By Anitah Ahebwa |

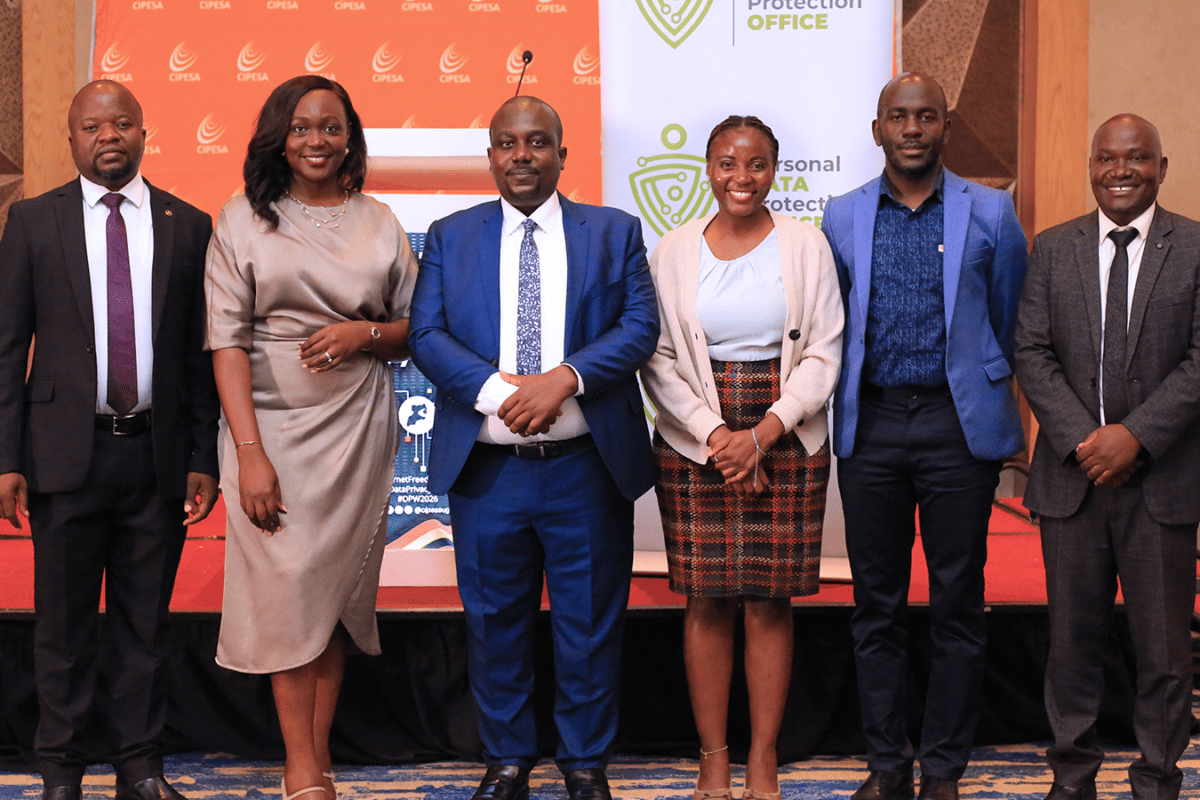

Data Protection Officers (DPOs) from across the country gathered at Four Points by Sheraton, Kampala, on Wednesday, 28 January 2026, for a masterclass aimed at strengthening strategic data protection leadership. Organised by the Personal Data Protection Office (PDPO) in partnership with the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA), the event marked the annual International Data Privacy Day and focused on helping DPOs balance compliance, risk, and business needs within their organisations.

While giving opening remarks at the masterclass, Baker Birikujja, the National Personal Data Protection Director, highlighted the everyday realities of personal data protection.

“Some of the most damaging privacy incidents do not begin with hackers,” he said. “They begin with a printed report left on a desk, a patient file discussed in an open corridor, an unlocked cabinet, or a phone call handled without discretion. Personal data exists not only online, but on paper, in recordings, photographs, CCTV footage, and everyday conversations and it deserves the same discipline and respect wherever it sits.”

