By CIPESA Writer |

Digital technologies are changing how African businesses trade and connect across borders. However, digital trade on the continent remains hugely constrained, including by regulatory fragmentation, infrastructure gaps, and bureaucratic hurdles. How then should African countries leverage the growing digitalisation and emerging technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) to boost their digital economies?

According to the World Trade Organization (WTO), in 2024, Africa’s exports of digitally delivered services (DDS) were valued at USD 41.3 billion, representing just one percent of global exports. Nonetheless, the continent’s prospects are promising. The WTO and the World Bank project that greater use of digital technologies could boost Africa’s digital services exports by USD 74 billion between 2023 and 2040, doubling Africa’s share of global exports.

Evidently, if African countries do not address existing barriers and take decisive action, the continent risks becoming an even more marginal player in the global digital trade ecosystem. How to bridge the barriers and leverage data and AI to shape digital trade and Africa’s economic future was at the centre of discussions at the African Economic Research Consortium (AERC) Summit 2025, held in Nairobi, Kenya, last December.

A panel on digital trade and the governance of digital and AI economies, where the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) featured, stressed that, although frameworks such as the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) Digital Trade Protocol are a step in the right direction, they could fail to significantly grow digital trade if member states lack enabling data and AI governance systems and practices.

Today, DDS account for approximately 35% of Africa’s total services export value, and have been rising at a double-digit rate, outpacing growth in other regions globally. However, growth in digital services trade remains uneven, concentrated in a handful of countries, mostly South Africa, Morocco, Ghana, Egypt, and Mauritius. Kenya, Nigeria and Tunisia are also notable players but with lower export values than the leading African countries.

Regional initiatives such as the AfCFTA Digital Trade Protocol can help to expand digital trade beyond domestic markets, including in countries that currently lag. The protocol, which was adopted two years ago, aims to harmonise rules for cross-border digital trade across Africa, including on electronic transactions, data governance, and digital payments. Meanwhile, the African Guidelines on Integrating Data Provisions in Protocols on Digital Trade of 2024, emphasise harmonised data governance as an enabler of secure and inclusive digital trade across Africa.

The African Union Data Policy Framework (AUDPF) similarly provides for interoperable data ecosystems across the continent, that are enabled by harmonised laws that support both innovation and rights protection. The various regional efforts support the dream of a Digital Single Market by 2030, as envisaged by the Africa Digital Transformation Strategy of the African Union.

The Galore of Barriers

The region currently lacks an operational continent‑wide harmonised framework for data protection, e‑commerce regulation, digital taxation, or AI governance. This gap raises compliance costs and presents a barrier to businesses that aim to scale operations across borders. This undermines cross‑border digital trade and data flows. Moreover, lack of regulations for paperless trade, including on electronic invoicing, e-signatures and e-contracts, presents an additional hurdle.

On the other hand, high taxes on goods, services, data, and devices drive up costs for businesses, yet several entrepreneurs struggle to access affordable digital financial services, including for effecting cross-border payments. These challenges are made worse by low internet speeds, unreliable electricity supply, as well as weak understanding of export regulations, data protection, and cybersecurity.

Addressing these barriers would offer entrepreneurs a range of benefits. Businesses can reach new customers beyond national borders without investing much in physical export infrastructure, which can reduce costs and expand their market reach. Also, interoperable digital payments can help to minimise settlement delays and overcome currency conversion hurdles.

Priorities on AI and Data Governance

Projections by a WTO 2025 report show that AI could boost the value of cross-border flows of goods and services by around 40% by 2040, due to productivity gains and lower trade costs. However, Africa’s readiness for AI regulation and uptake, particularly by small and medium enterprises, remains low. The WTO report points to AI’s potential to reduce logistics costs, overcome language barriers, ease regulatory compliance, and boost productivity.

In a March 2025 survey among firms from across the world, the most cited benefits of AI were improved trade efficiency (22%), optimised trade decision-making (14%), expanding the foreign customer base (10%), enhanced supply chain management (9%), and broader import and export product ranges (9% and 8% respectively).

How data and AI are governed is therefore key for the future of Africa’s digital economy. If African countries do not put in place robust and harmonised legislation, they will risk perpetuating patterns of the so-called “AI colonialism” in which African data and users fuel global AI markets yet their economies do not receive proportionate economic benefits. Many African countries are adopting AI in the public and private sectors but lack comprehensive AI-specific laws and governance frameworks and often rely instead on outdated laws that pre-date the current technologies.

The State of Internet Freedom in Africa 2025 report calls for human‑centred AI laws that ensure transparency in algorithms, clear accountability, and effective mechanisms for liability and redress. The report urges governments to strengthen independent AI and data oversight institutions, invest in digital infrastructure and inclusion, expand internet access, and ensure AI tools serve local languages. The report also highlights that Africa’s AI market is projected to grow from USD 4.51 billion in 2025 to USD 16.5 billion by 2030.

