By Brian Byaruhanga and Morine Amutorine |

As Artificial Intelligence (AI) rapidly transforms Africa’s digital landscape, it is crucial that digital governance and oversight align with ethical principles, human rights, and societal values.

Multi-stakeholder and participatory regulatory sandboxes to test innovative technology and data practices are among the mechanisms to ensure ethical and rights-respecting AI governance. Indeed, the African Union (AU)’s Continental AI Strategy makes the case for participatory sandboxes and how harmonised approaches that embed multistakeholder participation can facilitate cross-border AI innovation while maintaining rights-based safeguards. The AU strategy emphasises fostering cooperation among government, academia, civil society, and the private sector.

As of October 2024, 25 national regulatory sandboxes have been established across 15 African countries, signalling growing interest in this governance mechanism. However, there remain concerns on the extent to which African civil society is involved in contributing towards the development of responsive regulatory sandboxes. Without the meaningful participation of civil society in regulatory sandboxes, AI governance risks becoming a technocratic exercise dominated by government and private actors. This creates blind spots around justice and rights, especially for marginalised communities.

At DataFest25, a data rights event hosted annually by Uganda-based civic-rights organisation Pollicy, the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA), alongside the Datashphere Initiative, hosted a session on how civil society can actively shape and improve AI governance through regulatory sandboxes.

Regulatory sandboxes, designed to safely trial new technologies under controlled conditions, have primarily focused on fintech applications. Yet, when AI systems that determine access to essential services such as healthcare, education, financial services, and civic participation are being deployed without inclusive testing environments, the consequences can be severe.

CIPESA’s 2025 State of Internet Freedom in Africa report reveals that AI policy processes across the continent are “often opaque and dominated by state actors, with limited multistakeholder participation.” This pattern of exclusion contradicts the continent’s vibrant civil society landscape, where various organisations in 29 African countries are actively working on responsible AI issues and frequently outpacing government efforts to protect human rights.

