By Apolo Kakaire |

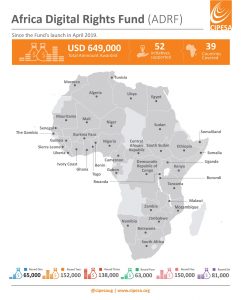

Three years since it was launched and with USD 649,000 disbursed to 52 beneficiaries across 39 African countries, the Africa Digital Rights Fund (ADRF) is powering digital rights policy advocacy and engagement across the continent. According to several beneficiaries, the ADRF is a unique funding initiative that has broken ranks with traditional funders’ structures, and to considerable effect.

The Fund is lauded for adopting a simple application process, allowing for flexibility in implementation, breaking barriers for little-known actors, enabling grantees to build on previous initiatives to ensure greater reach and impact, and supporting local context-specific and responsive projects. This, according to grantees and collaborators who were part of a June 2022 virtual convening on ADRF advocacy experiences which was aimed at promoting learning and best practice.

The ADRF was launched in April 2019 in recognition of the growing role of technology in fostering democracy and promoting equity on the African continent amidst rising arrests of activists, network disruptions in several countries, and restrictive legislation that stifled innovation and human rights online. Moreover, assessments at the time had found that many digital rights interventions were limited in scope, thinly spread across the continent, faced resource limitations, and were often inconsistent in their engagement with digital rights work.

“The situation called for partnerships to bring together different competences to advance digital rights on the continent through seed funding,” said Ashnah Kalemera, the Programme Manager at the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA), the administrators of the ADRF. Those partnerships required provision of flexible and rapid response funding to a range of entities that did not have the ability to attract funding from traditional funders, who have stringent application requirements and lengthy grant application processing times.

With grants ranging between USD 1,000 and USD 20,000, ADRF beneficiaries have undertaken various initiatives focused on technology in society, the public and private sectors. Besides the funding, grantees have also received capacity building in data-driven advocacy and impact communication and media relations. Across the continent, the Fund has helped to strengthen capacity in evidence-based research, collaborative advocacy and impactful policy engagements responsive to regulatory and practice developments that affect the internet freedom landscape.

At the June convening, select initiatives in Kenya, Namibia and Somalia supported by the Fund shared their advocacy experiences. In Somalia, the ADRF-supported work of Digital Shelter has seen a major breakthrough in stakeholder dialogue and engagement on hitherto undiscussed digital rights subjects such as digital inclusion, online civic space, gender-based violence online, digital entrepreneurship, civic participation and data protection and privacy.

“Prior to ADRF’s support, people in the country had no appreciation for digital rights and the consequences of internet shutdowns. The Fund helped us to engage the government to talk about policies and legislation and when the conversation started, the Minister [of Communications and Technology] was very open and he was surprised that there was a local group addressing these issues,” said Ayaan Khalif, Co-founder of Digital Shelter. “The ADRF was an eye opener and helped us partner and link with other organisations and to understand what works in other countries.”

Aayan added that applying for the ADRF funding was an easy process. She said: “We were almost giving up on donor funding after so many rejections. The ADRF process was simple. Some donors complicate things. The [application templates] are in English but sometimes it is as if it is in another language.”

The inroads made by Digital Shelter underscore the importance of collaboration and partnership in advancing digital rights in the region. Zakarie Ismael, the eGovernment Implementation Advisor in Somali’s Ministry of Communications and Technology, stated that the government of Somalia, through the ministry has responded to the appeals of Digital Shelter and other actors by prioritising the technology sector, including through the ICT Policy and Strategy 2019-2024. That government responsiveness has been crucial to the work of digital rights activists. As Ayaan noted, “It makes it easy to make inroads when you have people backing you up in policy advocacy. Our partnership with the government has been very practical in this regard.”.

As legislative and oversight bodies, national parliaments have a key role in advancing digital inclusion and rights-respecting digital policies and practices. Indeed, some grantees, including Mzalendo Trust in Kenya, have dedicated efforts to promoting citizen-parliamentary engagement on digital rights. With the suspension of parliamentary proceedings in Kenya at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, the ADRF supported functionality upgrades to the Dokeza and Bonga Na Mzalendo platforms. The upgrades enabled citizen participation through remote annotation and submission of memoranda on bills including on the controversial Huduma Initiative.

Mzalendo Trust has also worked to promote an inclusive digital economy in Kenya. Like Ayaan, Slyvia Katua, a Programme Officer at Mzalendo Trust, lauded the ADRF for using a simple and straightforward application process. “The application requires you to outline what issues you are targeting, what solutions you offer and what impact you foresee,” she said.

Meanwhile, Josephat Vijanda Tjiho, from the Internet Society (ISOC) Namibia Chapter, appreciated the ADRF grant process for allowing them to build from one project to another. “We organised forums on digital media and elections, then stepped up to privacy and data protection especially around the Covid-19 pandemic and thereafter a campaign against online violence against women and children. Our ideas [which the ADRF supported] were building from one to the other and this made our application process quite smooth,” Tjiho said.

ISOC Namibia conducted research and convened engagements with different stakeholders on data protection, gender-based violence online and access to information. “Based on our engagements, the Namibia Access to Information (ATI) Act was passed in June 2022 and this was partly made possible through support from the ADRF,” stated Tijho. For its campaign against gender-based violence, ISOC Namibia successfully collaborated with prominent personalities including a technologist, musician and pageant as part of the 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence. The campaign fed directly into work on research and workshops on gender-based violence in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region for which ISOC Namibia partnered with CIPESA, Meta, Pollicy, Genderlinks and University of Pretoria Centre for Human Rights.

According to Neema Lugangira, a Member of Parliament (MP) in Tanzania, undertaking digital rights advocacy without involving parliament has created huge gaps in ensuring that policy and legislation around digital rights are rights-respecting and are effectively implemented. She faulted civil society organisations seeking policy reforms for concentrating on other arms of the government and ignoring parliaments yet they play a key role in policy formulation and oversight. She urged ADRF grantees and other digital rights actors to actively engage MPs as part of their programming. “We should prioritise capacity building for MPs because they are ignorant about digital rights,” said Lugangira.

The experiences of ADRF grantees indicate the potential of rapid response and flexible funding in positively shaping the digital rights landscape in Africa through targeted research, advocacy and movement building.