By Lillian Nalwoga |

Encryption enables internet users to protect their data and communications from unauthorised access. Accordingly, anonymity and the use of encryption in digital communications are key enablers of citizens’ enjoyment of the right to privacy.

Worryingly, many African countries have passed legislation that limits anonymity and the use of encryption, purportedly to aid governments’ efforts to combat terrorism and crime. Other governments in the region limit the use of encryption to enable them to monitor the communications of critical journalists, human rights defenders, and opposition politicians.

In commemoration of the inaugural Global Encryption Day, the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) has published a policy brief that highlights restrictions to encryption and what needs to be done by governments in Africa to promote the use of encryption. The brief shows that encryption laws and government practices in several countries undermine the privacy rights of citizens, which in turn hampers their right to free expression and to secure use of digital technologies.

The importance of the right to anonymity in the digital era has been recognised in the Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information in Africa of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights. Principle 40(3) provides that: “States shall not adopt laws or other measures prohibiting or weakening encryption, including backdoors, key escrows, and data localisation requirements unless such measures are justifiable and compatible with international human rights law and standards.”

However, encryption is under threat from governments in Africa, as indeed in other parts of the world. Among the concerns cited by the brief are legislation and regulations that require registration and licensing of encryption service providers before they can offer cryptographic services. This is the case in Benin, Chad, Cameroon, Congo Brazzaville, Democratic Republic of Congo (DR Congo), Ethiopia, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Malawi, Mali, Morocco, Senegal, South Africa, Tanzania, Tunisia and Zambia, among others. Offering encryption services without a license attracts penalties, as does failure to hand over secret encryption codes to state authorities, or using prohibited encryption tools.

The requirement for registration of encryption services providers makes it easy for regulators and other government agencies to access information held by these service providers, including decryption keys and encrypted data. This undermines best practices which require governments to reject laws, policies, and practices that limit access to or undermine encryption and other secure communications tools and technologies.

Further, the brief points to how governments in Africa prohibit the use of some types of encryption and require disclosure to regulators of the characteristics of cryptology. Crucially, governments should not prohibit the use of encryption by grade or type. Further, governments should not mandate insecure encryption algorithms, standards, tools, or technologies.

Meanwhile, laws on interception of communications across the continent including in Benin, Cameroon, Chad, Ivory Coast, Malawi, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania, Togo, Tunisia, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe require communication service providers to put in place mechanisms, including the installation of software, which facilitates access and interception of communications by state agencies. Indeed, state agencies in several countries can request for decryption of data held by service providers, which poses a big concern.

For instance, Zimbabwe’s Interception of Communications Act requires cryptography services providers to decrypt data at judicial authorities’ request or provide them with the codes allowing the decryption of data they have encrypted (article 78). Section 11(1)(d) permits security agents to demand that information is decrypted before it is handed to them, where the disclosure is necessary for national security, to prevent or detect a severe criminal offense, or in the interests of the country’s economic well being. Failure to comply is punishable with up to five years’ imprisonment, a fine not exceeding USD 373, or both. Similar provisions are found in the laws of several other countries.

Such compelled assistance from service providers has been reinforced with mandatory SIM card registration of phone users around the continent, as well as data localisation requirements amidst ineffective safeguards.

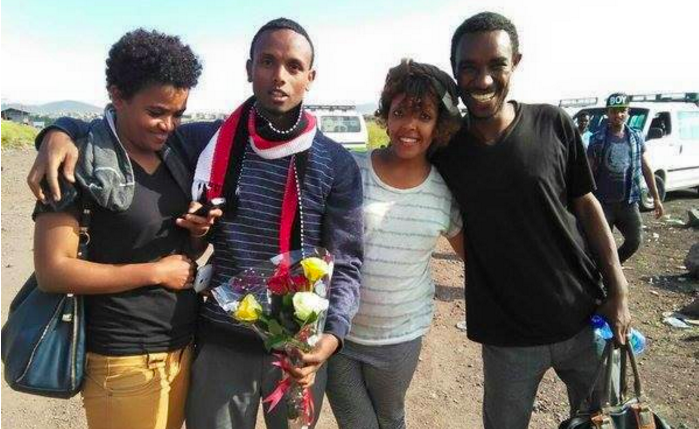

In some countries, if the private communications of human rights defenders and opposition politicians fall into the hands of state agencies, the consequences can be dire. The brief cites Rwanda, where the private communications of musician Kizito Mihigo, opposition leader Diane Rwigara, and two former army officers were used in their separate prosecutions. In Ethiopia, the Zone 9 bloggers were detained and prosecuted, among others, for using encrypted communications.

Meanwhile, Uganda instituted a ban on use of Virtual Partial Networks (VPNs) in the face of internet taxes and network disruptions. For its part, Zimbabwe barred telecom operator Econet Wireless from introducing the Blackberry Messenger service, which provided encrypted messaging, arguing that it contravened the southern African country’s interception of communications law which bars provision of services which the communications regulator can not intercept. Another example cited is Mauritius, which this year attempted to introduce a controversial lawful interception mechanism that would decrypt and re-encrypt all social media traffic.

In light of the above concerns, the CIPESA brief is urging governments to repeal or amend provisions that place undue restrictions on the use of encryption tools; cease blanket compelled service providers and intermediary assistance to state agents and instead provide for clear and activity-bound assistance; and enact data protection and privacy laws that robustly promote the use of strong encryption.

The full brief can be accessed here.