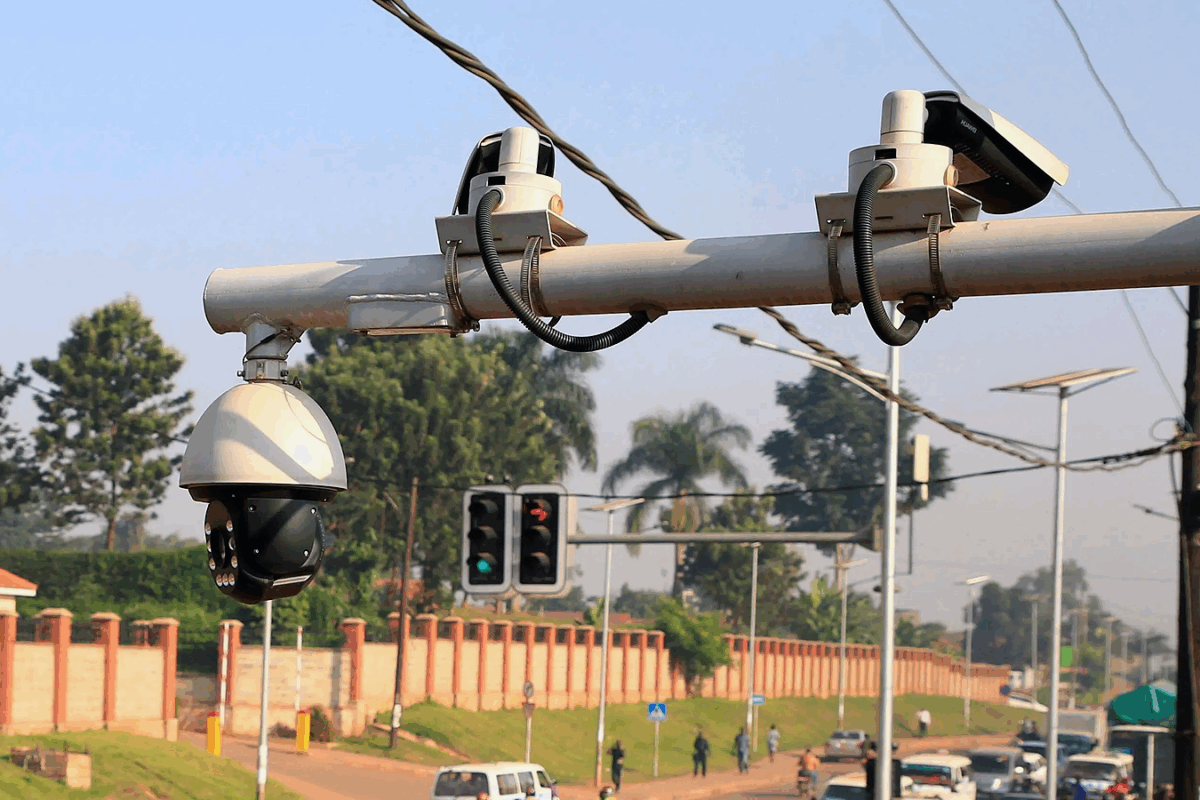

The Global Index on Responsible AI found that civil society organisations (CSOs) in Africa are playing an “outsized role” in advancing responsible AI, often surpassing government efforts. These organisations focus on gender equality, cultural diversity, bias prevention, and public participation, yet they face significant challenges in scaling their work and are frequently sidelined from formal governance processes. The consequences that follow include bias and exclusion, erosion of public trust, surveillance overreach and no recourse mechanisms.

However, when civil society participates meaningfully from the outset, AI governance frameworks can balance innovation with justice. Rwanda serves as a key example in the development of a National AI Policy framework through participatory regulatory processes.

Case Study: Rwanda’s Participatory AI Policy Development

The development of Rwanda’s National AI Policy (2020-2023) offers a compelling model for inclusive governance. The Ministry of ICT and Innovation (MINICT) and Rwanda Utilities Regulatory Agency (RURA), supported by GIZ FAIR Forward and The Future Society, undertook a multi-stakeholder process to develop the policy framework. The process, launched with a collective intelligence workshop in September 2020, brought together government representatives, private sector leaders, academics, and members of civil society to identify and prioritise key AI opportunities, risks, and socio-ethical implications. The Policy has since informed the development of an inclusive, ethical, and innovation-driven AI ecosystem in Rwanda, contributing to sectoral transformation in health and agriculture, over $76.5 million in investment, the establishment of a Responsible AI Office, and the country’s role in shaping pan-African digital policy.

By embedding civil society in the process from the outset, Rwanda ensured that its AI governance framework, which would guide the deployment of AI within the country, was evaluated not just for performance but for justice. This participatory model demonstrates that inclusive AI governance through multi-stakeholder regulatory processes is not just aspirational; it’s achievable.

Rwanda’s success demonstrates the power of participatory AI governance, but it also raises a critical question: if inclusive regulatory processes yield better outcomes for AI-enabled systems, why do they remain so rare across Africa? The answer lies in systemic obstacles that prevent civil society from accessing and influencing sandbox and regulatory processes.

Consequences of Excluding CSOs in AI Regulatory Sandbox Development???

The CIPESA-DataSphere session explored the various obstacles that civil society faces in the AI regulatory sandbox processes in Africa as it sought to establish ways to advance meaningful participation.

The session noted that CSOs are often simply unaware that regulatory sandboxes exist. At the same time, authorities bear responsibility for proactively engaging civil society in such processes. Participants emphasised that civil society should also take proactive measures to demand participation as opposed to passively waiting for an invitation.

The proactive measures by CSOs must move beyond a purely activist or critical role, developing technical expertise and positioning themselves as co-creators rather than external observers.

Several participants highlighted the absence of clear legal frameworks governing sandboxes, particularly in African contexts. Questions emerged: What laws regulate how sandboxes operate? Could civil society organisations establish their own sandboxes to test accountability mechanisms?

Perhaps most critically, there’s no clearly defined role for civil society within existing sandbox structures. While regulators enter sandboxes to provide legal oversight and learn from innovators, and companies bring solutions to test and refine, civil society’s function remains ambiguous with vague structural clarity about their role. This risks civil society being positioned as an optional stakeholder rather than an essential actor in the process.

Case Study: Uganda’s Failures Without Sandbox Testing

Uganda’s recent experiences illustrate what happens when digital technologies are deployed without inclusive regulatory frameworks or sandbox testing. Although not tested in a sandbox—which, according to Datasphere Initiative’s analysis, could have made a difference given sandboxes’ potential as trust-building mechanisms for DPI systems– Uganda’s rollout of Digital ID has been marred by controversy. Concerns include the exclusion of poor and marginalised groups from access to fundamental social rights and public services. As a result, CSOs sued the government in 2022. A 2023 ruling by the Uganda High Court allowed expert civil society intervention in the case on the human rights red flags around the country’s digital ID system, underscoring the necessity of civil society input in technology governance.

Similarly, Uganda’s rushed deployment of its Electronic Payment System (EPS) in June 2025 without participatory testing led to public backlash and suspension within one week. CIPESA’s research on digital public infrastructure notes that such failures could have been avoided through inclusive policy reviews, pre-implementation audits, and transparent examination of algorithmic decision-making processes and vendor contracts.

Uganda’s experience demonstrates the direct consequences of the obstacles outlined above: lack of awareness about the need for testing, failure to shift mindsets about who belongs at the governance table, and absence of legal frameworks mandating civil society participation. The result? Public systems that fail to serve the public, erode trust, and costly reversals that delay progress far more than inclusive design processes would have.

