ICT Spring is a Global Tech Conference hosting an array of International Professionals. This two-day yearly event is held in Luxembourg City, at the heart of Europe, and offers the participants a unique opportunity to deepen their Digital Knowledge, capture the Value of the fast-growing FinTech Industry, and explore the impact of Space Technologies on Terrestrial Businesses.

You can click here for more details on the event., Digital Age

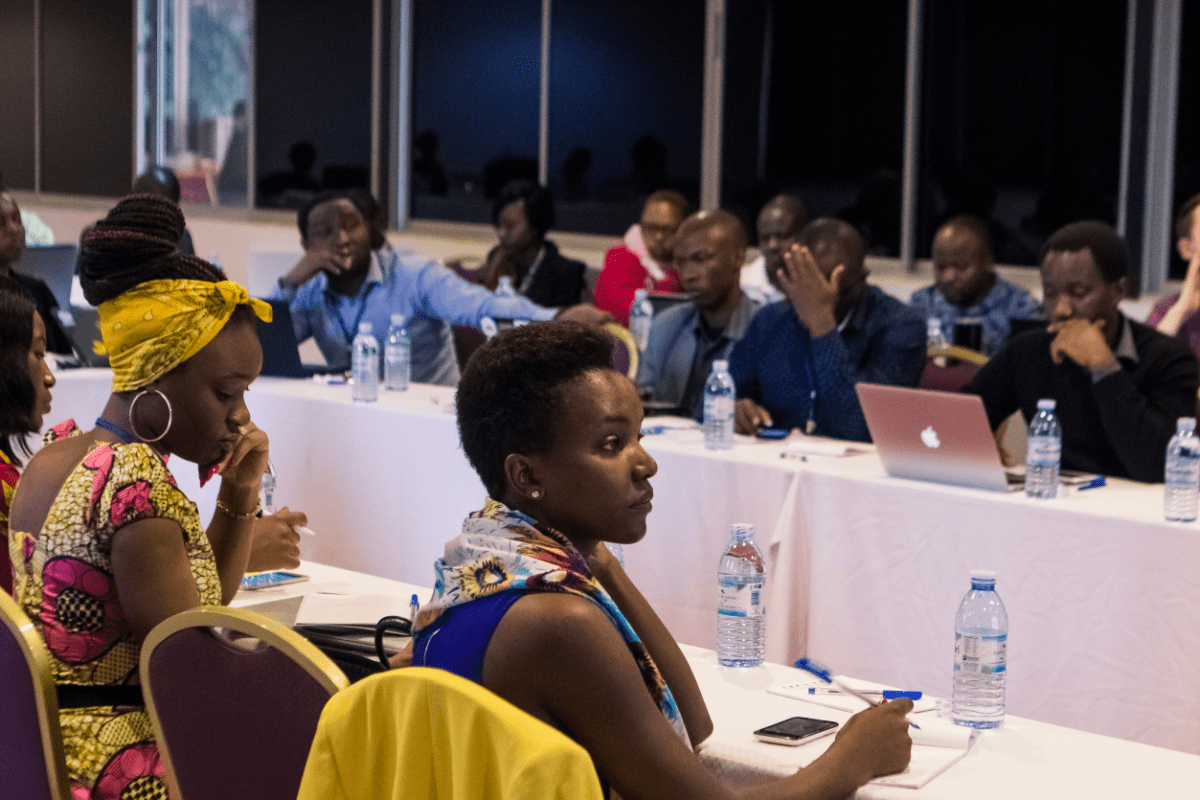

Building Collaborations in Research for Internet Policy Advocacy in Africa

By Juliet Nanfuka |

Many African countries are caught between developing policies that support the unfettered use of the internet as a tool for social, economic and political growth, and laws that threaten citizens’ rights and use of digital technologies. Often, this is partly due to limited evidence upon which to base policies and decision-making, which results from the scant availability of relevant in-depth research.

As the need for internet policy advocacy that is informed by research grows, it is essential to increase the amount and depth of research originating from Africa. It is equally necessary to expand the methods used beyond the traditional to more contemporary ones such as network measurements, social network analysis and data mining. This has led to the need to train, connect, and build collaboration between researchers, policy makers and internet freedom advocates across the region and formed the basis of an intensive training on internet policy research methods.

The training workshop, which was held between February 27 and March 3, 2018, was organised by the Annenberg School for Communication’s Internet Policy Observatory and the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA), alongside several partners from across Africa. A total of 40 participants from 17 countries attended the training in Kampala, Uganda. They included journalists, lawyers, technologists, academics, telecom regulators, government officials, and digital rights advocates.

The six days’ intensive curriculum covering various topics including on policy research, legal analysis, survey methods, social network analysis, strategic communication, data visualization, and network measurement was led by experts in the field, including faculty from Makerere University, University of San Francisco, the University of Pennsylvania, as well as various think tanks and civil society organisations.

