Who is Dr. Abdul Busuulwa?

I am a Ugandan male with a visual impairment. I come from a humble family where resources were severely limited. Nevertheless, I managed to jump all the hurdles of growing up, and now I have a wife and four children.

With over 25 years of working experience, my career has been shaped around social development, training NGOs, conducting research, engaging in human rights advocacy, and promoting accessible ICTs for persons with disabilities. My career started with a short stint in journalism (freelance reporting) in the late 1990s. I transitioned to disability inclusion and capacity building, holding two positions at the Uganda National Association of the Blind (UNAB) and the National Union of Disabled Persons of Uganda (NUDIPU) between 2000 and 2008. Currently, I am a lecturer at Kyambogo University in the Department of Community and Disability Studies, where I teach several courses, supervise and coordinate research, and train future professionals in Community Development and Social Justice, Community-Based Rehabilitation (CBR), disability studies, and inclusive development. Before my current role, I served as the Executive Director of CBR Africa Network (CAN), a regional organisation dedicated to networking and sharing information on community-based rehabilitation, disability inclusion, and advocacy across the African continent, from 2017 to 2020.

My motivation to become a disability, digital rights, and inclusion advocate in Africa stemmed from the challenges of accessing written information. As a Braille user from primary to tertiary education, I always got limited support in reading printed materials, although resilience and determination enabled me to succeed academically. Very often, I was unable to do class assignments satisfactorily just because of not reading as widely as my educational contemporaries who were endowed with sight. Even when I tried, sighted readers were often less than willing to provide me with adequate support.

The realisation that others were also struggling with the same challenge motivated me to take a six-week certificate course in computer literacy for the blind in 2001, after which I sought to train many of my kind in the use of computers and the Internet so they could easily obtain as much information in digital form as they wished. On a personal note, starting to access documents in soft copy was the real game-changer in my pursuit of a Master’s in Management Studies at Uganda Management Institute and a PhD in Accessible ICTs for People with Visual Disabilities from the University of Twente in the Netherlands. As I mentioned earlier, I struggled with large volumes of notes in Braille notes while pursuing a Bachelor of Arts in Mass Communication from Makerere University and a Postgraduate Diploma in Community-Based Rehabilitation from the Institute of Teacher Education, Kyambogo (now part of Kyambogo University). This was no longer the case after accessing online repositories of articles and so on!

When the government enacted the Access to Information Act of 2005, I ensured that I participated in the process. I submitted my views on access to information for persons with disabilities to the parliamentary committee that was collecting public views.

Two developments have been crucial in the progress toward expanding digital rights and including persons with disabilities in Africa. First was the adoption of the MarrakeshTreaty in 2013, an international agreement on the rights of persons who are blind, have low vision, or have a print disability to access published works. The second was the enactment of the Protocolto the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2018 by the African Union Assembly, which has several articles (especially Article 2 and Article 19) that recognise digital rights for persons with disabilities in Africa.

One initiative I would like to mention is the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. This initiative addresses at least five Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that have direct and/or implicit references to disability inclusion. Furthermore, many African countries have signed and ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), a commendable step towards the realisation and protection of various rights of persons with disabilities. Articles 9 and 21 are specifically related to digital rights; however, Articles 2, 5, 26, and 32 are also highly relevant in this context.

The ever-changing technology landscape is a direct threat to the realisation of digital rights and disability inclusion in Africa. It is worth noting that Africa is not a major manufacturer of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) products, such as computers, smartphones, and other Internet accessories; therefore, enabling their accessibility for persons with disabilities will always remain a retrospective rather than a proactive approach.

Additionally, the two other major challenges to digital rights for persons with disabilities include the high cost of obtaining Assistive Technology (such as screen readers, screen magnifiers, captioning software, alternative keyboards, and automatic speech-to-text translation software) and the emergence of Artificial Intelligence. Very often, persons with disabilities are unemployed and therefore lack the means to procure expensive Assistive Technology they need for effective use of mainstream ICTs. On the side of Artificial Intelligence, although this may increase the precision of Assistive Technology in task completion, some systems where this is embedded may run the risk of perpetuating and replicating discrimination that persons with disabilities are already experiencing in education, employment, and healthcare. For example, Artificial Intelligence (AI) models that cannot take into account the slowness associated with some disabilities in the completion of an input task may fail a person with that disability to ever fill an online form fully and correctly; hence putting them at a disadvantage when trying to apply for a job, medical insurance, or anything else important in their life.

