Nouveau Rapport |

Au cours des quatre dernières années, pas moins 22 gouvernements africains ont ordonné des coupures du réseau Internet. Depuis le début de l’année 2019, six pays africains dont l’Algérie, la République Démocratique du Congo (RDC), le Tchad, le Gabon, le Soudan et le Zimbabwe ont déjà connu des coupures d’Internet.

Un nouveau rapport produit par le CIPESA (The Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa) intitulé «Dictateurs et restrictions : cinq dimensions des coupures d’Internet en Afrique» souligne cependant que ces coupures d’Internet sont exclusivement opérées par les Etats les plus despotiques d’Afrique.

Selon ce rapport, 77% des pays où les coupures d’Internet ont été opérées au cours des cinq dernières années sont classés comme autoritaires sur l’indice de démocratie produit par le service de renseignement économique de l’Economist (Economist Intelligence Unit). Hormis ceux-là, tous les autres pays africains qui ont procédé aux coupures de services de communications sont classés dans la catégorie des régimes hybrides, ce qui signifie qu’ils ont certains éléments de démocratie combinés à de fortes doses d’autoritarisme.

Selon ce rapport, 77% des pays où les coupures d’Internet ont été opérées au cours des cinq dernières années sont classés comme autoritaires sur l’indice de démocratie produit par le service de renseignement économique de l’Economist (Economist Intelligence Unit). Hormis ceux-là, tous les autres pays africains qui ont procédé aux coupures de services de communications sont classés dans la catégorie des régimes hybrides, ce qui signifie qu’ils ont certains éléments de démocratie combinés à de fortes doses d’autoritarisme.

Les régimes autoritaires qui ont ordonné des coupures du réseau sont l’Algérie, le Burundi, la République Centrafricaine (RCA), le Cameroun, le Tchad, la RDC, le Congo (Brazzaville), l’Egypte, la Guinée équatoriale, le Gabon, l’Ethiopie, la Libye, la Mauritanie, le Niger, le Togo, le Soudan, et le Zimbabwe. Les régimes hybrides qui ont procédé à des coupures d’Internet comprennent la Gambie, le Mali, le Maroc, la Sierra Léone et l’Ouganda.

Quant aux pays classés comme autoritaires mais qui n’ont pas effectué de telles coupures, le rapport indique qu’il est probable que «l’Etat autoritaire soit si brutal et terrifiant que la société civile ou tout mouvement d’opposition ou de protestation – en ligne et hors ligne- soit étouffé dans l’œuf » ou alors que «les mesures de surveillance d’Internet en place rendent toute coupure inutile». Ces pays comprennent Djibouti, l’Erythrée et le Rwanda.

