By FIFAfrica |

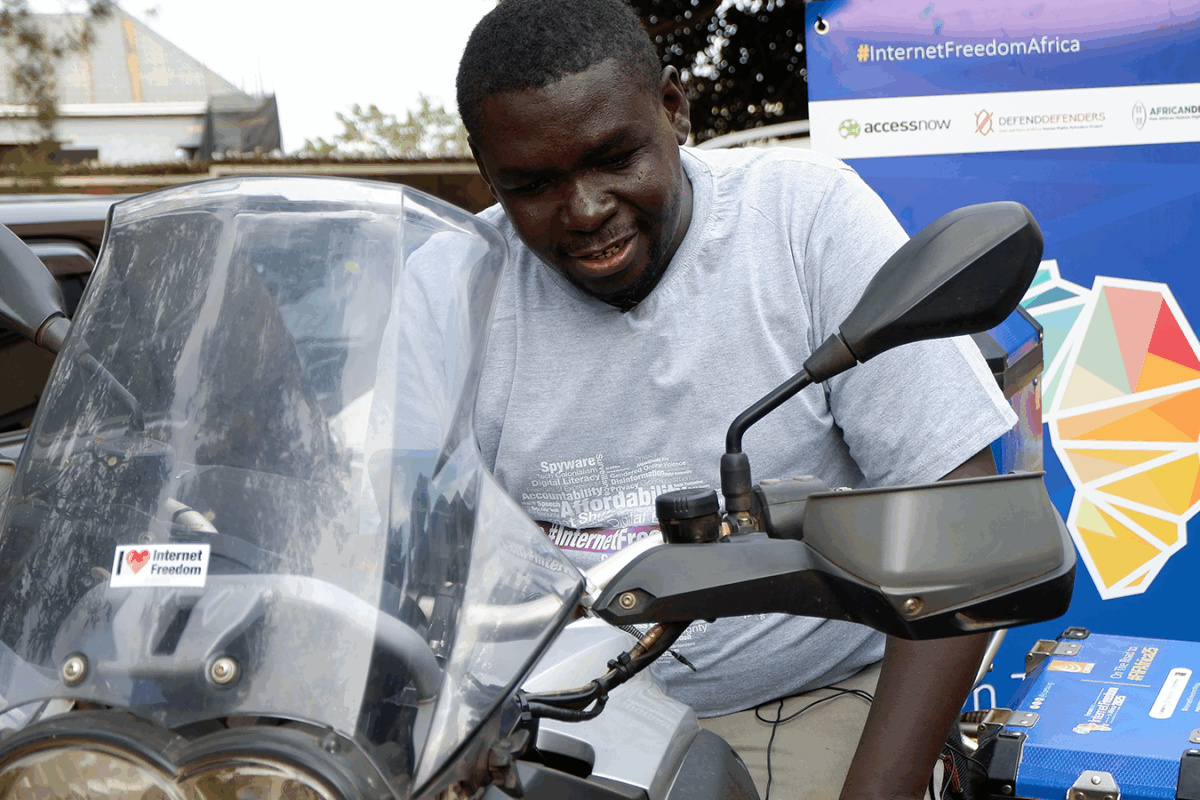

On Friday September 12, 2025, digital security expert and biker, Andrew Gole will set off on a solo motorbike journey spreading awareness about safety and security online. This will be the third time that Gole will travel across various countries on the continent ahead of the annual Forum on Internet in Africa (FIFAfrica). The effort is supported by the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA), Defend Defenders and Access Now.

Gole will commence his trip in Kampala, Uganda and over a round trip distance of 13,000 kilometers (km) traverse through Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Botswana, culminating in Windhoek, Namibia, where the 2025 edition of FIFAfrica will convene this September 24-26, 2025. On his return journey to Uganda, Gole will also ride through Zambia and Rwanda, making it a total of 10 countries travelled through over the course of the journey.

