The increasing use of the Internet worldwide has continued to see governments put caveats on its openness and the range of freedoms users enjoy online. According to the 2013 Freedom on the Net report, in the period May 2012–April 2013, the global number of censored websites has increased, while internet users in various countries have been arrested, tortured, and killed over the information they posted online.

In Sub Saharan Africa, Freedom House found that both physical and technical mechanisms of filtering, monitoring or otherwise obstructing free speech online have been employed by states concerned with the power of internet-based technologies.

“All 10 of the African countries examined in this report have stepped up their online monitoring efforts in the past year, either by obtaining new technical capabilities or by expanding the government’s legal authority,” says the report which was published by Freedom House on October 3, 2013. Last year, Ethiopia was the only country in the region found to implement nationwide internet filtering.

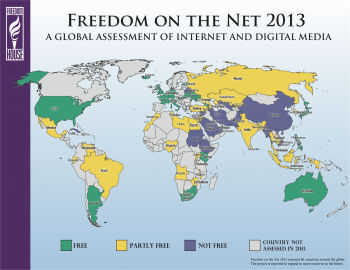

In its study, Freedom House covered developments in internet freedom in 60 countries around the world. Based on an examination of obstacles to access, limits to content, and violation of user rights on the internet, countries were scored as ‘Free’, ‘Partly Free’ or ‘Not Free’.

Table 1: Summary of Global Freedom on the Net Rankings (Source: by author based on Freedom on the Net 2013 report)

| Continent | Free | Not Free | Partly Free | Total |

| Asia | 2 | 8 | 4 | 14 |

| Eurasia | 3 | 5 | 2 | 10 |

| Australia, EU, Iceland and the United States | 9 | 9 | ||

| Latin America | 1 | 4 | 1 | 6 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 5 | 6 | 11 | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 2 | 6 | 2 | 10 |

| Total | 17 | 28 | 15 | 60 |

Free

South Africa and Kenya were the two countries reported as Free. In Kenya, mention was made of the communications regulatory authority issuing guidelines to internet service providers not to allow services to be used to spread hate speech. Service providers were also reportedly required to install internet traffic monitoring equipment.

In South Africa, the proposed Protection of State Information bill which criminalises reporting on classified state information and accessing leaked information online would violate user rights if passed into law. Another legislation, the General Intelligence Laws Amendment 2013, which gives authorities the power to intercept bulk communications known as “foreign signals intelligence” was passed in July 2013. The partially state-owned Telkom network was also said to have installed servers to harvest data and user information. The extent to which this spyware has been deployed in the country was unknown.

Partly Free

Freedom house ranked Malawi, Nigeria, Angola, Uganda, Rwanda and Zimbabwe as ‘Partly Free’. A draft Interception of Communications law in Nigeria was criticised for potentially infringing on user’s right to privacy. There were also reports that the Nigerian government had awarded a contract to an Israeli based company to monitor internet communications. A privately owned ISP was said to have installed surveillance malware. It is unclear if the installation was at the bidding of the state.

Suspicions of online government surveillance in Uganda increased in part due to officials publically expressing “the need” for policing Internet mediums. A new communications law, the Uganda Communications Act, passed in September 2012 created a regulatory authority with sweeping powers to oversee electronic, print and broadcast media. The body’s independence has been called into question. As a sim card (including mobile internet) registration exercises drew to a close, there were privacy concerns due to the country’s lack of data protection legislation. The country already has lawful interception of communications regulations.

There were no reports of internet content being blocked or filtered in Zimbabwe. However, ruling party officials were said to have publicly expressed the desire to increase control over ICTs, particularly in the lead-up to the July 2013 general elections. Zimbabwe was also said to be seeking foreign support for surveillance in Iran. “Personnel from the Zimbabwean armed forces and the Central Intelligence Organisation have been undergoing intensive cyber training in technological warfare techniques, counter-intelligence and methods of suppressing popular revolts among others, every six months,” says the report.

Egypt was also reported to be seeking surveillance assistance from Iran. Activists and social media users were also targeted by security forces during protests either through abductions, killings or prosecution.

In Libya, surveillance equipment from the Muammar Gaddafi regime remained in operation.

Despite being reported as a ”country at risk” in 2013 owing to its “strict” controls over traditional media which were feared may extend to digital media, improvements were reported in Rwanda. An amended media law expanded the rights of journalists and recognised freedom for online communications.

Meanwhile, Angola’s State Security Services, with assistance from Germany, were planning to implement an electronic monitoring system to track digital communications.

Not Free

The Sudanese government was accused of surveillance particularly during protests. In addition to harassment and arrest of journalists during and following the protests, intelligence services are said to have “ramped up” efforts to censor antigovernment content, target cyber-dissidents, and manipulate online information.

In September 2012, Ethiopia “toughened” restrictions on electronic communications by passing the Telecom Fraud Offence Proclamation law. The government was also allegedly increasing its technical capacity to filter, block and monitor the internet with assistance from the Chinese authorities and the use of Finfisher – a commercial spyware software.

Globally, Iceland and Estonia were ranked the freest while China, Cuba and Iran were said to be the “most repressive countries” in terms of internet freedom.

Under the OpenNetAfrica initiative, CIPESA researches into internet freedoms in various African countries. To learn more, to share an idea or report a violation, write to programmes @cipesa.org.