FIFAfrica22 |

Digital biometric data collection programmes are becoming increasingly popular across the African continent. Governments are investing in diverse digital programmes to enable the capture of biometric information of their citizens for various purposes.

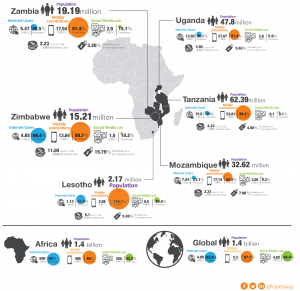

A new report by the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) documents the emerging and current trends in biometric data collection and processing in Africa. It focuses on the deployment of national biometric technology-based programmes in 16 African countries, namely Angola, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Mozambique, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Togo, Tunisia, Uganda, and Zambia.

The report published today is the ninth consecutive one issued by CIPESA since 2014 under the State of Internet Freedom in Africa series. It was released at the Forum on Internet Freedom in Africa (FIFAfrica), which is taking place in Lusaka, Zambia.

The biometric data collection programmes reviewed by the report include those related to civil registrations, such as the issuance of National Identity cards, biometric voter registration and identification programmes, government-led CCTV programmes with facial recognition capabilities, national ePassport initiatives, refugees’ registration, and mandatory biometric SIM card registration.

The report highlights the key trends, potential risks, challenges and gaps relating to biometric data collection projects in the continent. These include limited public engagement and awareness campaigns; inadequate legal frameworks that heighten risks to privacy; exclusion from accessing essential services; enhanced surveillance, profiling and targeting; conflicting interests and the wide powers of third parties; and limited capacity and training.

Consequently, the study notes that these biometric programmes are being implemented in countries with poor digital rights records, declining democracy and rising digital authoritarianism, which casts doubt on the integrity of biometric data collection programmes and the resultant databases. Thus, viewed collectively, the developments, trends and risks outlined in the report heighten concern over the growing threats to the right to privacy of personal data and potential violations of digital rights on the continent.

Finally, the report presents recommendations to various stakeholders including the government, civil society, the media, the private sector and academia, which, if implemented, will go a long way in addressing data protection and privacy gaps, risks and challenges in the study countries.

The key recommendations include a call to:

- Governments to implement the laws and policy frameworks on identity systems and data protection and privacy while paying keen attention to compliance with regionally and internationally recognised principles and minimum standards on data protection and privacy for biometric data collection and require the adoption of human rights-based approaches.

- Countries without data protection and privacy laws such as Liberia, Mozambique, Sierra Leone and Tanzania should expedite the process of enacting appropriate data protection laws so as to guarantee the data protection and privacy rights of their citizens.

- Governments to ratify the AU Convention on Cyber Security and Personal Data Protection (Malabo Convention) to ensure government commitment to regional data protection and privacy as a means to hold them accountable.

- Governments to establish independent and robust oversight data protection bodies to regulate data and privacy protection including biometric data.

- Civil society to engage in advocacy and lobby governments to develop, implement and enforce privacy and data protection policies, laws and institutional frameworks that are in compliance with regional and international minimum human rights standards.

- Civil society to monitor, document and report on the risks, threats, abuses and violations of privacy and human rights associated with biometric data collection programmes, and propose effective solutions to safeguard rights in line with international human rights standards.

- The media to progressively document and report on initiatives such as advocacy by civil society and other stakeholders to keep track of developments.

- The media to conduct investigative journalism to identify and expose privacy violations arising from the implementation of biometric data collection programmes.

- The private sector to take deliberate efforts to ensure that all their respective biometric data collection programmes and systems are developed implemented and managed in compliance with best practices prescribed by the national, regional and international human rights standards and practices on privacy and data protection, including the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

- The private sector to ensure that they progressively adopt and develop comprehensive internal privacy policies to guide the collection, storing and processing of personal data.

- The private sector to take deliberate efforts aimed at involving data subjects in the control and management of their personal data by providing timely information on external requests for information.

- Academia to conduct evidence-based research on data protection and privacy including biometrics, highlighting the challenges, risks, benefits and trends in biometric data collection programmes.

The full State of Internet Freedom in Africa 2022 Report can be accessed here.