“I am truly excited to be hitting the road once again as part of the upcoming Forum on Internet Freedom in Africa. On my previous trips, I had the privilege of witnessing firsthand how diverse communities warmly embrace digital security as a key practice that empowers and protects their daily lives online and offline. These communities are often those left on the margins of mainstream efforts to enhance digital security, yet their eagerness to adopt these measures have been inspiring. I look forward to engaging with new communities on this trip and to continuing this important work and deepening these connections as we move forward together.” – Andrew Gole, Digital Security Expert

Gole notes that traveling on his motorbike allowed him the mobility to connect directly with grassroots organisations. His “Digital Security on Wheels” initiative started in 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic to address urgent digital security concerns beyond urban centers in Uganda and grew into a regional effort across East and Southern Africa through FIFAfrica.

In September 2022, ahead of the Forum which was held in Lusaka, Zambia and also served as the return to in-person meetings following a two year hiatus due to Covid-19, Gole pioneered the the #RoadToFiFAfrica Digital Security campaign. Gole embarked on the ambitious solo motorbike journey traversing approximately 3,300 kilometers.

The following year in 2023, ahead of the Tanzania edition of FIFAfrica, Gole led a major expedition that involved a team doing a round trip covering almost 10,000 km from Uganda through Kenya to Tanzania (and into the Indian Ocean island of Zanzibar via ferry). Gole was once again on his motorbike, supported by a team of digital rights experts from the Defenders Protection Initiative (DPI) in a passenger van.

“We applaud Gole’s effort and celebrate the spirit he carries every mile to Windhoek. Andrew’s ride is a testament to the ongoing effort of building Africa’s internet freedom community. It embodies the practical, peer-led approach to digital safety that empowers often-overlooked communities. His journey to Windhoek mirrors CIPESA’s core mission of promoting the inclusive and effective use of ICT for improved governance and livelihoods in Africa. Gole’s remarkable endurance underscores that protecting our digital spaces demands mobility, resilience, and solidarity. We applaud his effort as he carries this message all the way from Kampala to Windhoek.”

