By Ashnah Kalemera |

With many funders shifting their funding priorities about human rights, governance and livelihood issues, African Civil Society Organisations (CSOs), human rights defenders and activists have been severely impacted. As a result, critical programming on civic participation, tech accountability, digital rights and digital inclusion, which was scoring wins in the face of growing authoritarianism on the continent, has been crippled.

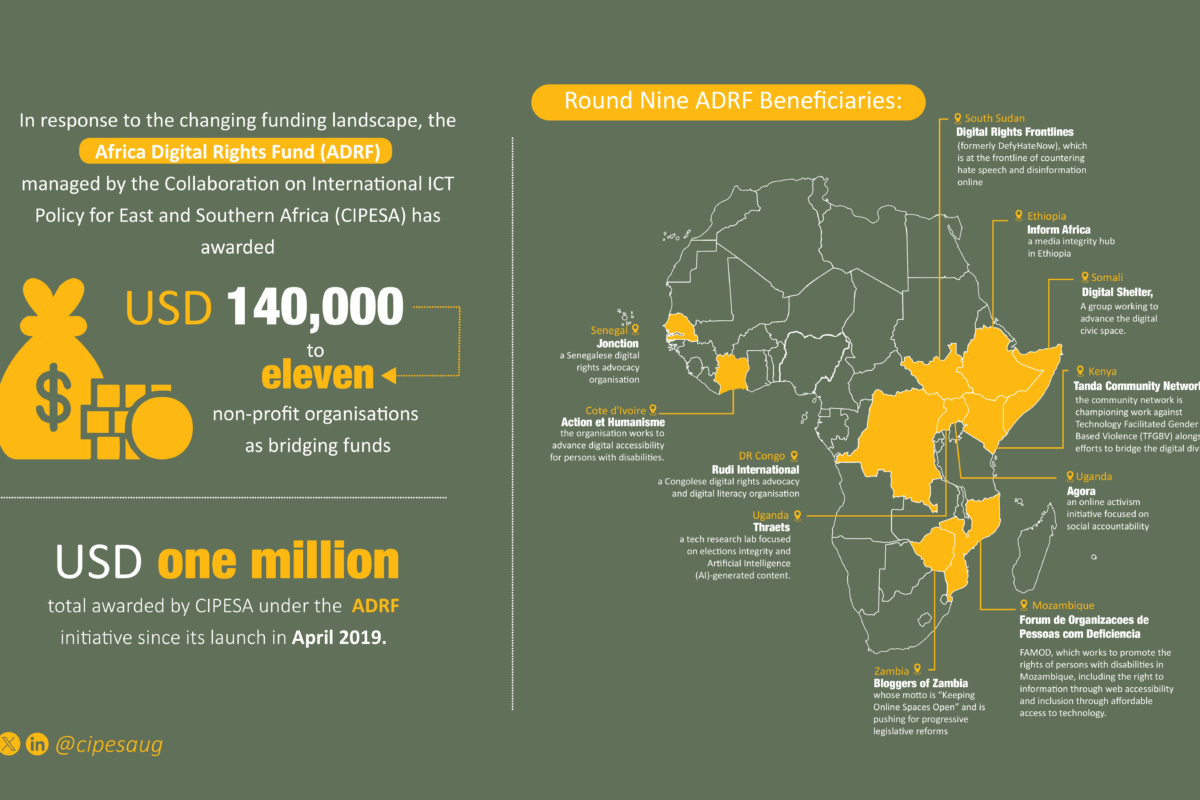

In response to this changing funding landscape, the Africa Digital Rights Fund (ADRF) managed by the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) has awarded USD 140,000 to eleven non-profit organisations as bridging funds. The discretionary awards are aimed at bridging the gap in operations and programming faced by CIPESA’s past and present partners and subgrantees. The funds bring to USD one million the total awarded by CIPESA under the ADRF initiative since its launch in April 2019.

According to CIPESA’s Executive Director, Dr. Wairagala Wakabi, “anchor institutions such as CIPESA have lost funding and that means many crucial but smaller actors across the continent have equally been affected”. Nonetheless, CIPESA is committed to “defending digital democracy amidst the steady democratic regression we are witnessing, and the cruciality of funding organisations that are battling rising authoritarianism cannot be overemphasised,” said Wakabi.