Models of Participatory Sandboxes

Despite the challenges, some African countries are developing promising approaches to inclusive sandbox governance. For example, Kenya’s Central Bank established a fintech sandbox that has evolved to include AI applications in mobile banking and credit scoring. Kenya’s National AI Strategy 2025-2030 explicitly commits to “leveraging regulatory sandboxes to refine AI governance and compliance standards.” The strategy emphasises that as AI matures, Kenya needs “testing and sandboxing, particularly for small and medium-sized platforms for AI development.”

However, Kenya’s AI readiness Index 2023 reveals gaps in collaborative multi-stakeholder partnerships, with “no percentage scoring” recorded for partnership effectiveness in the AI Strategy implementation framework. This suggests that, while Kenya recognises the importance of sandboxes, implementation challenges around meaningful participation remain.

Kenya’s evolving fintech sandbox and the case study from Rwanda above both demonstrate that inclusive AI governance is not only possible but increasingly recognised as essential.

Pathways Forward: Building Truly Inclusive Sandboxes

Session participants explored concrete pathways toward building truly inclusive regulatory sandboxes in Africa. The solutions address each of the barriers identified earlier while building on the successful models already emerging across the continent.

Creating the legal foundation

Sandboxes cannot remain ad hoc experiments. Participants called for legal frameworks that mandate sandboxing for AI systems. These frameworks should explicitly require civil society involvement, establishing participation as a legal right rather than a discretionary favour. Such legislation would provide the structural clarity currently missing—defining not just whether civil society participates, but how and with what authority.

Building capacity and awareness

Effective participation requires preparation. Participants emphasised the need for broader and more informed knowledge about sandboxing processes. This includes developing toolkits and training programmes specifically designed to build civil society organisation capacity on AI governance and technical engagement. Without these resources, even well-intentioned inclusion efforts will fall short.

Institutionalise cross-sector learning.

Rather than treating each sandbox as an isolated initiative, participants proposed institutionalising sandboxes and establishing cross-sector learning hubs. These platforms would bring together regulators, innovators, and civil society organisations to share knowledge, build relationships, and develop a common understanding about sandbox processes. Such hubs could serve as ongoing spaces for dialogue rather than one-off consultations.

Redesigning governance structures

True inclusion means shared power. Participants advocated for multi-stakeholder governance models with genuine shared authority—not advisory roles, but decision-making power. Additionally, sandboxes themselves must be transparent, adequately resourced, and subject to independent audits to ensure accountability to all stakeholders, not just those with technical or regulatory power.

The core issue is not if civil society should engage with regulatory sandboxes, but rather the urgent need to establish the legal, institutional, and capacity frameworks that will guarantee such participation is both meaningful and effective.

Why Civil Society Participation is Practical

Research on regulatory sandboxes demonstrates that participatory design delivers concrete benefits beyond legitimacy. CIPESA’s analysis of digital public infrastructure governance shows that sandboxes incorporating civil society input “make data governance and accountability more clear” through inclusive policy reviews, pre-implementation audits, and transparent examination of financial terms and vendor contracts.

Academic research further argues that sandboxes should move beyond mere risk mitigation to “enable marginalised stakeholders to take part in decision-making and drafting of regulations by directly experiencing the technology.” This transforms regulation from reactive damage control to proactive democratic foresight.

Civil society engagement:

- Surfaces lived experiences regulators often miss.

- Strengthens legitimacy of governance frameworks.

- Pushes for transparency in AI design and data use.

- Ensures frameworks reflect African values and protect vulnerable communities, and

- Enables oversight that prevents exploitative arrangements

While critics often argue that broad participation slows innovation and regulatory responsiveness, evidence suggests otherwise. For example, Kenya’s fintech sandbox incorporated stakeholder feedback through 12-month iterative cycles, which not only accelerated the launch of innovations but also strengthened the country’s standing as Africa’s premier fintech hub.

The cost of exclusion can be seen in Uganda’s EPS system, the public backlash, eroded trust, and potential system failure, ultimately delaying progress far more than inclusive design processes. The window for embedding participatory principles is closing. As Nigeria’s National AI Strategy notes, AI is projected to contribute over $15 trillion to global GDP by 2030. African countries establishing AI sandboxes now without participatory structures risk locking in exclusionary governance models that will be difficult to reform later.

The future of AI in Africa should be tested for justice, not just performance. Participatory regulatory sandboxes offer a pathway to ensure that AI governance reflects African values, protects vulnerable communities, and advances democratic participation in technological decision-making.

Join the conversation! Share your thoughts. Advocate for inclusive sandboxes. The decisions we make today about who participates in AI governance will shape Africa’s digital future for generations.