The Collaboration on International ICT Policy in East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) is seeking an evaluation consultant to establish the achievements, outcome and challenges registered by the ICT4Democracy in East Africa Network during the period June 2016 to December 2018. The evaluation will assess the appropriateness, effectiveness and outcomes of the network in relation to the program objectives

Closing date for applications: 17:00 hours East African Time (EAT) on Friday December 7, 2018

Further details on the scope, eligibility and how to apply are available here.

Amplifying Community Rights Through Social Media in Kenya

Tweet

By Ashnah Kalemera |

Human rights violations incidents are on the rise in Kenya with extrajudicial killings and police brutality among the cases reported recently. Social media has enabled quick reporting of such cases while also creating increased awareness of the reported incidents. Through a mix of Twitter, radio and physical engagements, the Kenya Human Rights Commission (KHRC) is improving its effectiveness in promoting human rights and documenting violations in the lead up to the 2017 national elections.

The commission is seeing success in mobilising citizens for protests and marches, as well as getting stakeholders to participate in debates related to human rights. Through quarterly Twitter chats, the KHRC is popularising various human rights issues and bringing to the fore struggles faced by communities that have little online presence and who have limited avenues for participating in community affairs.

A Twitter chat hosted in September 2016 to promote dialogue on governance and anti-corruption drew panelists from the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA-Kenya), Transparency International Kenya, International Commission of Jurists (ICJ)-Kenya, Society for International Development and Kenya Association of Manufacture (KAM).

Another chat on insecurity (under the hashtag #InSecurityKE) hosted in July 2016 explored the causes of social insecurity, challenges faced in addressing it and proposals for over coming those challenges. Panelists included the Kenya National Commission

coming those challenges. Panelists included the Kenya National Commission

on Human Rights, Amnesty International Kenya, Independent Medico-Legal Unit (IMLU) and ICJ-Kenya.

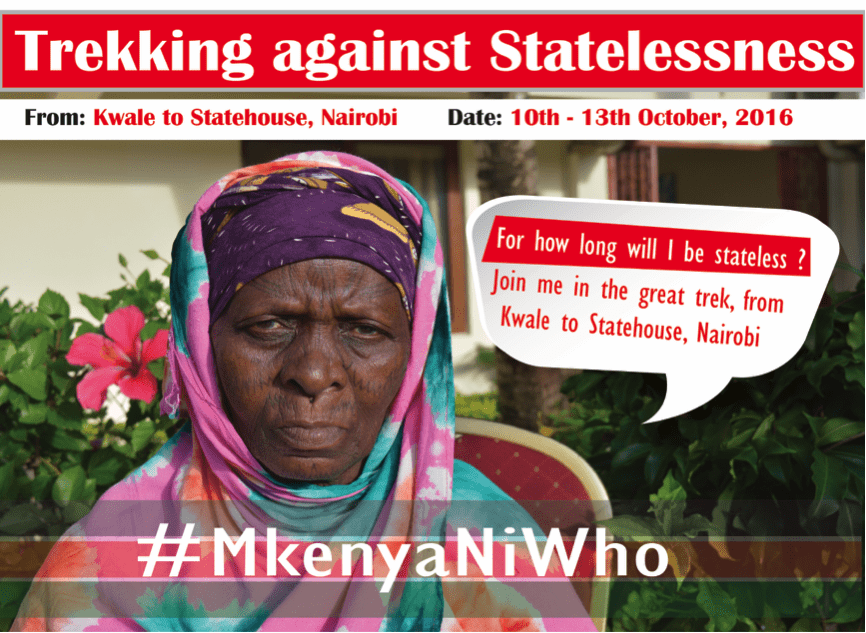

In another drive, the KHRC on October 10-13, 2016 mobilised 300 members of the Makonde community who live along the south eastern coast of Kenya for a walk dubbed “Trek against Statelessness”, from Kwale county to the capital Nairobi. The walk was in protest against the exclusion of the community from attaining formal national recognition and identity documentation. Several members of the Makonde community have lived in Kenya for about half a century after many of them immigrated from Mozambique.

