By Small Media |

Building off the success of our 2016 report ‘Supercharging Human Rights Advocates in the Levant’, the Small Media team is excited to announce our latest project in a whole new region. Making use of the practices we’ve developed in our work across the Middle East, Small Media is setting out to survey the cybersecurity landscape in East Africa. Over the course of this project, we aim assess the state of internet controls in the region, and support the development of a regional community of internet freedom researchers, digital security experts, and human rights defenders.

Over recent years, regional civil society organisations and human rights defenders have been confronted with significant security challenges as internet freedom is threatened across East Africa. The Collaboration on International ICT Policy in East and Southern Africa (CIPESA), one of our local partners for this project, have highlighted various issues involving undue prosecution of Internet users in East Africa in their 2016 State of Internet Freedom in Africa report. In Tanzania this has involved users being targeted and arrested for offenses including ‘insulting the president’ and news sites being shut down. Netizens in Uganda faced blocked social media and mobile money services in the build up to the February 2016 elections, alongside crackdowns on ‘offensive communications’, in the form of bans on social media accounts that criticise the government. Burundian social media users have seen platforms including Viber, Twitter, WhatsApp and Facebook shut down during public protests against government figures. In addition to this, Rwandan citizens face among the world’s worst restrictions on freedom of speech and political activity, including stringent online censorship targeted at those discussing ‘sensitive’ topics.

Freedom House’s 2016 Freedom on the Net report highlights the challenges faced in Rwanda and Uganda, but there are a number of gaps in regional knowledge that we aim to fill. With levels of access to the Internet growing steadily in the region, and some concerning indications of a ramping-up of state efforts to crackdown on internet freedom, it is important that the digital security needs of CSOs and netizens are addressed in an urgent manner.

Thus, focusing on Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and Tanzania, our research seeks to fill the gap that exists by identifying the digital security threats facing CSOs in the East Africa region, recommending a plan of action and then developing the capacity of CSOs to respond to the threats that they face.

Our Project

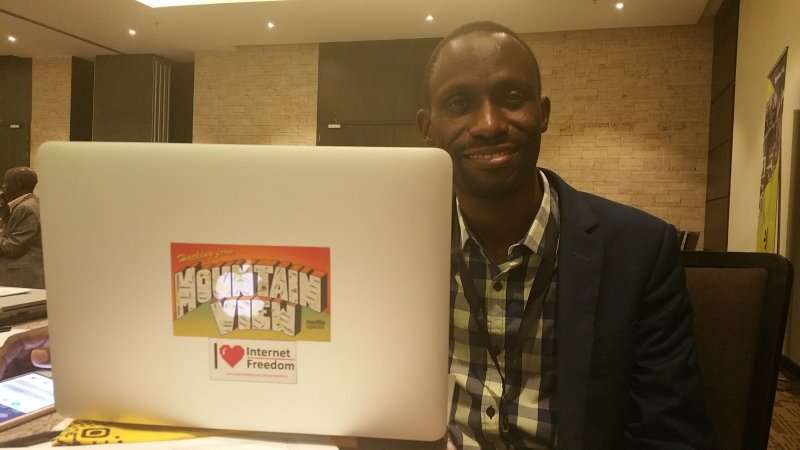

The first phase of this project involved working with two of our local partners, CIPESA and DefendDefenders, to select high-quality workshop participants and trainers, in order to create and train a secure, strong and enthusiastic community of regional, on-the-ground digital security experts and researchers. The training given at the workshop has equipped local actors to engage in comprehensive and long-term digital security research, thereby supporting the future needs of CSOs across the region.

Building on the successful outcome of the workshop, our local researchers – working alongside our regional partners – are now hard at work carrying out the core components of the research project, including:

- Legal and Policy Analysis – to assess the current legislative frameworks that exist within East African states, and to establish what powers governments have to monitor and prohibit online communications.

- Network Measurements – to assess the internet infrastructure in each of the target countries. Our researchers are using OONI Probe and ICLab’s Centinel software to establish the level of censorship taking place, and highlight any network vulnerabilities to state-directed internet shutdowns.

- CSO Cyber Capacity Assessments – interviews are being undertaken with a number of CSOs to identify the most urgent digital security threats they face, and to measure their defences.

With the training workshop completed, Small Media and our local partners are currently working with an enthusiastic team of local researchers to carry out the on-the-ground research components. We’ll be busily compiling our research findings over the next couple of months, but we look forward to presenting you with our findings and recommendations upon the report’s publication in March 2017. Stay tuned!

This article was sourced from the Small Media website.