprised of digital security trainers and online rights activists noted the growing need for digital security skills. Concerns of communications being snooped upon have given rise to new tools as internet users seek to insulate themselves against existing, potential and assumed surveillance.

Session 3b: How can #tech be used to defend the defenders? Can we connect #InternetPolicy & #Tech | #FIFAfrica16 pic.twitter.com/p6I1fh74Ia

— CIPESA (@cipesaug) September 28, 2016

However, a call for continuous training was made, as the current approach which is primarily a one off-training model employed by most initiatives was not sustainable given the likelihood for beneficiaries to regress to default (unsecure) means of online communication after the training. . The challenge of limited resources for continuous training was stressed by Mary Kiio, who added that dedicate trainings should target more women, as an increasingly at-risk group given the growing trend in online violence against women.

As always when talking digital security, @Info_Activism's 'Security in a Box' came up. Check it here https://t.co/nOvQgzJhVx #FIFAfrica16

— Koketso Moeti (@Kmoeti) September 28, 2016

Discussion turned to how digital security trainers can follow-up on their trainings. Lindsay Beck noted that OTF’s fellowship programme seeks to ensure a long-term relationship where fellows are trained over a period of time and in turn transfer those skills to the grassroots.

Nonetheless, digital security still remains a novelty for many African organisations including human rights defenders. Indeed, Neil Blazevic stressed that strategically selected individuals such as journalists and bloggers were easier to followup compared to organisations that have bureaucratic structures. Value addition to digital security training was cited as vital for skills retention.

Kelly Mukwano noted that some tools mostly developed in Europe and America are not always compatible with devices and bandwidth available in local contexts. He applauded OTF for working with developers/techies to incorporate user-centred design to accommodate the local context. The developers, Kelly added, should tackle the language barrier by localising content and a wider variety of tools.

Discussion with the audience revealed a need for the introduction of digital awareness from an early age - while still at school - in order for it to become part of social behavior. However, it was noted that there was a tension between “security consciousness and outright paranoia” on the use of online communication tools.

Resources recommended for digital security information included ssd.eff.org, securityinabox.org and safeonline.ng, while OTF open source digital safety material can be accessed from Github among other open source projects and tools hosted on the same platform.

Panelists: Ephraim Percy Kenyanito - Access Now | Yosr Jouini - DSS216 Tunisia | Arthur Gwagwa - Strathmore University (Moderator) | Arsene Tungali - Rudi International (DR Congo) | Wisdom Donko - National Information Technology Agency (NITA) Ghana

In the first six months of 2016, there were at least 20 internet shutdowns worldwide whereas in2015 there were 15 internet shutdowns reported. The growing trend has been justified on various grounds including to allegedly guard against cheating in national exams, and to protect public order during elections and protests.The length of internet shutdowns also vary by country.Panelists noted that shutdowns were often initiatedby governments on the basis of panic, a need to control the flow and type of information shared, and fear of mass mobilisation.

While concern was expressed over the government monopoly over communications in countries such as Ethiopia facilitating shutdowns, it was noted that even in countries with a liberal communications sector, internet shutdowns still occur as Internet Service Providers always obey government instructions to shutdown communications.

“It can be very scary…suddenly you cannot use your emails, social media accounts and sometimes even make phone calls. One is taken back a century when the internet was not there and there was no form of communication.”

Arsene Tungali, Congo

Audience members queried the role of intermediaries such as Facebook and Twitter during internet shutdown sbut it was clarified that governments orders ISPs to block access to particular sites. Ephraim Kenyanito cited two instances, in Turkey and Brazil, where a shutdown was implemented following a court order.

Ultimately during this session, the consensus was that shutdowns, under any circumstances cannot be justified, as such governments should not shutdown communications but rather put in place mechanisms to address specific concerns.

shutting down the internet is not justifiable in any circumstance #FIFAfrica16 @cipesaug @APC_News

— Olive Tsafack (@OliveTsafack) September 28, 2016

In conclusion, it was noted that shutdowns do not just infringe on freedom on expression and right to information, they also violate various social and economic rights.The session called for more engagement between governments, civil society, citizens and other stakeholders specifically on the issues and events leading up to internet shutdowns and how to mitigate related challenges.

