By Patricia Ainembabazi |

The sixth edition of the Business and Human Rights Symposium in Uganda marked an essential step in Uganda’s journey to foster responsible and rights-respecting business conduct. Hosted on November 4-5, 2024, the symposium brought together over 200 participants from government, the private sector, academia, and civil society. It offered a platform to reflect on Uganda’s advancements in implementing its National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights and to consider newer frameworks such as the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD).

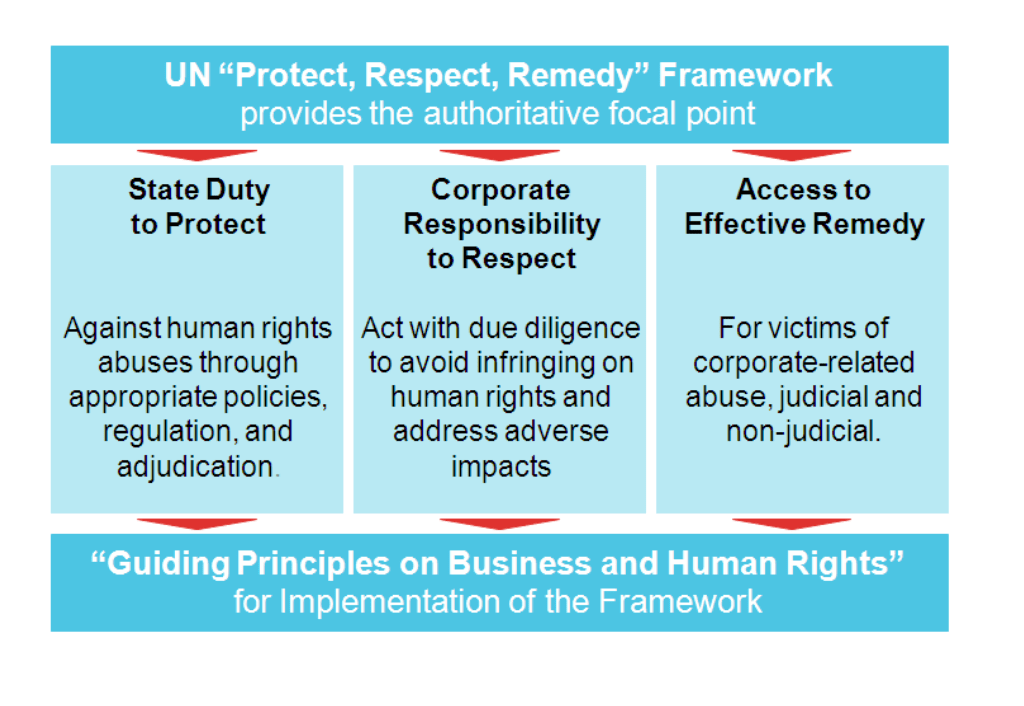

As part of the two-day proceedings, the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) hosted a panel discussion on the interplay between digital innovation and the protection of human rights, highlighting both successes and challenges in Uganda’s tech ecosystem. The panel discussed the United Nations (UN) Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and how they align with the technology sector.

Highlighting Uganda’s growing technology sector, including increased mobile and internet penetration as well as digitalisation of private and public services, the session also spotlighted pressing concerns, such as internet disruptions, labour rights violations, gender discrimination, and data protection and privacy, which continue to challenge human rights protections in the country’s growing digital economy.

Joel Basoga, Head of Technology Practice at H&G Advocates, stated that it was “essential” for businesses in Uganda to embed respect for human rights as a core performance indicator guided by the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. He added that for a tech-driven business landscape, legal frameworks surrounding digital rights need to be prioritised.

According to Patricia Ainembabazi, a Project Officer at CIPESA, there was limited understanding of business and human rights in the technology sector. Platforms such as the symposium were crucial in building a thematic understanding of digital rights.

In 2021, Uganda became the first African country to finalise a National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights (NAPBHR), based on the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. The plan strengthens the government’s duty to protect human rights, enhances the corporate responsibility to respect human rights, and ensures access to remedies for victims of human rights violations and abuses resulting from non-compliance by business entities.

In October 2024, CIPESA joined the first meeting of the Multi-Sectoral Technical Committee on Business and Human Rights, which supports the Uganda labour ministry’s role of coordinating the National Action Plan and provides technical guidance on all business and human rights interventions. At that meeting, CIPESA made the case for mainstreaming digital rights in the implementation of the action plan and also urged stakeholders to leverage innovative technologies to improve the outcomes of the action plan.

Similar to other countries in Africa, Uganda’s plan does not provide for digital rights protection, yet digital technologies have become central not only to how many businesses operate, but also to how individuals learn, work, socialise, and participate in community affairs. This increased digitalisation has had an impact on the ability of businesses to respect their human rights obligations.

| Objectives of Uganda’s National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights 1. To strengthen institutional capacity, operations and coordination efforts of state and non-state actors for the protection and promotion of human rights in businesses; 2. To promote human rights compliance and accountability by business actors; 3. To promote social inclusion and rights of the vulnerable and marginalised individuals and groups in business operations; 4. To promote meaningful and effective participation and respect for consent by relevant stakeholders in business operations; and 5. To enhance access to remedy to victims of business-related human rights abuses and violations in business operations. |

Speakers urged for increased cross-sector collaboration among stakeholders to align national frameworks more closely with the UN Guiding Principles. Opportunities for intervention include a push for robust data protection and privacy protections by the private sector; affordability of the internet and related technologies to ensure access to digital spaces; and raising awareness on digital rights roles and responsibilities for consumers and business owners. The symposium called upon stakeholders such as telecommunication companies, Internet Service Providers (ISP), financial institutions, innovators, and online platform operators to harmonise business goals with digital rights principles.

As part of the implementation of the NAPBHR, CIPESA is part of the newly launched Advancing Respect for Human Rights by Businesses in Uganda project led by Enabel and Uganda’s Ministry of Gender Labour and Social Development. The project is part of the European Union’s support towards the implementation of Uganda’s National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights and focuses on three thematic areas: labour rights in the agricultural sector, natural resource governance and land, and digital rights and internet governance. The project will work with six civil society organisations to drive advocacy, dialogue, and actions that strengthen Uganda’s Business and Human Rights agenda. Additionally, 50 businesses will receive support to implement human rights due diligence aligned with national and international standards.