By Brian Byaruhanga

In June 2025, Uganda suspended its Express Penalty Scheme (EPS) for traffic offences, less than a week after its launch, citing a “lack of clarity” among government agencies. While this seemed like a routine administrative misstep, it exposed a more significant issue: the brittle foundation upon which many digital public infrastructures (DPI) in Africa are being built. DPI refers to the foundational digital systems and platforms, such as digital identity, payments, and data exchange frameworks, which form the backbone of digital societies, similar to how roads or electricity function in the physical world.

This EPS saga highlighted implementation gaps and illuminated a systemic failure to promote equitable access, public accountability, and safeguard fundamental rights in the rollout of DPI.

When the State Forgets the People

The Uganda EPS, established under section 166 of the Traffic and Road Safety Act, Cap 347, serves as a tech-driven improvement to road safety. Its goal is to reduce road accidents and fatalities by encouraging better driver behaviour and compliance with traffic laws. By allowing offenders to pay fines directly without prosecution, the system aims to resolve minor offences quickly and to ease the burden on the judicial system. Challenges faced by the manual EPS system, which the move to the automated system aimed to eliminate, include corruption (reports of deleted fines, selective enforcement, and theft of collected penalties).

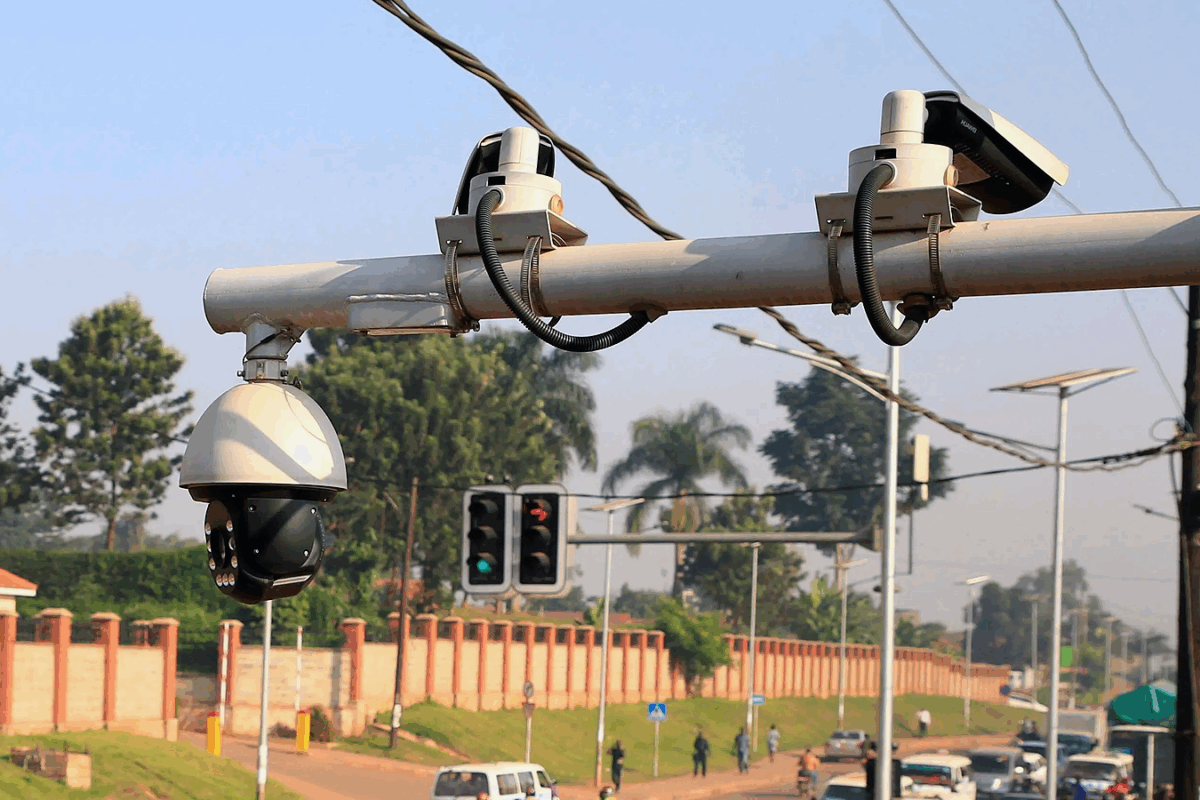

At the heart of the EPS was an automated surveillance and enforcement system, which used Closed Circuit Television (CCTV) cameras and license plate recognition to issue real-time traffic fines. This system operated with almost complete opacity. A Russian company, Joint Stock Company Global Security, was reportedly entitled to 80% of fine revenues, despite making minimal investment, among other significant legal and procurement irregularities. There was a notable absence of clear contracts, publicly accessible oversight mechanisms, or effective avenues for appeal. Equally concerning, the collection and storage of extensive amounts of sensitive data lacked transparency regarding who had access to it.