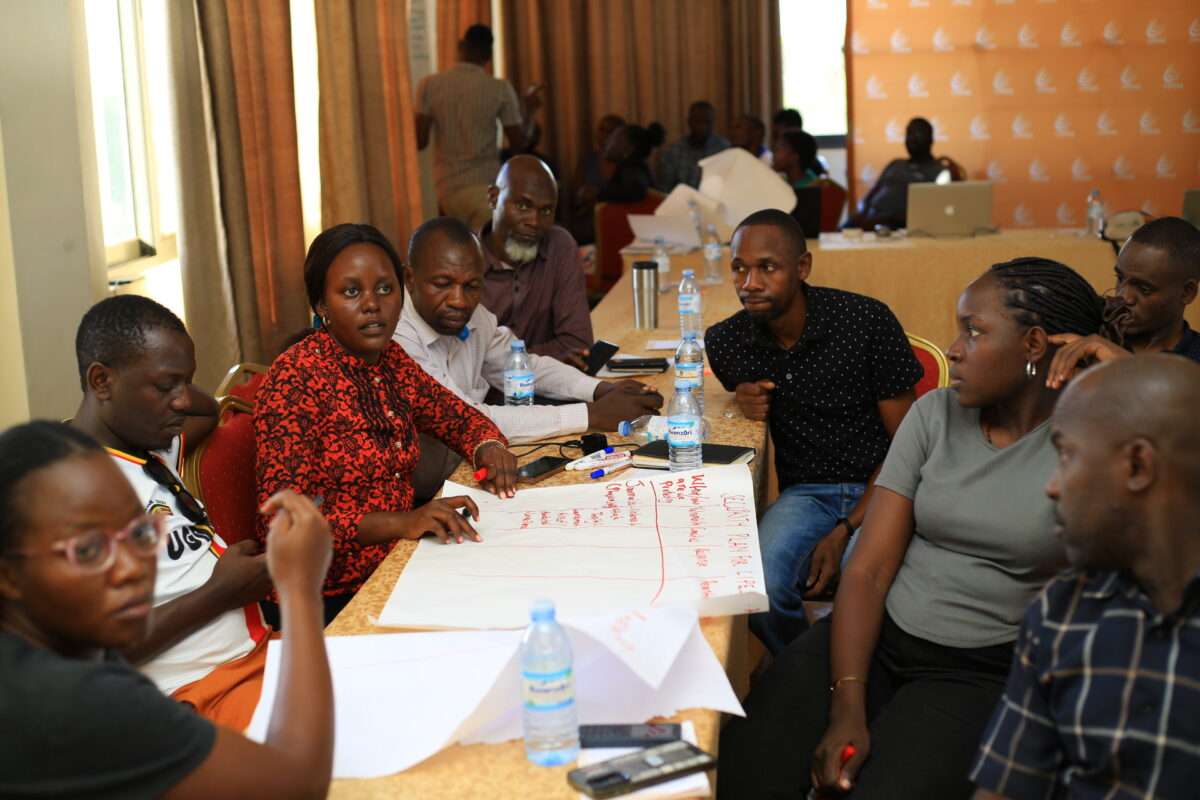

We can build trust, promote partnerships, and enhance regional collaboration among different African stakeholders in the disability rights movement (including governments, inter-governmental bodies, civil society, industry, media, and academia) by simply creating awareness about disability and persons with disabilities. There are several myths and misconceptions about disability and persons with disabilities that require deconstructing and dispelling. For example, some people still believe that disability is a burden to society; hence, persons with disabilities should be isolated and made to live in their own designated parts and should allow the community to get on without them. While others think that persons with disabilities are less intelligent, less able, or less competent in their work. You cannot, therefore, expect such individuals to give jobs to qualified persons with disabilities, either in the public or private sectors of the economy. Many others believe that disability is contagious. These kinds of myths and attitudes hinder disability inclusion efforts, and they have had far-reaching consequences for the realisation of disability rights in Africa. Negative attitudes have always stood in the way of the financial contributions that African governments can make towards dismantling barriers to disability inclusion, such as the provision of Reasonable Accommodations and ensuring accessibility in public transport, education, information, and the physical environment for all, including persons with disabilities.

Disability is a cross-cutting issue. Therefore, the only way to ensure that persons with disabilities and other marginalised communities (women, youth, and older persons) are included in efforts to promote digital rights and inclusion in Africa is to take deliberate efforts to include persons with disabilities in the structures, systems, and processes of other marginalised communities. That way, all efforts to promote digital rights will automatically include issues related to disability. As an academic, I would like to humbly appeal to academic institutions to introduce disability studies course units across all their educational programs to raise awareness about disabilities.