By Byaruhanga Brian |

Ugandan journalists are increasingly facing intertwined physical and digital threats which intensify during times of public interest including elections and protests. These threats are compounded by internet shutdowns, targeted surveillance, account hacking, online harassment, and regulatory censorship that directly undermines their safety and work. A study on the Daily Monitor’s experience found that the 2021 general election shutdown constrained news gathering, data-driven reporting, and online distribution, effectively acting as digital censorship. These practices restrict news gathering, production, and dissemination and have been documented repeatedly from the 2021 general election through the run‑up to the 2026 polls.

Over the years, CIPESA has documented digital rights violations, challenged internet shutdowns, and worked directly with media practitioners to strengthen their ability to operate safely and independently. This work has deepened as the threats to journalism have evolved.

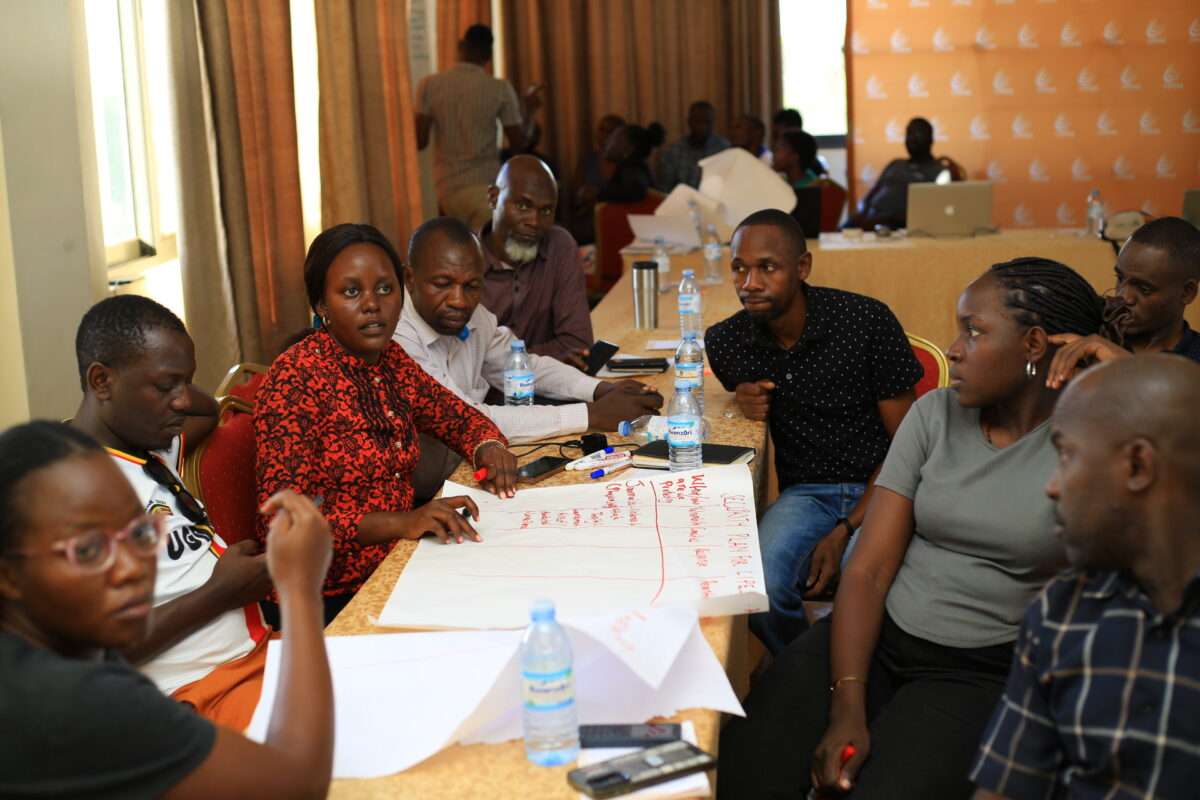

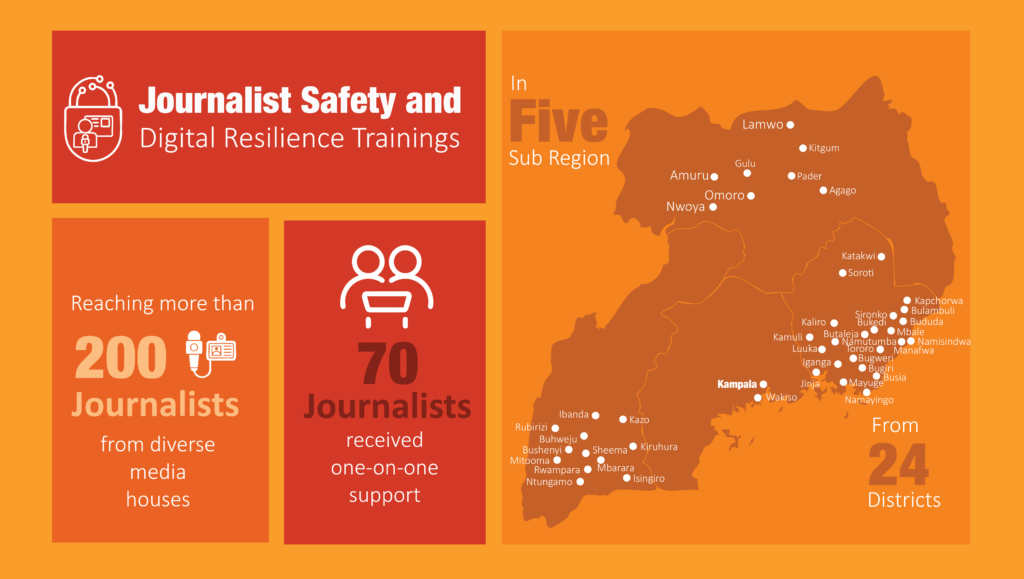

In recent months CIPESA has conducted extensive journalist safety and digital resilience trainings across the country, reaching more than 200 journalists from diverse media houses and districts across the country, in the Acholi subregion (Gulu, Kitgum, Amuru, Lamwo, Agago, Nwoya, Pader, and Omoro), Ankole sub region (Buhweju, Bushenyi, Ibanda, Isingiro, Kazo, Kiruhura, Mbarara (City & District), Mitooma, Ntungamo, Rubirizi, Rwampara, and Sheema), Central (Kampala, Wakiso), Busoga Region (Bugiri, Bugweri, Buyende, Iganga, Jinja, Kaliro, Kamuli, Luuka, Mayuge, Namayingo, and Namutumba), and the Elgon, Bukedi, and Teso subregions (Mbale, Bududa, Bulambuli, Manafwa, Namisindwa, Sironko, Tororo, Busia, Butaleja, Kapchorwa, Soroti, and Katakwi).

The trainings aimed to strengthen the capacity of media actors to mitigate digital threats and push back against rising online threats and censorship that enable digital authoritarianism. The training was central to helping journalists and the general media sector to understand media’s role in democratic and electoral processes, ensure legal compliance and navigate common restrictions, buttressing their digital and physical security resilience, enhancing the skills to identify and counter disinformation and facilitating the newsroom safety frameworks for the media sector.

The various trainings were tailored to respond to the needs of the journalists, covering media, democracy, and elections; electoral laws and policies; and peace journalism, with attention to transparent reporting and the effects of military presence on journalism in post-conflict settings.