– Brian Byaruhanga, Technology Officer, CIPESA

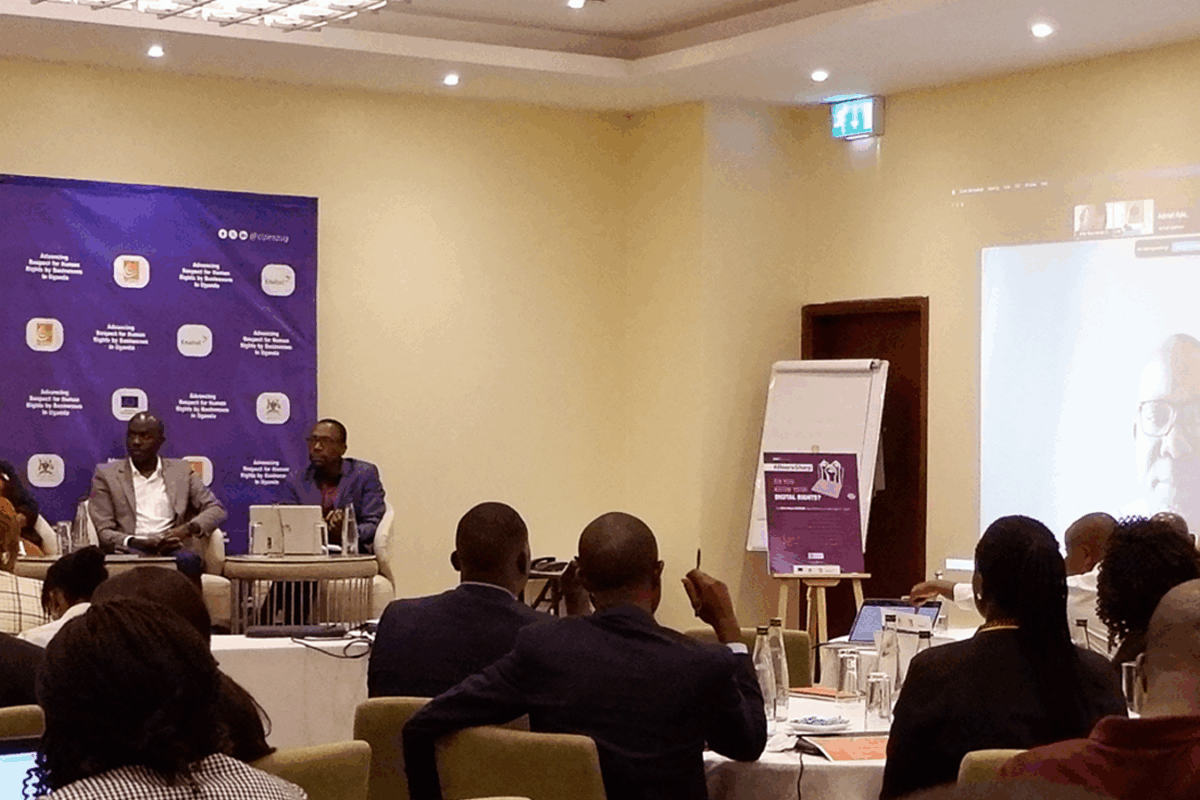

In all instances, Gole’s efforts culminated in the Digital Security Hub that has become a staple at FIFAfrica and serves as a one-stop-shop for attendees online and offline to secure their devices while also attaining practical skills and information on how to navigate online spaces safely.

The Digital Security Hub convened by CIPESA has featured experts from across the world and this year will include experts from Africa Interactive Media, Base Iota, Co-creation HUB, Defenders Protection Initiative (DPI), Digital Society Africa, Greenhost/Frontline Defenders and Defend Defenders alongside SocialTic, and Foundacion Accesso bringing learnings and expertise from South America.

About the Forum on Internet Freedom in Africa: Now in its 12th year, the annual Forum on Internet Freedom in Africa (#FIFAfrica25) is the continent’s leading platform for shaping digital rights, inclusion, and governance conversations. This year, the Forum will be held in Windhoek, Namibia, a beacon of press freedom, gender equity, and progressive jurisprudence, and is set to take place on September 24–26, 2025.

FIFAfrica offers a unique, multi-stakeholder platform where key stakeholders, including policymakers, journalists, global platform operators, telecommunications companies, regulators, human rights defenders, academia, and law enforcement representatives convene to deliberate and craft rights-based responses for a resilient and inclusive digital society for Africans.

FIFAfrica25 will be the third edition to be hosted in Southern Africa. Previous editions have been hosted in Uganda, South Africa, Ghana, Ethiopia, Zambia, Tanzania and Senegal. Namibia, with its strong democratic credentials and progressive stance on digital transformation, provides a fitting host for FIFAfrica25.

About the Digital Security Hub: At the heart of FIFAfrica has been a Digital Security Hub designed to equip participants with practical knowledge and tools for staying safe in an increasingly digital environment. The Hub offers practical demonstrations and expert guidance on how to strengthen digital safety and resilience practices.

The Hub serves as a meeting for digital security trainers, technologists, and frontline users from across Africa and this year, Latin America as well. Digital security practices shared by the teams include advice on encryption and secure communications, through to countering online harassment and building safer digital infrastructures.

The Digital Security hub is a vital feature of FIFAfrica25 and continues to serve as a space where communities can tangibly build their capacity to navigate the constantly evolving digital ecosystem.

About the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA): CIPESA works to promote inclusive and effective use of Information and Communication Technology. (ICT) in Africa for improved governance and livelihoods. CIPESA was established in 2004 in response to the findings of the Louder Voices Report for the UK’s then Department for International Development (DFID), which cited the lack of easy, affordable and timely access to information about ICT-related issues and processes as a key barrier to effective and inclusive ICT policy making in Africa. CIPESA’s work continues to respond to a shortage of information, resources and actors consistently working at the nexus of technology, human rights and society.

Initially set up with a focus on research in East and Southern African countries, CIPESA has since expanded its work to include advocacy, capacity development and movement building across the African continent.

Today CIPESA is a leading ICT policy and governance think tank in Africa. CIPESA has strongly exhibited its passion about raising the capacity of African stakeholders in effective ICT policy making and in engendering ICT in development and poverty reduction, as per its mandate.

For Queries about CIPESA and the Digital Resilience Hub