Such an arrangement represented a profound breach of public trust and an infringement upon digital rights, including data privacy and access to information. It illustrated the minimal accountability under which foreign-controlled infrastructure can operate within a nation. This was a data-driven governance mechanism that lacked the corresponding data rights safeguards, subjecting Ugandans to a system they could neither comprehend nor contest.

This is Not an Isolated Incident

The situation in Uganda reflects a widespread trend across the continent. In Kenya, the 2024 Microsoft–G42 data centre agreement – announced as a partnership with the government to build a state-of-the-art green facility aimed at advancing infrastructure, research and development, innovation, and skilling in Artificial Intelligence (AI) – has raised serious concerns about data sovereignty and long-term control over critical digital infrastructure.

In Uganda, the National Digital ID system (Ndaga Muntu) became a case study in how poorly-governed DPI deepens structural exclusion and undermines equitable access to public services. A 2021 report by the Centre for Human Rights and Global Justice found that rigid registration requirements, technical failures, and a lack of recourse mechanisms denied millions of citizens access to healthcare, education, and social protection. Those most affected were the elderly, women, and rural communities. However, a 2025 High Court ruling ignored evidence and expert opinions about the ID system’s exclusion and implications for human rights.

Studies estimate that most e-government projects in Africa end in partial or total failure, often due to poor project design, lack of infrastructure, weak accountability frameworks, and insufficient citizen engagement. Many of these projects are built on imported technologies and imposed models that do not reflect the realities or governance contexts of African societies.

The clear pattern is emerging across the continent: countries are integrating complex, often foreign-managed or poorly localised digital systems into public governance without establishing strong, rights-respecting frameworks for transparency, accountability, and oversight. Instead of empowering citizens, this version of digital transformation risks deepening inequality, centralising control, and undermining public trust in government digital systems.

The State is Struggling to Keep Up

National Action Plans (NAPs) on Business and Human Rights, intended to guide ethical public–private collaboration, have failed to address the unique challenges posed by DPI. Uganda’s NAP barely touches on data governance, algorithmic harms, or surveillance technologies. While Kenya’s NAP mentions the digital economy, it lacks enforceable guardrails for foreign firms managing critical infrastructure. In their current form, these frameworks are insufficiently equipped to respond to the complexity and ethical risks embedded in modern DPI deployments.

Had the Ugandan EPS system been subject to stronger scrutiny under a digitally upgraded NAP, key questions would likely have been raised before implementation:

- What redress exists for erroneous or abusive fines?

- Who owns the data and where is it stored?

- Are the financial terms fair, equitable, and sovereign?

But these questions came too late.

What these failures point to is not just a lack of policy, but a lack of operational mechanisms to design, test and interrogate DPI before roll out. What is needed is a practical bridge that responds to public needs and enforces human rights standards.

Regulatory Sandboxes: A Proactive Approach to DPI

DPI systems, such as Uganda’s EPS, should undergo rigorous testing before full-scale deployment. In such a space, a system’s logic, data flows, human rights implications, and resilience under stress are collectively scrutinised before any harm occurs. This is the purpose of regulatory sandboxes – platforms that offer a structured, participatory, and transparent testbed for innovations.

Thus, a regulatory sandbox could have revealed and resolved core failures of Uganda’s EPS before rollout, including the controversial revenue-sharing arrangement with a foreign contractor.

How Regulatory Sandboxes Work: Regulatory sandboxes are useful for testing DPI systems and governance frameworks such as revenue models in a transparent manner, enabling stakeholders to examine the model’s fairness and legality. This entails publicly revealing financial terms to regulators, civil society, and the general public. Secondly, before implementation, simulated impact analyses can also highlight possible public backlash or a decline in trust. Sandboxes can be used for facilitating pre-implementation audits, making vendor selection and contract terms publicly available, and conducting mock procurements to detect errors. By defining data ownership and access guidelines, creating redress channels for data abuse, and supporting inclusive policy reviews with civil society, regulatory sandboxes make data governance and accountability more clear.

This shift from reactive damage control to proactive governance is what regulatory sandboxes offer. If Uganda had employed a sandbox approach, the EPS system might have served as a model for ethical innovation rather than a cautionary tale of rushed deployment, weak oversight, and lost public trust.

Beyond specific systems like EPS or digital ID, the future of Africa’s digital transformation hinges on how digital public infrastructure is conceived, implemented, and governed. Foundational services, such as digital identity, health information platforms, financial services, surveillance mechanisms, and mobility solutions, are increasingly reliant on data and algorithmic decision-making. However, if these systems are designed and deployed without sufficient citizen participation, independent oversight, legal safeguards, and alignment with the public interest, they risk becoming tools of exclusion, exploitation, and foreign dependency.

Realising the full potential of DPIs as a tool for inclusion, digital sovereignty, and rights-based development demands urgent and deliberate efforts to embed accountability, transparency, and digital rights at every stage of their lifecycle.

Photo Credit – CCTV system in Kampala, Uganda. REUTERS/James Akena (2019)