Meanwhile, in Mbale and Jinja, reporters unpacked election-day risks, misinformation circulating on social media, and the legal boundaries that are often used to intimidate them. Across the different regions, newsroom managers, editors and reporters worked through practical exercises on digital hygiene, safer communication, and physical-digital risk intersections.

CIPESA’s digital security trainings respond to the real conditions journalists work under. The sessions focus on election-day and post-election reporting, verifying information and claims under pressure, protecting sources, and strengthening everyday digital security through strong passwords, two-factor authentication, and safe device handling. Journalists also develop newsroom safety protocols and examine how peace journalism can help de-escalate tension rather than inflame it during contested political moments

One of the most important shifts for the participants, came from the perspective that safety stopped being treated as an individual burden and started being understood as an organisational responsibility. Through protocol-development sessions, journalists mapped threats, identified vulnerabilities such as predictable routines and weak passwords, and designed “if-then” responses for incidents like account hacking, detention, or device theft. For many journalists, this was the first time safety had been written down rather than improvised.

Beyond the training for journalists, CIPESA hosted several digital security clinics and help desks for human rights defenders and activists. At separate engagements, close to 70 journalists received one-on-one support during a digital security clinic at Ukweli Africa held from the 15 December 2025 including the at the Uganda Media Week. These efforts sought to enhance their digital security practices. The support provided during these interventions included checking the journalists’ devices for vulnerabilities, removal of malware, securing accounts, enabling encryption, and secure data management approaches.

“Some journalists who had arrived unsure, even embarrassed, about their digital habits, left lighter, not because the risks had vanished, but because they now understood the tools and how to manage risks.”

These engagements serve as avenues to build the digital resilience of journalists in Uganda, especially as the media faces heightened online threats amidst a shrinking civic space.Such trainings that speak the language of lived experience often travel further than any policy alone. In Uganda, where laws can be used to narrow civic space, where the internet can be switched off, and where surveillance blurs the line between public and private, practical digital security becomes a necessity.

By training journalists across Uganda, supporting them through digital security desks, and standing with them during moments like Media Week, CIPESA has helped journalists strengthen their resilience to keep reporting in spite of the challenges and threats they encounter daily.