By CIPESA Writer |

Persons with disabilities have unique needs and have for long been disadvantaged, yet, the more some African countries get digitally connected, the deeper the digital divide for this community seems to grow. Indeed, debates about internet governance and the inclusiveness of the information society have not prominently featured the needs of persons with disabilities. This, despite Information and Communications Technology (ICT) having the potential to improve the lives of persons with disabilities.

However, it was a different story in Kenya a month ago, with disability rights featuring prominently at the Kenya Internet Governance (KIGF) and being the focus of a multi-stakeholder workshop held the day before the forum.

“ICT for us is an enabler; for a person with disability, ICT makes the world go round,” remarked Erick Ngondi of the United Disabled Persons of Kenya (UDPK), at the end of a workshop organised by the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) alongside the Kenya Internet Governance Week that is spearheaded by the Kenya ICT Action Network, or KICTANet. “For me this has been one of the first meetings as relates to ICT and disability, so this is an excellent move.”

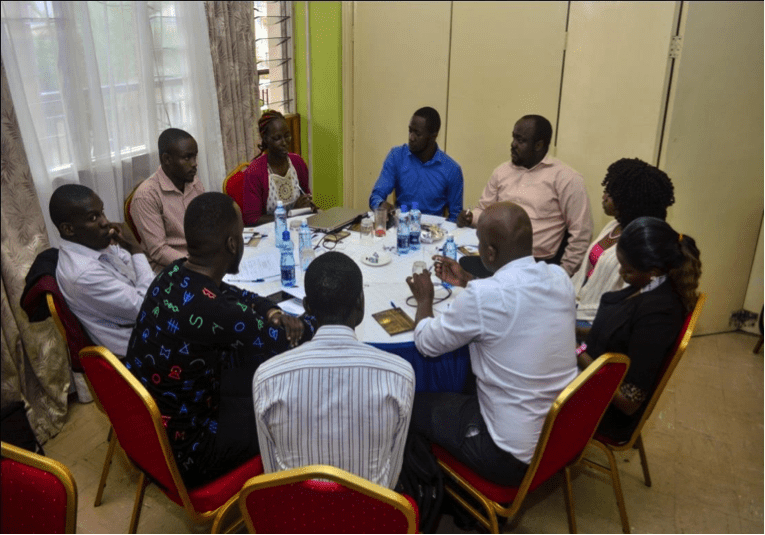

The workshop brought together 28 participants who included representatives of disabled persons’ organisations, government departments, telecom companies, academic institutions, technology companies, civil society organisations, and the media. The workshop explored ICT inclusion obligations for the state and for private companies and discussed what Kenya needs to do so as to improve access and usage of ICT for persons with disabilities. (Watch video with highlights from the meeting.)

“This workshop is one of its kind because it is not only about issues of physical accessibility but also informational and technological accessibility for persons with disabilities. This is a good initiative by CIPESA and I want to applaud them for this. It is a journey that has started and I look forward to us going on with this journey until we achieve our goal of persons with disabilities being included in technology.” George Shimanyula, Cheshire Disability Services Kenya.

In addition, the workshop disseminated a draft tool for monitoring compliance and implementation of ICT and disability rights obligations, including those specified by national laws and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons With Disabilities (CRPD). The aim was to receive feedback on the tool, and to create awareness of how state and non-state actors can assess the compliance of government departments and private entities with digital accessibility obligations.

Kenya’s constitution is strong on disability rights, outlawing discrimination on the grounds of disability in article 27(4); and providing that a person with disability shall be entitled to treatment with respect and dignity, access educational institutions and facilities, have reasonable access to all places, public transport and information, and access materials and devices including for communications (article 54). Moreover, Kenya’s National ICT Policy of 2016 outlines, under article 13, strategies for “an accessible ICT environment in the country in order to enable persons with disabilities to take full advantage of ICTs.”

https://twitter.com/BakeKenya/status/1156905814122217487

However, as was noted by Judy Okite, founder of the Association for Accessibility and Equality, many of the digital accessibility strategies outlined in the 2016 policy remained unfulfilled. While Kenya’s government is making significant steps to move its services online, the platforms are not favorable to those who are visually imparied. “Are we widening the digital divide by moving our services online? Is ICT recognised as an enabler for PWD in Kenya?” wondered Okite.