Panelists: Edet Ojo - Media Rights Agenda (Nigeria) | Tusi Fokane - Freedom of Expression Institute (FXI) (Moderator) | Henry Maina - Article 19 (Kenya) | Maiylin Fidler - Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard Law School | BoyeAdeboke - Paradigm Initiative Nigeria (PIN)

It was noted that a good internet framework supports an open internet, increased access, and promotes the rights and equality of all individuals in the entire online ecosystem. Further, it recognises the distinction between cyber-crime and cyber security by defining crimes of access and privacy breach while upholding confidentially, data integrity and data protection. It also doesn’t grant excessive powers to the state or public bodies.

"In some cases digital security awareness is needed as much as trainings " #FIFAfrica16

— Yosr Jouini (@YOoJOo_) September 28, 2016

Panelists noted that various laws are used to curtail online expression and to promote self-censorship which goes against the spirit of a free and open internet. These laws are often used to crack down on dissenting voices. The Nigerian Digital Rights and Freedom Bill was referred to as a model for internet rights in African countries.

Question: Can Access to Internet be regulated? Can Access and privacy go hand in hand? #AccessToInfoDay #FIFAfrica16 pic.twitter.com/LaRVADkS9p

— AfricaInternetRights (@AfricaNetRights) September 28, 2016

Discussions went on to query whether a harmonised internet freedom framework in Africa is possible. Panelists noted that while this is desirable, various barriers still exist. These include the lack of political will and government engagement on issues of internet governance. The absence of political cohesion is also a threat such as to date, no country has ratified the African convention on cyber security and personal Data protection. To address these barriers, panelists called for strategic engagement to challenge cyber bills particularly during legislative processes. Further, the active inclusion of more stakeholders in policy formulation was called for.

The important role the internet plays in the lives of ordinary citizens both directly and indirectly makes it imperative to develop suitable frameworks that safeguard and accommodate the diverse needs of citizens. As such, it is important for citizens to be part of the policy making process.

Citizens remain mostly unaware of the laws and policies that apply to their online activity.Poor efforts by government to consult stakeholders contribute to the low levels of civic participation in policy making. Further, issues of language, the perceived exclusivity of legal processes also serve to alienate citizens who would otherwise participate. Existing social and economic inequalities also contribute to the alienation of citizens from active participation in policy/law developments.

Panelists urged civil society to do more work to create awareness of frameworks applicable to internet use.

Digital inequality is made of this. Replicating th same age-old inequalities! #FIFAfrica16 https://t.co/9MEqoiXRUT

— Nanjira (@NiNanjira) September 28, 2016

Panelists: Angela Kilusungu - Culture &Development East Africa (CDEA) | David Kaiza - Ugandan Writer | Mildred Achoch - ROFFEKE Rock ‘n’ Roll Film Festival Kenya | Violet Nantume - Artist and Curator | Ahmed Ahmed - Egyptian Multimedia Journalist

"Art is not just a hobby. It's activism, it's debate, it's conversation. It's a whole lot more." ~ Violet Nantume #FIFAfrica16

— Carol Beyanga (@Akeda3) September 28, 2016

Amazing suggestions on what #FIFAfrica16 should explore - See this contribution by @Mwalimu_Anyole from #Uganda pic.twitter.com/szIN7TxpNT

— CIPESA (@cipesaug) September 28, 2016

The potential of online platforms as a market avenue for products that are not locally popular or face social restrictions was acknowledged, including the lower costs associated with the use of the internet while maintaining the potential to reach a wide audience.

The value addition of free online tools which support creative content (such as editing, visualization and post-production) were also highlighted while the growing popularity of platforms like YouTube as a tool to share content and to generate income was also noted. However, panelists agreed that many artists have yet to reach the true potential in using such tools.

