Event |

Gender diversity in political leadership is critical for promoting equity, inclusion, and economic benefits. However, gender disparities in political participation still exist globally, particularly in Africa. Digital technologies can assist in solving this disparity given their ability to give voice and civic agency to different political actors, especially women, and space for political engagement. As enshrined in Sustainable Development Goal 5 on Gender Equality, digital technologies have the potential to increase women’s inclusion, participation, and engagement in politics, providing them with a platform to have their voices heard. Indeed, women in politics are increasingly leveraging the power of various digital tools, and in particular social media platforms, to connect with their constituencies.

Despite this reliance on online social platforms, women in politics have also become the targets of online threats and abuse. These attacks are heightened during election periods and when women voice dissenting opinions. This technology-facilitated gender-based violence (TFGBV) not only impedes women’s equitable and meaningful participation in public offices but also their long-term willingness to engage in public life. Further, it negatively influences the broader spectrum of women consuming or engaging with their content and consequently undermines the realization of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Addressing these challenges is essential to ensure that digital technologies become true enablers for the enhancement of women’s participation in democracy and good governance, including in politics, rather than exacerbating existing disparities in Africa.

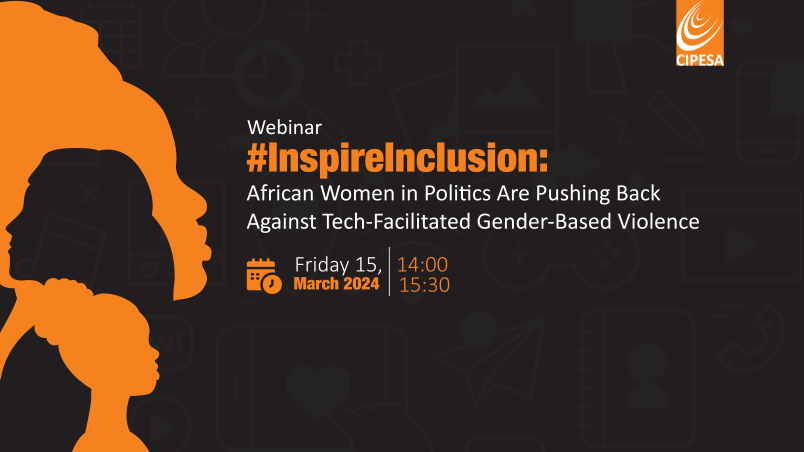

This month, we join the global community in celebrating women under the themes of #InspireInclusion, which encourages the realisation of a gender-equal world free of bias, stereotypes and discrimination. However, amidst the global celebration, it is crucial to spotlight the persistent TFGBV faced by African women in politics and the need to increase investment into addressing these concerns as highlighted by the United Nations campaign themed #InvestInWomen.

In an upcoming webinar, the Collaboration in International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) will focus on the importance of increased political inclusion of women in politics. The role of active online engagement will be highlighted as a key driver in enabling the needs of women in politics in various African countries and as a tool to meaningfully participate in the information society. More importantly, the webinar will cast a spotlight on how women in active politics in various African countries are pushing back against the violence and negative narratives online and the role that legal frameworks and platforms have to play in addressing TFGBV associated with political spaces and discourse.

Webinar details

Date: March 15, 2024

Time: 14:00-15:00 (Nairobi Time).

Register to participate in the webinar here.