Upon arrival at the State House, President Uhuru Kenya gave audience to the community and promised that all of the members would be registered as citizens. The registration process kicked off on October 24 and ended on November 10, 2016.

In the weeks leading up to the walk, among the channels utilised by the commission to mobilise participants were online platforms, with the hashtag #MKenyaNiWho (“Who is a Kenyan”) used to raise awareness of the Makonde community’s plight. Furthermore, a radio talk show was hosted on Citizen Radio for the Kwale Human Rights Network to discuss issues of registration of the Makonde community as Kenya Citizens.

Earlier in July, citizenship and statelessness, identity and belonging were also discussed at the Samosa Festival in Kenya. Among the key areas of discussions were the difficulties faced by Kenyans of Somali descent when applying for national identity cards and birth certificates in the northern part of the country. The discussion attracted members of parliament and members of communities that are struggling with the issue of citizenship.

Meanwhile, to support its efforts at grassroots level, KHRC has built the capacity of 14 Human Rights Networks (Hurinets) in four regions – Mombasa, Nairobi, Kisumu and Nyeri – to engage on issues of electoral governance and devolution including through social media. The beneficiary Hurinets included Kwale, Mombasa, Kinangop, Taita Taveta, Kakamega, Siaya, Migori, Nairobi, Makueni, Wajir, Nakuru, Nyeri, Kiambu and Isiolo. A total of 103 members of the networks (57% male and 43% female) have benefitted from the training.

The increased capacity of the Hurinets in Kenya to promote discussions on human rights issues in remote and rural areas where the Hurinets are based is expected to contribute to more issues being brought to the attention of local and national government primarily through social media. In 2015, the Midrift Hurinet in Nakuru County started #UwajibikajiMashinani “AccountabilityInRuRalAreas” hashtag campaign to get more citizens to deliberate on issues of accountability in the county. The Kwale Hurinet started #OkoaKwaleInitiative and “SaveKwaleInitiative” hashtag campaigns that asked Kwale county government leaders not to allow petty, personal differences to influence community decisions.

KHRC is a member of the ICT4Democracy in East Africa Network whose work is supported by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) and the Swedish Programme for ICT in Developing Regions (Spider). The network is coordinated by the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA).

See also ICT4Democracy in East Africa Annual Report 2015 and using technology to advance human rights in Kenya.

Using Technology to Advance Human Rights in Kenya

By Catherine Kamatu |

Joseph Kitaka, a resident of Yatta in Machakos County, Kenya, has always had an interest in defending human rights. His community is faced with numerous challenges, including gender-based violence, police brutality and many other human rights violations. Mr. Kitaka had little hope of utilising Information and Communication Technology (ICT) to advance his ambition in bettering his community, until he was elected the chairman of Yatta Paralegal Network, a local Human Rights Network (HURINET).

Today, Yatta, is among 15 HURINETs in Kenya that are being supported by the Kenya Human Rights Commission (KHRC) to strengthen democratisation by widening civil society use of ICT to advance political accountability, freedom of expression and respect for human rights. The initiative is part of the ICT4Democracy in East Africa Network, a regional coalition of civil society organisations coordinated by the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA).

The network maintains various ICT platforms and undertakes activities including research, capacity building, mentoring, advocacy and civic engagement toward strengthening democracy. The network’s partners use digital technologies to hold leaders accountable to citizens, fight corruption, enhance communication and the right to freedom of expression, as well as the right to seek, receive and impart information and respect for human rights.

In Kenya, KHRC maintains an SMS short code and crowd mapping platform which enable citizen reporting of human rights violations, and building a vibrant social movement of citizens who monitor government performance toward a society free of human rights violations.