Many things that sell offline also sell online. ~ Mildred Achoch #FIFAfrica16

— Joel Jemba™ (@joeljjemba) September 28, 2016

How do we distinguish b/n sexuality issues from pornography - Voilet #FIFAfrica16

— Kofi Yeboah (@kofiemeritus) September 28, 2016

The creation of social commentary through art by the creative community particularly on what are considered sensitive topics including issues of sexuality and politics is not always welcomed. Panelist Violet Nantume recounted how Facebook took down her post dealing with women and sexuality in Uganda. This came as a result of complaints by members of the public that were uncomfortable with the topic.“It is difficult to spark debate and talk about difficult issues that people are uncomfortable with such as sex education and sexuality without being shut down,” She noted.Egyptian multimedia journalist Ahmed Ahmed recounted his experience of being blocked from posting opinions on sexuality on a website. He then resorted to expressing his views through nude photography but cannot post this material on his Facebook page for fear that it could be closed down.

Question: Is technology enabling the dilution of legitimate creative expression? #FIFAfrica16

— Joel Jemba™ (@joeljjemba) September 28, 2016

In Tanzania, it was reported that a very active film censorship board (Tanzania Film Censorship Board {TFCB}) vets films at script and at film level. In Uganda, the Uganda Communications Commission is mandated to review content before it is aired but this is not done regularly. Nonetheless, self-censorship is practiced in the artistic community.

The largest theatre in Uganda belongs to the state, #FIFAfrica16 #creativity #Censorship

— #Documentary (@NhillFilms) September 28, 2016

As a result, panelists noted that self-censorship is generally caused by pressure from audience with whom they want to engage.The session considered that limited Internet accessibility in many African countries, creates challenges in bridging the gap between offline and online expression and content. While social media platforms like Facebook and Whatsapp are popular, aspects of these platforms are by design closed, thus limiting the reach of content in some instances.

There was consensus that artistes should popularise their work equally offline and online alongside building awareness on the role that artistic expression plays in society and indeed in social justice. It was stressed that bridging the gap between social commentary through art and technology will ultimately require well planned strategy that goes beyond simply uploading material.

The panel on Creatives and their use of the Internet has been awesome. #FIFAfrica16 pic.twitter.com/0hGaPfAmk7

— Talkative Rocker (@beewol) September 28, 2016

Panelists: Daniel Kalinaki - Nation Media Group | Lydia Namubiru - African Centre for Media Excellence (ACME) | Thomasi Pa Louis - International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) Africa | Koliwe Majama - MISA Zimbabwe (Moderator) | Eric Chinje - Africa Media Initiative

Panel on "Clickbait Journalism: Experiences in African Media" at #FIFAfrica16 pic.twitter.com/yfsac2JTGZ

— iAfrikan (@iafrikan) September 28, 2016

Panel on Journalism & click bait in African media.@namlyd @Kalinaki #FIFAfrica16 pic.twitter.com/m1GxTsipKA

— Rosebell Kagumire (@RosebellK) September 28, 2016

The internet has allowed for a wider diversity of news stories to be collected since many citizens have become content originators/contributors. The popularity of social media has further “democratised” the online media arena as it has improved access to news. However, while various advancements in technology have eased the news creation and dissemination process, such as enabling quicker fact checking and reduced overhead costs, the ethics around the practice of journalism have suffered.

Social media has actually made the work of traditional media more easy and to some extent reduced cost says Thomasi from IFJ #FIFAfrica16

— CIPESA (@cipesaug) September 28, 2016

It was argued that despite the amount of content continuously generated and made available online, a common ground needs to be found that recognises traditional media ethics but also integrates new media models and audience needs. This is in contrast to past media models where content was determined by editors. Currently, the openness of the internet has enabled consumers to determine content that they are most interested in thus shifting the balance of power and as a result the media is struggling to cope.