The recipient organisations work on various digital democracy issues in 10 countries – Cote d’Ivorie, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DR Congo), Ethiopia, Kenya, Mozambique, Senegal, Somalia, South Sudan, Uganda and Zambia. These organisations work on catalytic issues in difficult contexts and have established track records. The selection of beneficiaries was guided by a survey on the impact of funding termination by the United States (US) government.

Round Nine ADRF Beneficiaries:

- Action et Humanisme – based in Cote d’Ivoire, the organisation works to advance digital accessibility for persons with disabilities.

- Agora, an online activism initiative focused on social accountability in Uganda.

- Bloggers of Zambia, whose motto is “Keeping Online Spaces Open” and is pushing for progressive legislative reforms in Zambia.

- Digital Rights Frontlines (formerly DefyHateNow), which is at the frontline of countering hate speech and disinformation online in South Sudan.

- Digital Shelter, a Somali group working to advance the digital civic space.

- Forum de Organizacoes de Pessoas com Deficiencia – FAMOD, which works to promote the rights of persons with disabilities in Mozambique, including the right to information through web accessibility and inclusion through affordable access to technology.

- Inform Africa, a media integrity hub in Ethiopia.

- Jonction, a Senegalese digital rights advocacy organisation.

- Thraets, a tech research lab focused on elections integrity and Artificial Intelligence (AI)-generated content.

- Rudi International, a Congolese digital rights advocacy and digital literacy organisation.

- Tanda Community Network, based in Kibera, Nairobi, Kenya, the community network is championing work against Technology Facilitated Gender Based Violence (TFGBV) alongside efforts to bridge the digital divide.

The survey revealed that following the suspension and eventual termination of U.S. funding, many organisations had reduced the scope of their activities, scaled back staff salaries and benefits, and in a number of cases laid off staff. Over 90% of the organisations surveyed were uncertain about their ability to maintain operations beyond two months. Only one of the surveyed organisations said it would remain fully operational if it did not receive additional funding.

A staggering 92% of respondents had reduced programming scope and one in three respondent organisations reported that they had slashed staff. For one recipient, over 60% of the team was “not able to continue working in any capacity going forward”. The percentage of US funding was between 20% and 60% of the annual budgets of the organisations surveyed.

Even in the face of a grim funding future, civil society organisations that face harassment and operate in volatile political environments remain resilient. As the head of one of the grant beneficiary organisations stated: “Unfortunately, we do not have the luxury to cease activities”. The same unwavering commitment to continue operations was demonstrated by the DR Congo-based recipient whose digital literacy training centre was robbed during the January 2025 rebel attacks in Goma.

The ADRF provides financial support to organisations and networks to overcome barriers to accessing funding and building a stronger movement of digital and human rights advocates in Africa. The Fund has also built the capacity of initiatives in advocacy, public communication, research and data-for-advocacy. Supported initiatives commend the ADRF as a unique funding initiative that has broken ranks with traditional funders’ structure. See previous ADRF recipients here.

The discretionary round of the ADRF was supported by funding from the Skoll Foundation, the Wellspring Philanthropic Fund and the Ford Foundation. Other supporters of the ADRF in the past include the Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE), the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida), the German Society for International Cooperation Agency (GIZ), the Omidyar Network, the Hewlett Foundation, the Open Society Foundations and New Venture Fund (NVF).

Another key take away from these two sessions was the need to empower women and girls with information about their rights through access to the internet so they can recognise when those rights are being threatened or violated by another person. Often, women and girls are socialised and conditioned to think that they cannot make decisions without the approval of their male relations because from time in memorial, the power lies with men and women are constantly subjected to finding ways of not upsetting this hold on power and in effect remaining silent in the face of violence.

Another key take away from these two sessions was the need to empower women and girls with information about their rights through access to the internet so they can recognise when those rights are being threatened or violated by another person. Often, women and girls are socialised and conditioned to think that they cannot make decisions without the approval of their male relations because from time in memorial, the power lies with men and women are constantly subjected to finding ways of not upsetting this hold on power and in effect remaining silent in the face of violence.