Through KHRC’s project, 10 HURINETs have received computers, modems, generators and digital cameras to support their work. Mr. Kitaka received a modem, a computer and a digital camera to enable the smooth operations of his network. He asserts that the equipment greatly eased information sharing among the networks and other human rights defenders.

“Three years ago, sharing information was a challenge. It took very long for human rights defenders to share reports, it was also very expensive since we could only access ICT equipment in cyber cafes at a cost. With the equipment given to us by KHRC, everything is moving on well,” he said.

Earlier in 2014, KHRC conducted two community outreaches in the Kibera and Kangemi informal settlements in the capital of Kenya where active audiences of 109 and 138 respectively were trained in the use of ICT platforms for promoting human rights and good governance. These engagements enabled hundreds of ordinary citizens to use web tools (such as SMS, Facebook, HakiReport, HakiZetu) to report on governance processes.

Kenya has high rates of access to digital technology, with mobile access rates at 80% and internet access rates at 57%. However, most citizens do not have the skills to use simple technology tools in pursuance of good governance at a time the Kenyan government is making laws and regulations that limit freedom of expression.

In a bid to enhance the quality of the content generated by the human rights networks, KHRC further trained human rights defenders on communications skills in February 2015. The training focused on news writing, multimedia use, interview skills, social media and use of the KHRC e-library as a research tool.

The training was attended by 15 local human rights workers, who will collectively contribute to the newsletter Mizizi ya Haki (The Roots of Justice), which focuses on activities of human rights networks. “From the skills obtained from the communications training facilitated by KHRC, I have managed to train other human rights defenders on how to file good reports,” added Mr. Kitaka.

The training evaluation indicated an overall change in the knowledge, skills and attitudes of all beneficiaries. Social media and article writing were indicated as the most useful training sessions toward the beneficiaries’ more effective human rights work.

However, further training needs were also identified, including digital security, media laws and multi-media content generation. Participants also identified a need for training in proposal writing and resources mobilisation as well as in paralegal work.

Read the full evaluation report here http://bit.ly/1Pu1w6h

The work of KHRC and the ICT4Democracy Network is supported by Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida).

Is Kenya Putting the Chill on Internet Freedoms?

By Juliet Nanfuka |

The rights of Kenya’s digital citizens are fast shrinking in the face of new restrictive laws and increased arraignment of individuals for expressing online opinions which authorities deem in breach of the law.

The Security Laws (Amendment) Act 2014, assented to by President Uhuru Kenyatta last December, allows blanket admissibility in court of electronic messages and digital material regardless of whether it is not in its original form.

It is feared that retrogressive provisions in this law could be used to put the chill on internet freedoms in East Africa’s most connected country where mobile phone penetration stands at 80% and internet access at 50% of the population.

Part V of the new security law regarding “special operations” has raised particular concerns, as it expands the surveillance capabilities of the Kenyan intelligence and law enforcement agencies without sufficient procedural safeguards.

It gives broad powers to the Director General of the National Intelligence Service to authorise any officer of the Service to monitor communications, “obtain any information, material, record, document or thing” and “to take all necessary action, within the law, to preserve national security.”

In addition, the amendments also contain unclear procedural safeguards especially in the interception of communications by “National Security Organs” for the purposes of detecting or disrupting acts of terrorism.

Even though there is a provision for a warrant to be issued by a court of law, the broad definition of ‘national security’ leaves no room for restrictions on the extent of power the law grants to National Intelligence Service when it comes to accessing personal data, information and communications.

In February 2015, the Kenya High Court struck some clauses from the security law. The government says it may appeal.

Government says the new law is necessary to fight al Shabaab militants who have repeatedly rocked the country with fatal attacks such as the Westgate shopping centre attack on September 21, 2013, which left 67 people dead. Human rights activists blame President Kenyatta’s government for steadily shrinking the space for civil actors, a pattern they say was manifested in the Kenya Information and Communications (Amendment) Act 2013 and the Media Council Act 2013. These laws, they say, placed restrictions on media freedom and general freedom of expression.