Look out for the #DigitalSecurity Clinic by @EHAHRDP - Get digitally secure at #FIFAfrica16 - #InternetFreedom pic.twitter.com/Bu19pGYJoT

— CIPESA (@cipesaug) September 28, 2016

@Kalinaki: The newspaper's biggest competitor today is the telephone company, Facebook, and Google, not another newspaper. #FIFAfrica16

— Peter Mwesige (@pmwesige) September 28, 2016

Further, panelists noted that competition is coming from more angles than ever before – it no longer in the form of another newspaper/media house. The popularity of various apps as information sources is also forcing traditional media to rethink their content and business models – particularly when it comes to advertising. Readers are using apps to reach content and are not necessarily turning to specific websites for information, thus, traditional media houses’ websites are not always a primary source of information as they once were, weakening their potential for higher advertising spend. Consequently, some have resorted to clickbait to maintain high traffic to their websites and to attract advertisers largely driven by website traffic.

Panelists agreed that clickbaiting is merely part of a bigger challenge that media houses are facing which is the absence of a depth of information on the traits of the digital news consumer whose character is defined by short attention spans, reading and listening for a shorter time, and thus, is easily baited by catchy images and headlines. They stressed that it is important to figure out the long term character traits of such consumers in order for media houses to be in a position to adequately meet the needs.

The hunger for good content is there, we don't need to recreate that. but how do we produce good content? asks @Eric1chinje #FIFAfrica16

— CIPESA (@cipesaug) September 28, 2016

Although mainstream media houses have embraced various online tools, they have not necessarily packaged their content to meet emerging audiences - many newspapers simply lift editorial content and upload it on their websites whereas online readers are a little more sophisticated and are seeking interaction on the issues.

#Technology has revolutionalized the way we get #news Everyone vies for our time. #MediaHouses must adopt, So much has changed #FIFAfrica16 https://t.co/Cw29OM2r2S

— Nansinguza Jacob (@NansinguzaJ) September 28, 2016

It was recommended that an intersection between ethical content and sustainable business models is required which also recognises that multiple models may be needed to suit different audiences – this includes for instance paid subscription for content. However, there was some skepticism on the readiness of African audiences to pay for online content, a situation compounded by the fact that there are not enough readership numbers to make business sense particularly if the price of content is high.

Further, media content of African origin still faces competitive pressure from international media agencies. Given the negative narrative that Africa still receives from the global media, the internet has provided an avenue to change this. While this counter narrative may provide the possibility to address these stereotypes, it is also threatened by trends in clickbaiting which tap into these very stereotypes and thus perpetuate negative portrayal of the continent and its people.

Panelists agreed that one of the ways to counter the narrative would be to improve ethics including on addressing the publication of false stories. It was noted that in online publishing, whether the error was intended or not, one gets punished. “Should the media compete on getting the story first or getting the story right?” This question remains a paradox as it is not only present only on online media but also in traditional media.

Find your value lane. Are you going to place your competitive advantage on breaking the story first or getting the story right?#FIFAfrica16

— Martha ♡ (@ChilongoshiM) September 28, 2016

The session also raised questions for further discussion including whether it is still meaningful for media to have the definitions of traditional and new media? Is this part of the problem, are old practices being held onto? Another question raised was whether the media should worry about the messenger (message form) or rather focus on the message?

"Journalisme et expériences dans les media africains":conclusions de "certains" panélistes @Eric1chinje,@Kalinaki,@cipesaug,#FIFAfrica16 pic.twitter.com/cmyKEOiq8S

— APCNouvelles (@APCNouvelles) September 28, 2016

Panelists: Bernard Sabiti - Development Research and Training (DRT) | Henry Muguzi - Alliance for Campaign Finance Monitoring (ACFIM) | Richard Ngamita - Outbox | Stanley Achonu - BudgIT | EmilarVushe, APC (Moderator)

Despite the vast amounts of public data held by the state, access to information laws continue to be poorly implemented or non-existent in many African countries and this limits access to or use of such data. In instances where public data is made available, it is sometimes in formats like PDF which cannot be easily manipulated or are incomplete. Panelists called for the proactive release of data in reusable formats (excel, csv) by governments but also criticised civil society organisations for not being open with their own data.