The workshop emphasised the need to embrace more collaborative push back efforts such as strategic litigation, the deployment of tools such as the Ooni probe that monitor internet speed and performance, accompanied by social network analysis, data visualisation and data scraping which can reflect patterns of online narrative. It was also stressed that these methodologies, coupled with traditional research approaches through physical interactions such as focus group discussions and key informant interviews would support more multidisciplinary collaborations and versatile communication strategy for internet policy advocacy in Africa.

Indeed, evidence-based advocacy is fundamental today perhaps more than ever, as the affronts to citizen’s rights online continuously evolve, including at a technological infrastructure level (internet throttling, internet shutdowns, surveillance and data breaches), as well as laws and regulations that increasingly criminalise internet use. More recently, financial affronts to online content production and dissemination have been witnessed in Tanzania and Uganda.

The workshop alumni join a cohort of others from the Middle East, Asia, and Latin America equipped with the skills needed to collaborate across disciplinary and professional silos for progressive internet policy and practice at national, regional and global levels.

Below are some tweets shared from the workshop:

Less than 10% of local news sites in Africa are hosted locally. Exceptions include South Africa, Swaziland & Djibouti says @EnricoCalandro & @JosiahChavula . What are the implications for local news when it is not locally hosted? #InternetPolicyAfrica @cipesaug @InternetPolicyO

— Christopher Ali (@Ali_Christopher) February 28, 2018

https://twitter.com/kudathove/status/969500199486984192

Ooni: to understand what is blocked, how it’s being blocked and who is blocking it- it’s not just the data, but the interpretation and use of the data: “we need lawyers… we need policy makers… we need activists” @OpenObservatory @agrabeli_ #InternetPolicyAfrica @cipesaug pic.twitter.com/Ip8fGhTNx7

— Laura Schwartz-Henderson 🙃 (@LauraSHendo) February 28, 2018

https://twitter.com/kudathove/status/969125256911781889

#InternetPolicyAfrica via NodeXL https://t.co/9fqeWOk0xe@cipesaug@natabaalo

@internetpolicyo@elig_safrica@bashmutumba@afrosms@d_kandeh@kudathove@simply_omhle@ngamitaTop hashtags:#internetpolicyafrica#internetfreedomafrica#internetfreedom#uganda

— NodeXL Project (@nodexl) March 1, 2018

Data is not useful unless used as part of an action: policy makers, lawyers, journalists can analyze @OpenObservatory data to interpret socio-political developments. #InternetPolicyAfrica

— Digital Society Africa (@digisocAfrica) February 28, 2018

An interesting point being driven by @Mose_Karanja during the @OpenObservatory session is that http/https could make a difference in what's being blocked or not and by who. #InternetPolicyAfrica pic.twitter.com/DQ8zwgLDw8

— Ese (she/her) (@EseoheOjo) February 28, 2018

Internet measurement: 85% of local news websites are located outside of their respective countries (mostly Europe and US). #Africa #LocalContent #InternetPolicyAfrica pic.twitter.com/jPbSFoCEyL

— Blaise Ndola (@BlaiseNdola) February 28, 2018

https://twitter.com/NHLAKANHLANHLA/status/968457060424781824

Even if your strategic litigation efforts do not result in a significant societal/institutional change it is also a victory to spark dialogue and draw attention to your cause #InternetPolicyAfrica

— ELIG S.Africa (@ELIG_SAfrica) February 27, 2018

https://twitter.com/kudathove/status/968095031763652610

Understanding likely sources of justification for internet disruption in Zambia with @Mose_Karanja @OpenObservatory. A plug for mixed methods work drawing on measurements and legal research! #InternetPolicyAfrica @cipesaug pic.twitter.com/m4OTzue3bl

— Laura Schwartz-Henderson 🙃 (@LauraSHendo) February 27, 2018

Africa’s Internet of Things: Challenges and Opportunities

By Dorothy Mudavanhu |

The Forum on Internet Freedom in Africa 2016 served as an opportunity to gather insights from different stakeholders in the information society ecosystem towards promoting a free and safe internet. The platform was used to assemble the different perspectives and thoughts on the path that Internet Freedom should take in Africa. The Forum also gave stakeholders the opportunity to commemorate the International Day of Universal Access to Information held on September 28th every year.

There were fruitful deliberations around issues on transparency and accountability of intermediaries, internet shutdowns and internet rights, using data to track rights, working against normalisation of violence against women online, counting the cost of shutdowns and cyber security strategies for African countries, to name but a few.

Problems Highlighted

- There is a gender divide in access to ICT among women and men and a lack of policies for gender inclusion in ICT.

- Internet users are ignorant of how floating data is used hence the increase in cyber crime challenges such as fraud and online stalking.

- Crimes such as terrorism and hate speech existed long before digital platforms and in order to tackle them, cyber platforms in themselves should not be the problem governments seek to eliminate. Nonetheless, unclear jurisdictions for violators pose a challenge for law enforcement.

- More and more countries have seen the politicization and militarization of the cyber space as a means to control the free flow of information. This has seen an increase in internet shutdowns and attacks against freedom of expression, which comes at a high expense. Uganda’s two internet shutdowns during 2016 cost the economy an estimated $25 million, according to some estimates.