Unfulfilled: Digital accessibility strategies outlined in the Kenya National ICT Policy 2016

The Government will where appropriate take measures to:

(a) ensure that ICT services and emergency communications made available to the public are provided in alternative accessible formats for persons with disabilities (PWD);

(b) review existing legislation and regulations to promote ICT accessibility for PWDs in consultation with organisations representing PWDs among others;

(c) promote design, production and distribution of accessible ICT at an early stage;

(d) ensure that persons with disabilities can exercise the right to access to information, freedom of expression and opinion;

(e) require both public and private entities that render services to the public to provide information and services in accessible and usable formats for persons with disabilities;

(f) Require content producers for distribution and public consumption in Kenya to produce such content in accessible format such as audio description, audio subtitles, captions and signing for access to persons with disabilities.

(g) ensure that websites of government departments and agencies comply with international web accessibility standards and are accessible for persons with disabilities

(h) provide incentives to providers of accessible technology solutions including software, hardware and applications

(i) take such measures that will lessen the burden of acquisition of accessible technologies and associated gadgets by PWDs through fiscal means such as tax exemptions, subsidization, funding acquisitions, etc.

(j) ensuring that licensed ICT service providers offer special tariff plans or discounted rates for persons with disabilities communicate with the rest of society.

(k) Ensure that licensed providers of telecommunications services make available services and supporting technologies for persons with disabilities including emergency services, accessible public phones and relay services to enable persons with speech, hearing and seeing disabilities

Similar sentiments were shared by lawyer and digital rights activist Angela Minayo, who said the workshop “was very productive” and had enabled participants to realise that there is a gap in the implementation of ICT policy and in awareness of how national policies and international legal frameworks provide for persons with disabilities to be able to access and use ICT.

Conversations from the workshop were carried forward to the KIGF, with a session on inclusion, where Okite joined Paul Kiage (Communications Authority), Nivi Sharma (BRCK), Ben Roberts (Liquid Telecom), Josephine Miliza (KICTANet) and Alfred Mugambi (Safaricom) on a panel.

Kiage, an assistant director in charge of the Universal Service Fund (USF), said the fund had collected KShs 9 billion (USD 86.6 million), mostly used to extend network coverage to areas without voice services and to offer broadband connection to 896 secondary schools across the 47 counties. He said they had installed JAWS software and other assistive devices in eight learning institutions, partnered with the National Council for Persons with Disabilities to create a portal to enable persons with disabilities to access information including job advertisements, and created platforms in some libraries to enable accessibility to digital content.

But, according to Okite, despite USF’s efforts, “the digital divide is growing bigger for persons with disabilities”. Research she was part of last year showed that computers in some of the learning institutions had not been replaced for several years, requisite software was not installed or out of date, and staff managing the labs were not trained to teach users. Sustainability of the initiative was thus in question.

Kiage’s response? “We could do a lot more because we know there’s even primary schools that are catering for persons with disabilities in Kenya so we could go lower and support such schools.”

As of March 2019, Kenya had a mobile penetration of 106%, or 51 million subscriptions, while internet subscriptions stood at 46.8 million, of which 46.7% were on broadband. But as the KIGF panel on inclusion heard, segments of Kenyans can not afford to use ICT, and those in rural areas, poor and uneducated women, and many persons with disabilities were cited.

Dr. Wairagala Wakabi of CIPESA asked the Kenya government to conduct a gap analysis to establish the unmet ICT needs of persons with disabilities, collect on a regular basis disaggregated data that shows how persons with different types of disabilities are using technology and the challenges hindering greater use, and invest a larger portion of universal service funds in promoting digital accessibility. He added that Kenya should grow awareness about assistive technologies and make these technologies affordable.

“We should leave no one behind when it comes to digital inclusion,” he said. “Clearly, the Communications Authority can do more to improve access for people with disabilities, including through the use of the Universal Service Fund,” he said.

The private sector needs to be compliant too, and to be held to account to fulfil its obligations. In Kenya, and indeed across Africa, Safaricom has been a pace-setter. Last November, it launched the DOT Braille Watch service to enable the use of its M-Pesa mobile money service by persons with disabilities, said Karimi Ruria, Public Policy Manager at the provider. In December 2017, Safaricom introduced the Interactive Voice Response (IVR) that enables visually impaired and blind customers to control their M-Pesa transactions.