Africa thus urgently needs cross-border data governance frameworks that support trusted data flows, reduce fragmented national rules, and establish interoperable standards to boost regional digital trade under initiatives such as AfCFTA and the AUDPF. At the same time, investments in affordable connectivity, local cloud capacity, public digital platforms, and datasets in African languages are essential.

The Role of Civil Society and Think Tanks

The Summit discussion stressed the urgent need for research to inform policy, particularly on cross-border data flows, AI adoption, and ways for Africa to avoid new forms of dependency while getting greater value from its data and digital innovation.

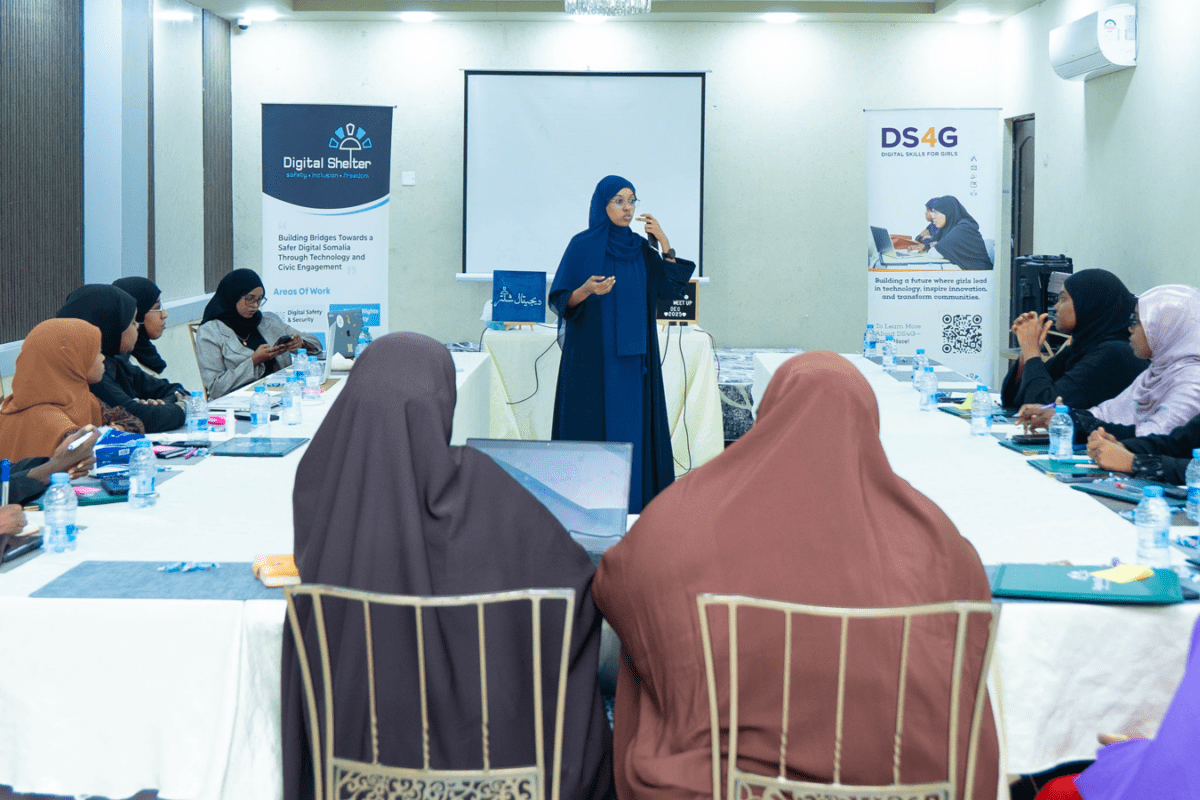

Also essential is civil society engagement in monitoring the implementation of continental digital trade and data initiatives, supporting harmonisation of policies and standards, and building the capacity of policymakers, regulators, and businesses.

Actions to Grow Digital Trade in Africa

- Embrace digital transformation and connectivity by investing in robust networks and backup systems.

- Implement robust cyber security frameworks while ensuring effective cyber leadership and prioritising investments in cyber infrastructure, skilling, awareness.

- Recognise data as a trade enabler by ensuring trade agreements have provisions that prevent unnecessary restrictions on data flows.

- Harmonise data protection standards to reduce compliance costs for businesses and build trust among different stakeholders.

- Adopt and implement Intellectual Property (IP) laws to ensure that local innovators and individuals in the region benefit.

- Build robust digital infrastructure with a focus on Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) and data privacy.

- Assess and address the impact of emerging technologies like artificial intelligence, blockchain and IoT, ensuring they foster innovation and address ethical challenges.

Source: CIPESA – Policy Considerations for Enhancing Digital Trade in East Africa