By Juliet Nanfuka |

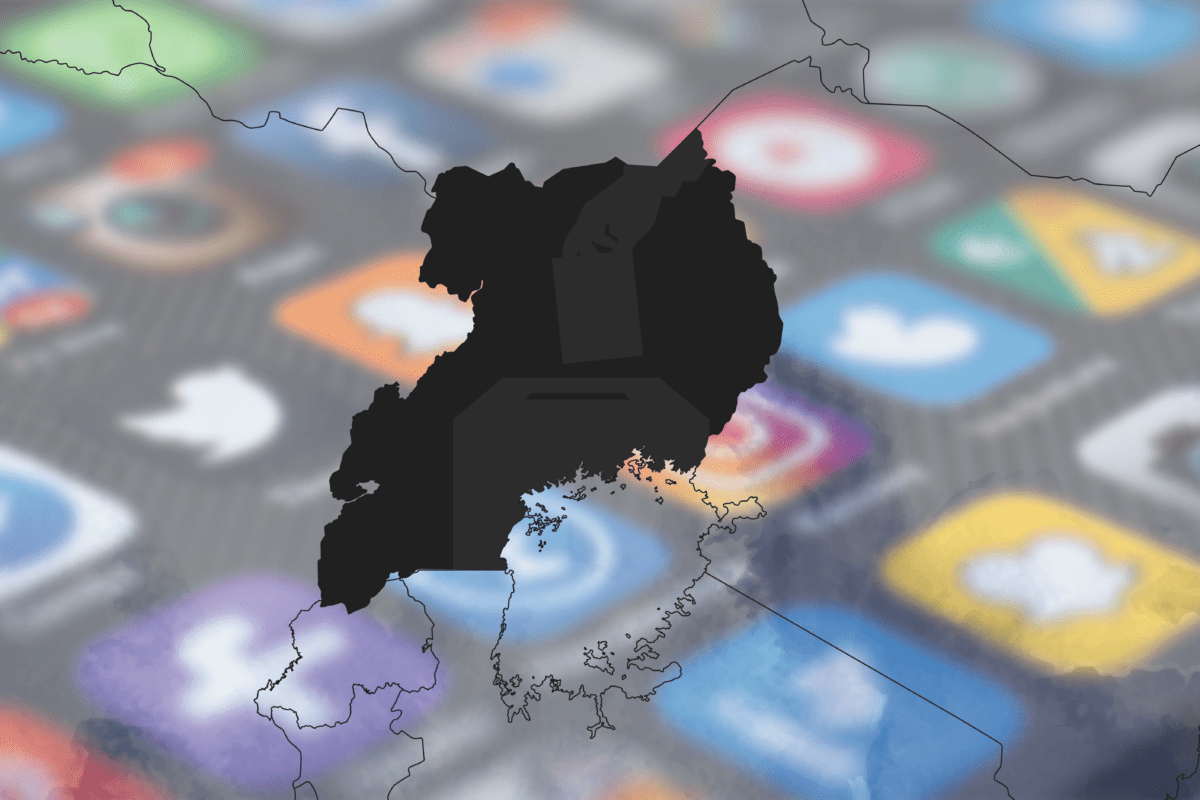

In two days, as Uganda heads to its presidential and parliamentary elections slated for January 15, 2026, citizens, civil society actors, journalists, and digital rights defenders were stumped with the question, “will they shut down the internet again?” Or, this time, will we see a commitment to adherence to one of the basic fundamentals of digital democracy and have an election in which access to digital communications remains open?

In recent weeks, anxiety about an impending internet blackout has surged despite Dr. Aminah Zawedde, Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of ICT and National Guidance, and Hon. Nyombi Thembo, Executive Director of the Uganda Communications Commission (UCC), dismissing rumours of plans to shut down the internet, calling them “false and misleading”.

However, for many, these pronouncements have done little to quell suspicions, especially due to the actions witnessed during the 2016 and 2021 elections. During those previous two elections, access to digital communications was restricted, resulting in a block to online communication, commerce, and key avenues for civic engagement.

Various actions in the lead up to the polls have also served to compound the suspicions. In a report issued in January 2026, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) describes the arrests of state critics as “arbitrary and discriminatory” and outside of the country’s constitutional guarantees.

“Despite the strong constitutional protection of rights, the human rights situation in Uganda during the period under review has been characterized by increasingly restrictive legislation and their arbitrary and discriminatory application. The Government of Uganda has continued to rely on legislation such as the Public Order Management Act (POMA), the Anti-Terrorism Act, the NGO Act, the Computer Misuse (Amendment) Act and the Penal Code Act to shrink civic and democratic space and further weaken political participation, particularly of political opponents and their supporters, as well as the work of civil society, including journalists and human rights defenders.” OHCHR Report on Uganda

Meanwhile, independent media has come under increasing pressure, experiencing various forms of clampdowns in the lead up to the elections, including the denial of advertising spend. In October 2025, independent outlets – NTV Uganda and The Daily Monitor – were denied accreditation to cover parliamentary and presidential proceedings. Reports of harassment, equipment confiscation as well as attacks on journalists during election campaign coverage, and raids on media offices, have been commonplace – underscoring a deteriorating environment for media freedom.

Meanwhile the satellite internet provider Starlink, which has services that can operate independently of terrestrial networks, was halted in Uganda after a regulatory directive in early January 2026, rendering all Starlink terminals inactive ahead of polling day. The satellite internet service provider was providing services without a valid local license. Critics still argue that the directive serves to limit alternatives for connectivity in the event of broader restrictions on internet access, feeding anxieties about reduced access to independent channels of information.

The UCC has also come under fire following its warning to broadcasters and digital content creators against live coverage of riots, protests, or incidents that could disrupt public order. The regulator stated that only the Electoral Commission may declare election results, and sharing unverified results is illegal. Dr. Zawedde stated, “Media platforms must not be abused to incite violence, spread misinformation, or undermine the credibility of the electoral process.”

By the afternoon of January 13, 2026, a directive circulating online had been issued by UCC to mobile network operators to block public access to the internet, effective at 18:00.

In a public statement, Access Now and the global #KeepItOn coalition had urged President Yoweri Museveni and relevant national authorities to ensure unrestricted internet access throughout the electoral period and to refrain from any disruptive measures that impede the free flow of information. The statement stresses the fundamental role that connectivity plays in inclusive participation, freedom of expression, and the credibility of the electoral process.

Likewise, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) also reaffirmed that internet access is a core human right and a necessary condition for free and fair elections, warning against restrictions that would stifle civic space. The Commission called on the Government of Uganda to ratify the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance, signed on January 27, 2013, which emphasises the importance of a culture of peaceful change of power based on regular, free, fair and transparent elections conducted by competent, independent and impartial electoral bodies.

For democracy to flourish in Uganda, authorities must demonstrate their commitment to open digital spaces. This means not only publicly guaranteeing uninterrupted internet access before, during, and after the elections but also building trust through transparency and accountability. Citizens deserve to communicate freely, monitor the electoral process, and hold all actors accountable without fear of arbitrary disruption.

Ultimately, Uganda’s electoral credibility will not be judged by what happens at polling stations, but by whether the state resists the temptation to control information by disrupting digital access. In an era where civic participation, journalism, election transparency, and even livelihoods heavily rely on digital access, a disruption would signal a fear of accountability.

If the government chooses restraint in the coming hours, it would mark a major departure from a troubling past and offer Ugandans a rare assurance in the election process. If it does not, history will record yet another election where the digital access was shut down to presumably manage dissent rather than protect democracy.