Panelists noted poor government support for open data which is aggravated by poor implementation of access to information laws. Combined, these continue to limit the opportunities for transparency and accountability. Bernard Sabiti noted that many governments still get unsettled when terms like ‘open data’ and ‘citizen generated data’ are used. Amidst the various challenges faced on the release of data, panelists recognised a number of public offices in their respective countries that are working to change their practices on the release of information. The Bureau of Statistics of Nigeria and the Ministry of Finance in Uganda were mentioned as offices that have been a reliable sources of data in a timely manner and in usable formats.

However, a bigger concern shared was the limited availability of the skills required to translate raw data into easily accessible information. Panelists noted the absence of funds to build this capacity which, is a concern in many African countries. It was also stressed that data provides an avenue for informed decision making and indeed an avenue to support advocacy for human rights in Africa.

A participant raised concern about the safety of whistle-blowers who utilise open data to expose the misuse of funds and human rights violations. Panelists encouraged more citizen-led activism and adoption of digital security tools for data analysts and actors who are utilizing data in human rights monitoring and anti corruption.

The use of data sourced through social media was seen as an area for further exploration due to the immense amounts of data shared by users. However, the ethics on the use of this data was questioned. Stanley Achonu emphasised the attribution of data sources used in social media mining to help address ethical concerns but also support the authenticity and verification of reports. While social media mining is gaining popularity, much of the data required is locked away by the social media intermediaries - with high access costs to access it. Richard Ngamita pointed out that social media mining is another area where skills are limited on the continent.

There is a massive skills gap to turn data into insight. @outboxhub wants promote data literacy ~ @ngamita #FIFAfrica16

— Mwesigwa Daniel (@valanchee) September 28, 2016

Access to data in national archives was also raised. However, it was also revealed that a lot of work remains to be done in many countries to digitize and archive historical data.

Panelists: Nashilongo Gervasius - Namibia Broadcasting Corporation (NBC) (Moderator) | Zawadi Nyong’o - Digital Media Strategist | Martha Chilongoshi - Revolt Media Africa | Akua Gyekye - Facebook | Ray Mwareya - Freelance Journalist

Millions of women and girls are subjected to deliberate violence on a daily basis and increasingly, this violence is manifesting itself in various forms online. Panelists noted that violence online depends on ‘who you are, where you are, and how you are experiencing it’. AkuaGyekueadded that online violence against women is not a single issue but is one that is nuanced and which ought to be understood within its various characteristics. As such the segmentation of internet users which recognises their diversity and contexts is paramount in addressing cyber violence against women (VAW).

Panelists noted that documentation of cyber VAW remains grossly lacking as there are few research reports on the topic – and suggested that future reports take into account the aforementioned segmentation. To this end, Facebook is gathering cases reported on its platform in order to develop response mechanisms which can also encourage more incidents to be reported. Since victims of cyberVAW become less vocal, or completely remove themselves from the online arena, panelists called for women to continue to “occupy digital platforms”and to use these very tools for solidarity and to address cyber VAW.

“Cyber violence is an extension of the inequalities existing offline. Offline, women’s abilities and capabilities are often undermined because we are women."

NashilongoGervasius

The transfer of violence and marginalisation of women online is mostly a reflection of existing offline behaviours and perceptions. Panelists pointed out long-held cultural practices which still influence the use of the internet by women and indeeddominate the narrative online. These included the control of decision making and financial choices through to the ownership of physical and digital technologies.

Below are some highlights from the session:

- VAW online is fuelled by perpetuation of misinformed stereotypes: The positions taken in online attacks sometimes become the dominant sentiment and thus, the norm. This has been seen in attacks on women perceived as feminists – where feminism and/or association with it is perceived as negative.

- Mainstream media is part of the problem: The manner in which mainstream media treats and reports on women serves to perpetuate stereotypes and gender generalisations - in many instances degrading and objectifying women for purposes of increased sales (particularly in tabloid media).