- Depsite privacy being a fundamental right, less than 20 countries in Africa have data protection laws.

- Who carries the burden of user awareness and understanding of terms of service for social media platforms? Users, service providers or the government? Where do we draw the line?

Positives highlighted

- Citizen awareness and engagement has increased through the use of ICT for participation in governance processes and social accountability.

- Countless businesses are dependent on digital platforms. States might/ will desist from shutdowns once they discover internet shutdowns come with an exorbitant cost to national revenue such as taxation.

- Internet penetration in Africa has increasingly bridged the gap between traditional and new media for citizens.

- Service providers such as Google, Facebook and Whatsapp are working to ensure safety and security of users for their products through innovations such as end-to-end encryption which decreases the chances of interception of communication, as well as community standards and reporting mechanisms.

Recommendations

- Continued lobbying and advocacy for access to the internet for all.

- Human rights-based approaches and principles should be integrated with campaigns for accessibility and inclusivity of the internet.

- There is need for citizens to invest more in media literacy as a way of protecting themselves against false news and misinformation.

- More media coverage of women’s voices and concerns related to the internet.

- Initiation of support spaces to work against online violence, particularly that directed against women. These spaces should be platforms for victims, and also send out positive message that deters violations online.

- Enactment and/or enforcement of all-encompassing cyber laws, through multistakeholder approach, that limit the powers of governments, ensure independent oversight, and uphold rights to privacy, among others.

- Due processes for lodging cyber complaints should be transparent, made easier and less time-consuming.

- Citizens’ access to information especially that held by governments is paramount. Civil society should take a leading role in engaging on information requests and disclosure.

- Regional cooperation should resolve issues on standardisation of ICT sectors including operator standards, market growth and quality of service.

The struggle for internet freedom calls for tenacious stakeholders that do not get weary until the global community realizes unfettered access to information.

This article was first published at Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum on October 10, 2016

Thanks to ICT, government secrets get ever fewer

By John Walubengo |

ICT IN POLITICS

What does the future hold for the Internet Governance Forum?

By Juliet N. Nanfuka

As the dust settles following the ninth Internet Governance Forum (IGF) which was held in Istanbul, Turkey between 2 and 5 September, many questions remain lurking. The biggest being whether the IGF has made a strong enough case for its continued existence. The IGF currently has a mandate that takes it until 2015. The United Nations (UN) General Assembly is due to take a decision about its renewal at the beginning of December 2014.

In keeping with the IGF’s core principle of multi-stakeholder engagement, the 9th Internet Governance Forum brought together an assortment of internet policy stakeholders including multinational organisations, state representatives, civil society and internet enthusiasts. The theme of this year’s IGF was “Connecting Continents for Enhanced Multi stakeholder Internet Governance” and was explored through the lens of net neutrality, multilingualism, youth and social media, gender, policy development, stakeholder roles and other related issues.

In a series of workshops, book launches and open sessions, internet policies were discussed and how they relate and impact upon society, development, business, governance and democracy. While there was agreement on some issues, divergence remained when it came to discussions on where monetising the internet clashed with big data, privacy, surveillance, intermediary liability and net neutrality.

This year’s meeting saw over 3,000 delegates from across the world convene in a country currently battling with some of the controversial internet related issues such as surveillance, censorship, privacy and data protection under discussion at the IGF. According to the 2013 Freedom on the Net report, nearly 30,000 websites and social media accounts are blocked in Turkey for social or political reasons. But Turkish bureaucrats deftly skirted these issues in their opening and closing speeches. While mention was made of the state of Turkish internet freedom by delegates, it mostly remained a rumbling in the underbelly of the meeting. However, some light on Turkey’s internet freedom status was heavily discussed at the Internet Ungovernance Forum organised by Turkish civil society organisations to protest the country’s hosting of the meeting given their government’s internet rights violations record.

For many participants, NetMundial was still a key talking point and formed the basis of some of the IGF’s discussions including promoting multilingualism, collaborative multi-stakeholder models, gender and internet rights, minority rights online, child online protection, privacy and surveillance and developing relevant local content. NetMundial demonstrated that multi-stakeholderism is possible and consensus can be drawn even on the most contentious internet governance topics (see NetMundial statement).

NetMundial sought to deliberate on the Future of Internet Governance by crafting Internet governance principles and proposing a roadmap for the further evolution of the Internet governance ecosystem.

Even though the IGF has for the past nine years provided a platform for the debate and deliberation on the very issues that NetMundial dealt with, there have been limited discernible outcomes and impact measurements due to the nature and complexity of internet governance and its actors.

However, much like the constantly transforming internet, the IGF will have to re-asses its financial sustainability model to ensure its survival and position itself as a driver of best practices on internet governance. Part of this includes the production of outcome documents such as policy recommendations for voluntary adoption – a suggestion put forward by the European Commission – a key funder of the IGF. Such actions could help shake off the ‘talk shop’ cloak that has shadowed the IGF and position it as a platform for deliberation on global internet governance concerns with more discernible outcomes.

The Tenth IGF is scheduled to take place in João Pessoa, Brazil on 10 to 13 November 2015.