By Martha Chilongoshi |

The Africa I want is one that embraces diversity, promotes freedom of expression, values the right to information and prioritizes the elimination of all forms of discrimination on the basis of gender.

For my ideal Africa to be realized, actions, initiatives and conversations that challenge the status quo and disrupt structural systems which hinder development are very vital and this is what the Forum on Internet Freedom represents for me, an opportunity to meet like-minded people and share ideas as well as experiences on how to advance our societies for the better.

A communication for development professional like me finds great value in the Forum on Internet Freedom gatherings because it presents diverse opportunities for me to learn about the social, economic and political factors affecting internet access and usage in other countries in Africa and how I can apply lessons from there to address and solve prevailing issues in my own country – Zambia.

More importantly, the forum has deepened my knowledge on the role of the internet in the development agenda in that, I have been afforded the opportunity to meet my online community in an offline setting and build a support structure that offers solutions and coping strategies to challenges of internet shutdowns, restrictions on freedom of expression, women’s safety online, privacy and security among other things.

As a gender equality & human rights activist, I particularly enjoyed the session on “Finding equality in an age of discrimination online” with panelists, Emilar Gandhi (Facebook), Daniel Kigonya, (iFreedom Uganda), Caroline Tagny (CAL) and Fungai Machirori (APC). This was an important conversation for me because personally, I have committed to use my skills as a Journalist to create awareness and give prominence to issues that affect women and girls using social media and blogging platforms and in my experience, online spaces have not been spared from the patriarchal structures and attitudes that exist offline

Patriarchy has been defined in the Merriam Webster dictionary as;

– a social organization marked by the supremacy of the father in the clan of the family

– the legal dependence of wives and children, and the reckoning of descent and inheritance in the male line

– control by men of a disproportionately large share of power

With this in mind, it is not surprising that online spaces are being used to perpetuate the very inequalities that exist offline and policing how women and girls express themselves online, how they report violations and how they narrate their experiences. This is why the conversation on “Women’s safety online” by panellists, Francoise Mukuku (Si Jeunesse Savait DR Congo), Irene Kiwia (Tanzania Women of Achievement), Emilar Ghandi (Facebook) and Twasiima Patricia (Chapter Four Uganda) was also very key because it addressed the need to ensure women and girls are protected online and users of the Internet adhere to the set community standards and ideals that deter them from perpetuating abuse and discrimination.