- Clickbait in online content based on women’s nudity: Related to the above point is the use of sexualised text and images text to attract users to a page and thus monetisingwomens bodies.

- Prominent women:Women in politics and those in positions of power as well as and women associated with taboo or controversial topics are often easy targets of cyber VAW and bullying due to their level of exposure in the public domain. Attacks are often based on personal reputation, traditional gender roles and culturally assigned tasks which often exclude women from being vocal or from holding positions of leadership. Often, these attacks have no basis and are un-instigated.

- Entitlement: In similarity to cases of offline violence against women, in the online sphere some men maintain a sense of entitlement. This manifests itself in the use of women’s nude pictures as a means to attract attention or leverage (e.g. revenge porn for a failed advance or relationship).

Suggestions on how to change the narrative were wide-ranging and included the development of tools that recognise and respond to the diversity of women’s needs online. Below are suggestion from the discussion:

- Simple tactics such as not sharing content that is damaging to anyone’s reputation.

- More media and online content influencers Intentionally recognising women in politics and key positions who face character assassination and trolling

- The development of partnerships for resource and information sharing are key to enabling more active women online and to addressing cyber VAW.

- The media should more actively exposecyber VAW and also address the ethics of profit versus virtue. This includes changing mindsets of editors in covering critical women’s issues (Reference was made to the Uganda television station NTV, which fired a female presenter who had fallen victim to revenge porn). The media should also raise awareness about how cyber polices are gender discriminative e.g. Uganda’s Anti-Pornography Act.

- The participation of men in fighting cyber VAW is also key as it serves to raise awareness for men to change their attitude and ignorance.

- More women need to be digitally secure, which can be supported by making more useful information available. This can also be supported by awareness and development of personal social media strategies.

- Online campaigns should be supported by offline campaigns to drive social change and to tap into collective action to address VAW both online and offline.

- The development and popularisationof manuals on how to deal with cyberVAW is needed – these should be easily accessible and in diverse languages.

- Naming and shaming lists of perpetuators of cyberVAW can be used as a means to deter other perpetrators.

- Service providers should tailor user experiences and responses to the various needs of women online ie recognise that women are not a homogenous group online.

https://twitter.com/ChilongoshiM/status/78112866911270092

Peter Magellah - Uganda | Natasha Msonza - Zimbabwe | John Jean Paul Nkurunziza Kenya ICT Action Network MaxenceMelo - Tanzania | Hellen Mwale Zambia

One of the highlights at FIFAfricais the launch of the State of Internet Freedom in Africa report. The report provides a summary of in-depth research findings on internet freedom in select African countries. In 2016, the countries featured were Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Somalia, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe. The report, themed “Strategies African governments use to stifle citizens’ digital rights”saw researchers use various research methods including desk research, policy analysis, key informant interviews, and tests on websites.

Research in Tanzania was conducted shortly after the inauguration of John Magufuli as president and “who cut a no-nonsense posture” leading to respondents being afraid of antagonising the new government and calling for anonymity. Similar sentiment was present in Burundi which over the course of the year (2015/2016) was caught in political turmoil due to the president’s term extension. The researcher reported that conducting research in the country was a lot harder compared to previous years owing to the tensions.

In Zimbabwe, informant interviews were relatively easy to conduct as long as respondents were assured of anonymity. In Uganda, in the wake of two internet shutdowns in February and May 2016, it was reported that “an aura of secrecy has set in” particularly when trying to source information on digital rights. Further, the participation of law enforcement or regulatory officials was met with hesitation as many were unwilling to contribute or be quoted even after assurances of anonymity.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, looming elections also influenced the extent to which key informants were willing to contribute to the research as they did not want to be seen as “raising complaints”. Although some opposition politicians and human rights activist availed themselves for the research, many were reluctant to be quoted.