He added that modern privacy management is not merely a file of policies. “It is a system of decisions, behaviors, controls, and accountability,” he said, noting that effective data protection requires attention to both digital environments such as databases, apps, and cloud services, and physical or offline environments, including paper records, filing systems, CCTV, and call recordings.

Edrine Wanyama, Programme Manager Legal at CIPESA, noted that the partnership with the PDPO was driven by a shared commitment to building strong and effective collaborations in data governance and protection. “We believe in building good partnerships, and we have actively leveraged and worked through these processes to buttress efforts,” he said. He added that data protection is central to CIPESA’s work.

He further noted that marking International Data Privacy Day through the workshop was intentional, explaining that the masterclass was designed to enhance knowledge of Data Protection Officers and build their capacity to effectively respond to emerging data protection risks and take appropriate actions

Edrine Wanyama, Programme Manager, Legal at CIPESA, explained why CIPESA partnered with PDPO; “We believe in building strong partnerships and have leveraged these collaborations over time. Data protection is central to what we do, and data is critical because it relates directly to individuals.”

He also highlighted that the timing of the masterclass on International Data Privacy Day was intentional. He noted that the workshop was designed to bring Data Protection Officers together to not only acquire knowledge but also build their capacity to effectively do their work.

The masterclass featured three key sessions. The first explored the evolving role of the DPO as a strategic advisor, covering legal mandates, independence, and repositioning from a compliance officer to a trusted advisor. The second session focused on applying a risk-based approach to data protection, helping DPOs identify high-risk processing activities, prioritise compliance actions, and use risk assessments to guide management decisions. The final session addressed balancing compliance, risk, and business needs, equipping DPOs with strategies to advise leadership in clear business language, support innovation, and document recommendations effectively.

The sessions come against a backdrop of broader challenges for DPOs in Uganda. A recent PDPO training needs assessment conducted by the PDPO in November 2022, revealed that around 90.6% of DPOs lack formal certification in data protection and privacy, and only a small proportion have technical or legal backgrounds. Many officers are also less involved in core compliance tasks such as audits, breach reporting, and managing data protection complaints. These findings highlight the continued importance of professional development and knowledge-sharing forums like this masterclass.

By convening DPOs on International Data Privacy Day, PDPO and CIPESA emphasised the need for proactive privacy leadership in safeguarding personal data and maintaining public trust. Participants were equipped with practical tools to advise management, manage data protection risks, and integrate privacy considerations into organisational practices.

The masterclass is part of PDPO’s ongoing efforts to foster a culture of responsible data governance in Uganda, ensuring that personal data protection extends beyond regulatory compliance to build public confidence in the country’s growing digital economy.

Following the sessions, participants agreed on collective actions to:

- Prioritise privacy-by-design and continually engage in robust cybersecurity practices aimed at protecting and securing individuals’ personal data.

- Develop internal data protection policies to guide the implementation of data practices and ensure personal data protection.

- Keep abreast of technological developments, including AI, and ensure minimisation of risks associated with it for progressive data protection.

- Conduct staff and customer tailored trainings and raise awareness amongst them on data protection and the need to safeguard their data.

- Ensure that as DPOs, they take on pivotal leadership over data protection to ensure compliance with the data protection principles and protection of data protection rights.

- Hold all perpetrators of data breaches accountable for their actions in order to deter any further similar breaches by errant data controllers and processors.

- Conduct regular data mapping and maintain up-to-date records of processing activities to understand what data is in their possession and how to rightly handle it in the changing technological and business spaces.

- Foster collaboration across teams and recognise that privacy cannot be managed in isolation but through joint responsibility and efforts.

- Recognise their central role in the compliance and reporting function to ensure the establishment of safeguards that protect their organisations from reputational, legal, and financial harms.

Please see an emerging press release here.