By Nwachukwu Egbunike |

Africa’s landscape of online free speech and dissent is gradually, but consistently, being tightened. In legal and economic terms, the cost of speaking out is rapidly rising across the continent.

While most governments are considered democratic in that they hold elections with multi-party candidates and profess participatory ideals, in practice, many operate much closer dictatorships — and they appear to be asserting more control over digital space with each passing day.

Cameroon, Tanzania, Uganda, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Benin have in the recent past witnessed internet shutdowns, the imposition of taxes on blogging and social media use, and the arrest of journalists. Media workers and citizens have been jailed on charges ranging from publishing “false information” to exposing state secrets to terrorism.

At the recent Forum of Internet Freedom in Africa (FIFA) held in Accra, Ghana, a group of panelists from various African countries all said they feared African governments were interested in controlling digital space to keep citizens in check.

Many countries have statutes and laws which guarantee the right to free expression. In Nigeria, for example, the Freedom of Information Act grants citizens the right to demand information from any government agency. Section 22 of the 1999 Constitution provides for freedom of the press and Section 39 maintains that “every person shall be entitled to freedom of expression, including the freedom to hold and to receive and impart ideas and information without interference…”

Yet, Nigeria has issued other laws that authorities use to deny these aforementioned rights.

Section 24 of Nigeria’s Cybercrime Act criminalises “anyone who spreads messages he knows to be false, for the purpose of causing annoyance, inconvenience, danger, obstruction, insult, injury, criminal intimidation, enmity, hatred, ill will or needless anxiety to another or causes such a message to be sent.”

Making laws with ambiguous and subjective terms like “inconvenience” or “insult” calls for concern. Governments and their agents often use this as a cover to suppress freedom of expression.

Who determines the definition of an insult? Should public officials expect to develop a thick skin? In many parts of the world, citizens have the right to criticise public officials. Why don’t Africans have the right to offend as an essential part of free expression?

In 2017 and 2016, Nigerian online journalists and bloggers Abubakar Sidiq Usman and Kemi Olunloyo were each booked on spurious charges of cyber-stalking in connection with journalistic investigations on the basis of the Cybercrime Act.

Don’t suffer in silence — keep talking

The very existence of these legal challenges tells citizens that their voices matter. From Tanzania’s prohibition on spreading “false, deceptive, misleading or inaccurate” information online to Uganda’s tax on social media that is intended to curb “gossip”, the noise made on digital platforms scares oppressive regimes. In some cases, it may even lead to them to rescind their actions.

The experience of the Zone9 bloggers of Ethiopia provides a powerful example.

In 2014, nine Ethiopian writers were jailed and tortured over a collective blogging project in which they wrote about human rights violations by Ethiopia’s former government, daring to speak truth to power. The state labeled the group “terrorists”for their online activity and incarcerated them for almost 18 months.

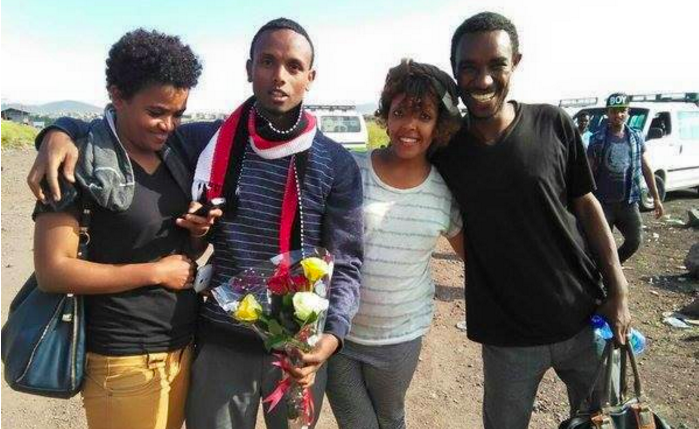

Zone9 members Mahlet (left) and Zelalem (right) rejoiced at the release of Befeqadu Hailu (second from left, in scarf) in October 2015. Photo shared on Twitter by Zelalem Kiberet.

Six members of the now liberated group made their premier international engagement in Ghana during FIFA conference: Atnaf Berhane, Befeqadu Hailu Techane, Zelalem Kibret, Natnael Feleke Aberra, and Abel Wabella were all in attendance. Jomanex Kasaye, who had worked with the group prior to the arrests (but was not arrested) also attended.

Several members had collaborated with Global Voices to write and translate stories into the Amharic. As members of the community, Global Voices campaigned and mobilised the global human rights community to speak out about their case from the very first night they were arrested.

After months of writing stories and promoting their case on Twitter, international condemnation of their arrest and imprisonment began to flow from governments and prominent human rights leaders, alongside hundreds of thousands of online supporters. From the four-compass points of the world, a mighty cry arose demanding the Ethiopian government to free the Zone9 bloggers.

In their remarks at FIFA, the bloggers said that their membership in the Global Voices community was key to visibility during their time in prison. In their panel session, they credited Global Voices’ campaign for keeping them alive.

Berhan Taye, the panel moderator, asked the group to recount their prison experiences. As they spoke, the lights on the stage dimmed. Their voices filled the room with a quiet power.

Abel Wabella, who ran Global Voices’ Amharic site, lost hearing in one ear due to the torture he endured after refusing to sign a false confession.

Atnaf Berhane recalled that one of his torture sessions lasted until 2 a.m. and then continued after he had a few hours of sleep.

One of the security agents who arrested Zelalem Kibret had once been Kibret’s student at the university where he taught.

Jomanex Kasaye recounted the mental agony of leaving Ethiopia before his friends were arrested — the anguish of powerlessness — the unending suspense and fear that his friends would not make it out alive.

Zone9 bloggers together in Addis Ababa, 2012. From left: Endalk, Soleyana, Natnael, Abel, Befeqadu, Mahlet, Zelalem, Atnaf, Jomanex. Photo courtesy of Endalk Chala.

With modesty, the Zone9 bloggers said: “We are not strong or courageous people…we are only glad we inspired others.”

Yet, the Zone9 bloggers redefined patriotism with both their words and actions. It takes immense courage to love one’s country even after suffering at its hands for speaking out.

Ugandan journalist Charles Onyango-Obbo, also in attendance at FIFA, shared an Igbo proverb popularised by Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe which says:

Since the hunter has learned to shoot without missing, Eneke the bird has also learnt to fly without perching.

In essence, he meant that in order to keep digital spaces free and safe, those involved in this struggle must devise new methods.

Activists on the front lines of free speech in sub-Saharan Africa and across the globe cannot afford to work in silos or go silent in frustration and defeat. With our strength and unity, online spaces will remain free to deepen democracy through vibrant dissent.