The Kenyan researcher had a much easier experience due to the larger amount of information readily available in the public domain in comparison to the other countries the research was conducted in. It was reported that government officials were not too secretive but delayed to respond. In Zambia, obtaining information from government entities was a protracted process which was partly attributed to the absence of an access to information law,and general reluctance of public officials to share information.

A common theme present across the countries was the omnipresent fear of surveillance which impacts the extent to which potential key-informants participate in such research.

The session also addressed strategies for protecting the sources that provide information captured in the report. It was suggested that building the capacity for evidence-based research would be a key means of protecting sources. Some of this capacity is available through online apps that use open source technology to gather information. The other option is using probes through which local researchers can also be protected as their identity remains anonymous. However, concerns were raised about these toolsasthey cannot be used to adequately support the capture of personal/human interest stories which add depth to the report. It is the sources of these stories that need protection. Following the discussion, several suggestions were made on the research process and report including:

- Work more closely with CSOs and national human rights organisations to enhance advocacy based on the insights gathered in the research.

- Strive to capture demographics of usage and ownership of technology for different population segments as data to inform various advocacy campaigns.

- Ensure more inclusivity of minority groups in terms of race, religion and sexual identity among research respondents.

- Establish mechanisms that capture data of both on-grid and off-grid surveillance systems.

- Develop strategies for engaging with policy makers using the report findings.

- Repackage findings to make them more easily accessible for dissemination and consumption by different audiences.

- Translate the reports into more languages such as French for the benefit of non Anglophonecountries that are also featured in the report.

Reports in the State of Internet Freedom in Africa Series

|

|

|

| State of Internet Freedom in East Africa 2014 | State of Internet Freedom in East Africa 2015 | State of Internet Freedom in Africa 2016 |

Panelists: Ebele Okobi - Facebook | Anthony Chigaazira - Communications Regulators Association of Southern Africa (CRASA) | Wisdom Donko - National Information Technology Agency (NITA) Ghana | James Wire Lunghabo - ICT4D & SME Business Consultant (Moderator)

The session kicked off with an exploration of what is affected during an internet shutdown. It was agreed that public services, education systems as well as CSOs and even the government are all affected in the event of an internet or selected communications shutdown. Ultimately, most sectors are affected by blocks in communication which is the backbone of social, economic and political interaction at multiple levels.

It was noted that businesses, particularly small businesses, are hardest hit due to lower turnover levels. A break in business operations could more easily result in business closure for such entities than it would for larger ones. Alternatively, it was noted that it would be harder for such businesses to bounce back due to limited safety nets. This is ever more critical in Africa where data and information on the informal sector which dominates the majority of African economies is not systematically captured in the official statistics.

@wirejames : Who gets hardest hit when there is internet shutdown? @Kmoeti @roffeke @BeckLindsay @joeljjemba @beewol #KeepItOn #FIFAfrica16

— Marvin (@MarvinAlinaitwe) September 29, 2016

Panelists agreed that research is still needed to understand the true impact of an internet shutdown as it is important to quantify online enabled cash flow and exchange between individuals and businesses formally and informally as well as at local and international levels.Without clear basis of calculation, the loss per day during the shutdowns in Uganda was estimated at 25 million dollars including losses made over mobile moneyand other services.

The primary players in shut downs were pointed out as governments and telecom companies. While governments may issue the internet shutdown instruction, it is telecoms companies who primarily lose trust among their clients for effecting the shutdown. “Are telecoms biting the hand that feeds them?” was an undercurrent of the discussion with consensus that there has to be the development of relationships between multiple stakeholders that can be used to mitigate future internet shutdowns.

Since the Forum, the Brookings Institute report on Internet shutdowns was released.

National security and public order have often been cited as reasons for internet shutdowns, however, with little actual justification. James Wire Lunghabo pointed out that often fears are based on leaders being averse to citizens engaging in certain conversations that they cannot moderate or control.As such, EbeleOkobi called for the need to quantify the security threats as currently, blanket shutdowns have set a dangerous precedent.