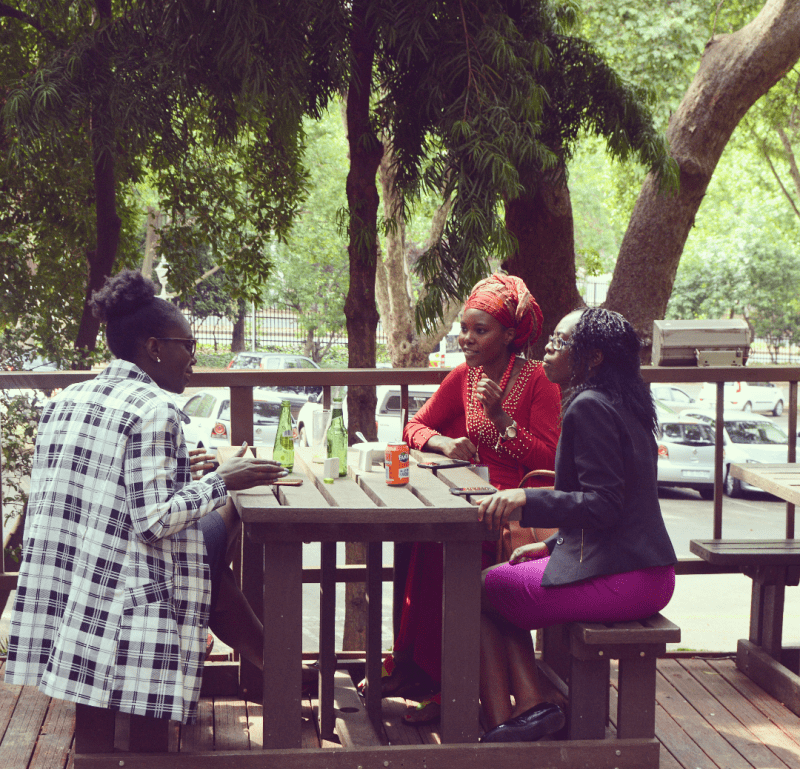

I must add that apart from the panel discussions, I really enjoyed the personal conversations I had during tea and lunch breaks, one of my favourite discussions on the sidelines of the Forum was a conversation about feminism and gender equality with Tricia from Uganda and Tracey from Kenya. As the image below will show, we were so invested in the conversation and it was a brilliant, rich and empowering exchange of young women daring to stand up against structures and environments that perpetuate discrimination using online spaces.

Another key take away from these two sessions was the need to empower women and girls with information about their rights through access to the internet so they can recognise when those rights are being threatened or violated by another person. Often, women and girls are socialised and conditioned to think that they cannot make decisions without the approval of their male relations because from time in memorial, the power lies with men and women are constantly subjected to finding ways of not upsetting this hold on power and in effect remaining silent in the face of violence.

Another key take away from these two sessions was the need to empower women and girls with information about their rights through access to the internet so they can recognise when those rights are being threatened or violated by another person. Often, women and girls are socialised and conditioned to think that they cannot make decisions without the approval of their male relations because from time in memorial, the power lies with men and women are constantly subjected to finding ways of not upsetting this hold on power and in effect remaining silent in the face of violence.

There are many progressive developments that online spaces have provided to ordinary people in terms of dealing with equality, freedom of expression and access to information. More people are now able to voice out on issues that affect them in real time and create a critical mass through social movements that have proved to be a force in challenging the powers that be. This has easily been evidenced by internet shutdowns by governments in Zimbabwe, Cameroon, Togo and Gambia among other countries.

This brings me to another conversation I found most intriguing at the forum themed “Privacy & Freedom of Expression” which was wonderfully moderated by Gbenga Sesan of Paradigm Initiative and featured panellists from state institutions namely James Mutandwa Madya (Ministry of ICT Postal and Courier Services Zimbabwe), Micheal Ilishebo (Zambia Police Service), Marian Shinn (MP, Parliament of South Africa) and Fortune Mgwili-Sibanda (Google).

For the last two years, my line of work has involved working on projects that are centred on democracy, good governance and civic participation especially during electoral processes and this particular conversation was key in understanding how state institutions view the internet and its power to connect people for social change. The conversation between the panellists and audience brought one thing to light, many African governments are threatened by the power that the internet gives to ordinary citizens and as a result, opt to shut it down in order to repress social movements that mobilise people towards an issue.

This can be proved by revisiting how the Zimbabwean government dealt with Evan Mawarire, a pastor whose social media movement dubbed #ThisFlag inspired thousands of Zimbabweans online and offline to demand for better conditions of living from their government. He had to flee his country because his family was no longer safe and when he eventually returned, he was immediately arrested and charged with “attempting to overthrow a constitutionally elected government”.

Another prominent case was that of Cameroon where the Internet was shut down for 3 months in the English speaking region of the country by the government. The shutdown caused hundreds of citizens to mobilise and find alternative means of accessing the internet and creating the hashtag #BringBackOurInternet to let the world know of the discrimination and suppression that was happening in Cameroon. Among the prominent Cameroonian voices that demanded for the restoration of the internet was the Forum’s keynote speaker, Rebecca Enonchong, Founder and CEO of Apps Tech who shared her experience on the impact of the internet shutdown on the rights and freedoms of Cameroonians and to a great extent, its impact on the economy.

If I have to sum up my experience at the forum on internet freedom 2017, I will say that it has given me a fresh and dynamic perspective of the internet, it has broadened my knowledge on the many ways I can use the internet as a tool and an enabler for my human rights activism and encourage civic participation in my community. It has also allowed me to see the economic impact that an internet shutdown can have on a country and for me, this is a great angle from which to advocate for an open, neutral and free internet. I can’t wait for next year’s conversation!

Originally published on the Revolt For Her website