The proposed Cybercrime and Computer related Crimes Bill (2014) also falls short of constitutional guarantees as it is contains “broad” speech offences with potentially chilling effects on free speech. See a full legal analysis of the Bill by Article 19. Proposed regulations to the law governing non-government organisations, which cap the funds received from foreigners at 15% of their overall budgets, have also been criticised as aimed to curtail and control the activities of civic groups engaged in governance and human rights work.

Over the 2012-2013 election period, several individuals were charged in court over their online communications. The National Cohesion and Integration Act of 2008 has been used to charge many for promoting hate speech – which some Kenyan citizens found justifiable given the role that hate speech played in the 2007 to 2008 post-election violence.

Hate Speech is defined by the 2008 Act as speech that is “threatening, abusive or insulting or involves the use of threatening, abusive or insulting words” with the intention to stir up ethnic hatred or a likelihood that ethnic hatred will be stirred up. Authorities, however, seem to be shifting gear and using this charge among others against online journalists and bloggers that criticise the Kenyatta government.

In December 2014, blogger Robert Alai was arrested and charged with undermining the authority of a public officer contrary to Section 132 of the Penal Code by allegedly calling President Kenyatta an “adolescent president” in a blog. He was again arrested in February 2015 for offending a businessman online by linking him to a land saga that involved the illegal acquisition of the Langata Primary School playground.

Meanwhile, Allan Wadi – a student – was also arrested for “hate speech” and jailed in January 2015 for posting negative comments on Facebook about the president. In the same month, journalist Abraham Mutai was arrested following tweets he posted on corruption in the Isiolo County Government. He was charged with the “misuse of a licensed communication platform to cause anxiety.”

Nancy Mbindalah, an intern with the department of finance at the Embu County Government, was charged on similar grounds for social media posts dating as far back as 2013 in which she is alleged to have abused County Governor Martin Wambora.

at the Embu County Government, was charged on similar grounds for social media posts dating as far back as 2013 in which she is alleged to have abused County Governor Martin Wambora.

In all instances, some social media users claimed there were “selective” arrests and prosecution of those critical of government. Critics cited the case of Moses Kuria, a Member of Parliament (MP) for Gatundu South, who allegedly made remarks on Facebook against the Luo Community but did not face the same punitive actions.

A recent news report, however, indicates that the National Cohesion and Reconciliation Commission and the Public Prosecutor are calling for the MP’s case to be revisited for the “incitement to violence, hate speech and fanning ethnic hatred.”

The incidents of arrest, prosecution and law amendments demonstrate a recurring theme of clamping down on dissenting citizen voices, a concern that was highlighted by the Kenya Human Rights Commission and the International Federation for Human Rights following the enactment of the Security Laws (Amendment) Act.

While the country remains on a constant alert for terror attacks, this has been used to strengthen the control that the state has on freedom of expression and surveillance. The lack of laws that limit state access to citizens’ information further exacerbates this concern.

ICT4Democracy in East Africa: Promoting Democracy and Human Rights Through ICTs

Established in 2011, ICT4Democracy in East Africa is a network of organisations working to promote democracy and human rights through Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania. Across the three countries, partners are leveraging on mobile short message service (SMS), toll free call centre, FM radio, social media, crowd sourcing platforms and direct community engagement to implement projects that tackle issues such as corruption, service delivery, respect for human rights, freedom of expression and access to information.

The projects are driven by the shared vision of the immense potential that ICTs have in increasing citizens’ participation in decision-making processes and strengthening democratisation.

The partner organisations are: the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA), Commission for Human Rights and Good Governance (CHRAGG), iHub Research, Kenya Human Rights Commission (KHRC), Toro Development Network, Transparency International Uganda and Women of Uganda Network (WOUGNET).

The network is supported by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) and the Swedish Program for ICT in Developing Regions (Spider). CIPESA is the network regional coordinator.

Read more about the network in the profile publication here.