In Egypt, the 5Days Internet Shutdown led to a loss of US$ 110 Millions. #FIFAfrica16

— Samwise Gamgee (@Sambannz) September 29, 2016

Further it was suggested that government officials need to be sensitised about internet governance issues due to actions taken out of ignorance including how to use technology to engage during times of crisis. Further, it was stressed that there should be more discoursebetween governments and different stakeholders such as the private sector, media and civil society on how to address perceived national security threats. Additionally, meaningful partnerships and collaborations should be developed between governments and civil society on internet governance issues.

DRC Internet shutdown experience: "Imagine not being able to email, tweet, FB, Whatsapp, even make calls!" What would you do? #FIFAfrica16

— IG: @ZawadiNyongo (@ZawadiNyongo) September 28, 2016

At a technical level, the development of systems to thwart shutdowns was proposed with calls for multi-national technology companies such as Facebook and Google to support the development of such robust systems. The proposal was however questioned on grounds that it could be illegal for these companies to develop systems that circumvent national legislation since shut downs are almost always ordered by governments.

The Internet Shutdown In Ethiopia Costs The Country Approximately $500,000 A Day In Lost GDP https://t.co/hZ7IoQYAbZ #FIFAfrica16

— Arsene Tungali (@arsenebaguma) November 11, 2016

Panelists: Gbenga Sesan - PIN | Ife Osaga Ondondo - Google | Alexandrine Pirlot De Corbion - Privacy International (PI) (Moderator) | Jimmy Haguma - Uganda Police Force | Michael Lishebo - Cyber Security Practitioner, Zambia

In an age where digital data is constantly being generated, cyber–security has become synonymous with technology use. The borderlessness of information has added to the challenge of cyber-security particularly where information of large proportion is held by states and global private entities.

While various countries have developed country specific laws and standards such as the Zambia Cyber Law 2010, Uganda’s Computer Misuse Act of 2011 and the Electronic Signatures Act 2011, and in some instances coupled these efforts with cyber-forensic laboratoriesto address online crime, many gaps still remain. There was debate on whether “we must give up some privacy over freedom” with Zambiancyber-security expert MichaelIlishebo arguing that in most cases, national security will override freedom.

Ife Osaga-Ondono however noted that, as Google, due to the evolving nature of technology, an approach which favours appropriate measure should always be sought. Conversely this should be the approach shared across boundaries on cyber-security. Currently,partnershipssuch as the Northern CorridorIntegration Project which will link land locked countries to the coast are avenues that government are using to create streamlined approached to cyber security.

Bureaucracyat regional and international levels often hampers cyber crimeinvestigationsparticularly in cases where expeditiousness is paramount. However, regional initiatives which are seeing law enforcement agencies share information in real time are helping address such concerns at a regional level.

Panelists noted that despite the presence of policies, implementation still remains lacking. Another specific concern raised was the selective use of some cybercrime laws against members of the opposition and human rights advocates. This was further elaborated upon by a participant from the Media Institute of Southern Africa who spoke of how the Zambia pornography law was used between 2012 and 2014 to intimidate the media.

While data privacy and surveillance were also noted as concerns by participants, law enforcement officialspointed out that the bigger threat comes not from government but from private users who rely on citizen data for advertising and dubious activities which raised the role that infomediaries play in supporting this trend. Osago-Ondonostressed that data privacy is core to Google’s operations and even supported Apple’s stance against a backdoor to user data following a demand by investigators.

Participants called for more action on the online safety of women and children, withpanelists agreeing that it was an area that is being addressed through various mechanisms including through strengthening relationships with law enforcement agencies. There was also a call for increased capacity building among law enforcement authorities in the application of cyber laws including measures for citizens to easily engage with law enforcement on issues of cyber crime.

The conversation on cybersecuirty is an ongoing one due to the ever-changing nature of technology and its use, as such it was noted that transparency and more multi-stakeholder engagements are vital to adequately address emerging concerns. However, it was argued that clear parameters and procedures, accountability and oversight mechanisms are also of utmost importance.