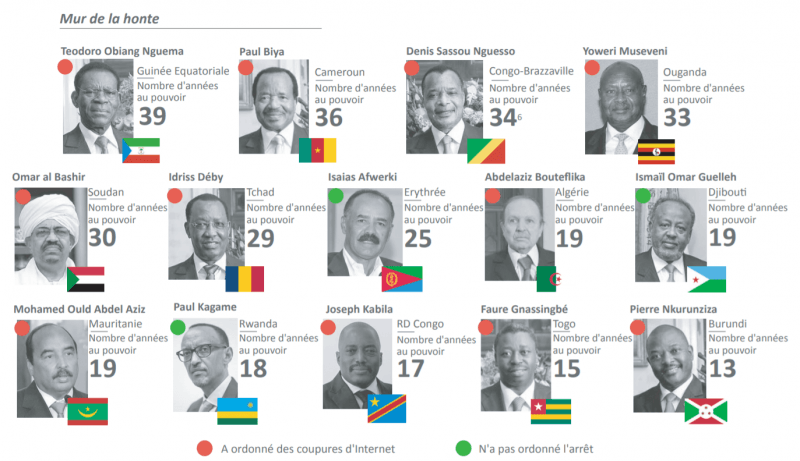

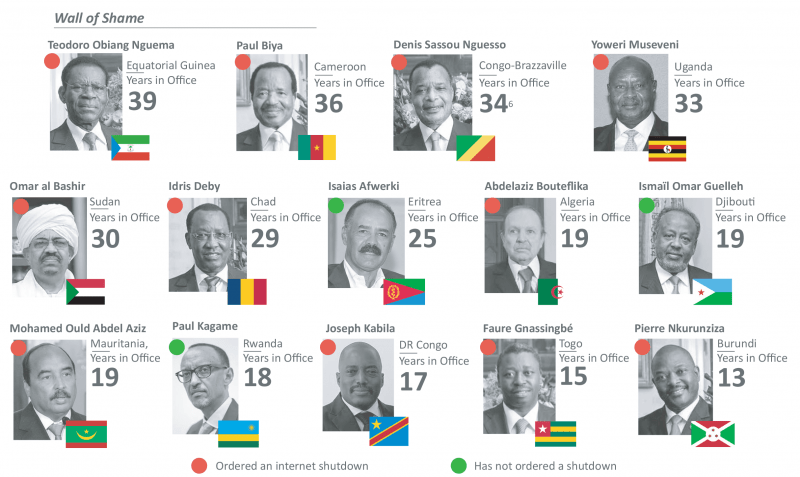

Le rapport note également que les pays dont les dirigeants sont au pouvoir depuis plusieurs années sont plus enclins à ordonner des coupures d’Internet. En janvier 2019, 79% des 14 dirigeants africains qui avaient été au pouvoir depuis 13 ans ou plus avaient ordonné des coupures, principalement pendant les périodes électorales et les protestations publiques contre des politiques gouvernementales.

Il s’agit notamment de Teodoro Obiang Nguema en Guinée équatoriale (39 ans); de Paul Biya au Cameroun (36); de Denis Sassou Nguesso au Congo Brazaville (34); de Yoweri Museveni en Ouganda (33); d’Omar El Bashir au Soudan (30); d’Idriss Déby au Tchad (29); d’Abdelaziz Bouteflika en Algérie (19); de Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz en Mauritanie (19); de Joseph Kabila en RDC (17); de Faure Gnassingbé au Togo (15); et de Pierre Nkurunziza au Burundi (13).

Selon ce rapport, l’année 2019 pourrait connaitre un nombre record de coupures du réseau, car au moins 20 Etats africains tiendront diverses formes d’élections, qu’elles soient locales, législatives, générales ou présidentielles.

Au fil des ans, de nombreuses perturbations du réseau se sont généralement produites dans les pays africains autocratiques autour de périodes électorales, et parmi les Etats qui ont prévu la tenue d’élections durant cette année, certains avaient déjà effectué diverses formes de coupures au cours de périodes électorales précédentes (comme la Guinée équatoriale), de manifestations publiques (Cameroun, Togo) ou à l’occasion d’examens scolaires nationaux (Algérie, Ethiopie).

Autres faits saillants du rapport «Dictateurs et restrictions : cinq dimensions des coupures d’Internet en Afrique» :

Le rapport note que les gouvernements qui ordonnent des coupures et les fournisseurs de services Internet (FSI) qui les mettent en œuvre, assument de plus en plus ouvertement ces actions. Les gouvernements se justifient en disant que les technologies numériques sont de plus en plus utilisées pour diffuser de fausses informations, propager des discours de haine et, prétendument, pour attiser le désordre public et compromettre la sécurité nationale.

De leur côté, de plus en plus de FSIs et d’opérateurs de plateformes de communication rendent publiques leurs réponses aux injonctions de coupure, aux requêtes reçues pour fournir des données personnelles des utilisateurs et aux demandes d’interception émanant des gouvernements grâce aux rapports de transparence. Une telle évolution pourrait conduire à une banalisation des coupures. Comme conséquence, un nombre croissant de gouvernements n’auraient plus honte d’assumer ouvertement les ordres de coupure. Des éléments positifs sont à noter cependant, dans la mesure où cela pourrait servir de base pour l’ouverture d’un procès ou faire avancer le plaidoyer.

Le rapport réaffirme que les coupures d’Internet, même de courte durée, affectent de nombreux pans de l’économie nationale et que leurs impacts persistent bien au-delà des périodes durant lesquelles l’accès a été perturbé. «Même si seuls cinq des pays qui ont déjà coupé l’accès à Internet et qui tiendront des élections refont ce genre d’action durant l’année en cours, notamment la limitation d’accès aux applications telles que Twitter, Facebook et WhatsApp au niveau national pendant cinq jours chacun, le rapport estime que les pertes économiques s’élèveraient à plus de 65,6 millions de dollars américains».

En outre, le rapport note que certains pays qui coupent l’accès à Internet ont des taux d’utilisation d’Internet les plus bas, et des coûts de paquets de données les plus élevés d’Afrique. La logique pourrait suggérer que les pays à faible consommation d’Internet soient les moins enclins à couper l’accès à Internet, du fait que la population en ligne soit trop insignifiante pour menacer «l’ordre public» ou «la sécurité nationale», ou même constituer une entrave sérieuse contre le pouvoir en place. Paradoxalement, le rapport trouve que les gouvernements africains les moins démocratiques, indépendamment du nombre de leurs citoyens qui utilisent internet, craignent la capacité de cet outil à renforcer la participation citoyenne et le franc-parler des citoyens ordinaires face au pouvoir.

Ce rapport peut être téléchargé sur CIPESA.