By Ainembabazi Patricia |

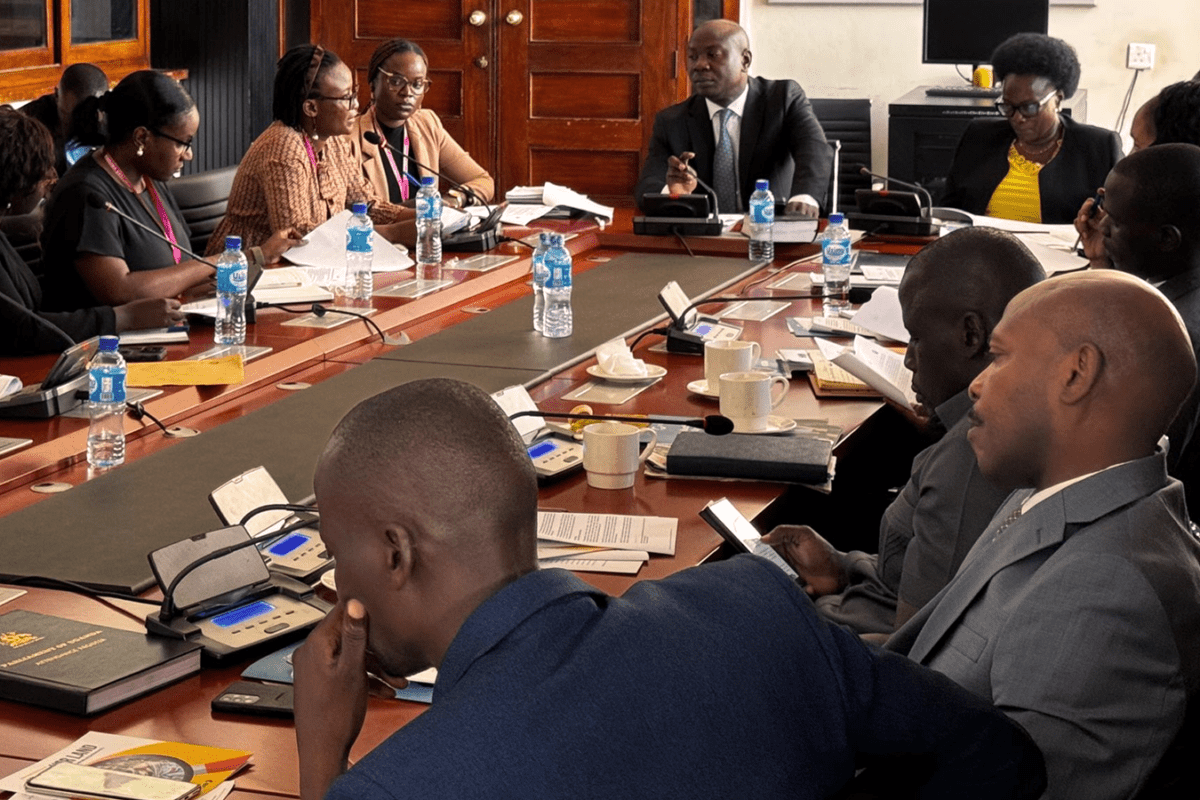

On February 18, 2025, the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) alongside Pollicy and the Gender Tech Initiative appeared before Members of Uganda’s Parliament to advocate for the inclusion of Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence (TFGBV) in the Sexual Offences Bill 2024.

The rapid evolution of digital technologies has reshaped societal interactions, leading to increased perpetration of online violence. In Uganda, online users increasingly face digital forms of abuse that often mirror or escalate offline sexual offences, yet efforts to combat gender-based violence are met with both legal and practical challenges.

The Sexual Offences Bill aims to address sexual offences by providing for the effectual prevention of sexual violence, enhancement of the punishment of sexual offenders, providing for the protection of victims during trial of sexual offences, and providing for extra-territorial application of the law.

In the presentation to Committee of Legal and Parliamentary Affairs and the Committee on Gender, Labour, and Social Development, CIPESA and partners emphasised the necessity of closing the policy gap between digital and physical sexual offenses in the Bill, to ensure that Uganda’s legal system is responsive to the realities of technology advancements and related violence. We argued that while the Bill is timely and presents real issues of sexual violence especially against women, there are some pertinent aspects that have been left out and should be included.

According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), TFGBV is “an act of violence perpetrated by one or more individuals that is committed, assisted, aggravated, and amplified in part or fully by the use of information and communication technologies or digital media, against a person on the basis of their gender.” It includes cyberstalking, doxing, non-consensual sharing of intimate images, cyberbullying, and other forms of online harassment.

In Uganda, TFGBV is not addressed by the existing laws including the Penal Code Act and the Computer Misuse Act. Adding TFGBV to the bill will provide an opportunity to bridge this legal gap by explicitly incorporating TFGBV as a prosecutable offence.

CIPESA and partners’ recommendations to the Committees were to:

1. Include and Explicitly Define TFGBV

Under Part I (Preliminary), the Bill provides definitions for various terms related to sexual offences, including references to digital and online platforms. However, it does not explicitly define TFGBV or recognise its various manifestations. This omission limits the Bill’s effectiveness in addressing emerging forms of online sexual offences.

We propose an introduction of a new clause under Part I defining TFGBV, to ensure the Bill adequately addresses offences committed via digital means. The definition should align with international standards, such as the UNFPA’s definition of TFGBV, and should ensure consistency with Uganda’s digital policy frameworks, including the Constitution of the Republic of Uganda 1995, the Data Protection and Privacy Act, 2019, the Computer Misuse (Amendment) Act 2022, Penal Code Act Cap 120, and the Uganda Communications Act 2013.

2. Recognising Various Forms of TFGBV

Clause 7 of the Bill provides for the penalisation of Indecent Communication or transmission of sexual content without consent. It criminalises the sharing of unsolicited material of a sexual nature, including the unauthorised distribution of nude images or videos. However, the provision does not explicitly mention cyber harassment, online grooming, sextortion, or non-consensual intimate image sharing (commonly known as “revenge porn”). As such, we recommended the expansion of Clause 7 to explicitly recognise and define offences such as Cyber harassment, Non-consensual intimate image sharing, Online grooming, and Sextortion. This addition will clarify legal pathways for victims and broaden the scope of protection against digital sexual exploitation.

3. Replacing “Online Platform” with “Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence”

In clause 1 the Bill defines “on-line platform” as any computer-based technology that facilitates the sharing of information, ideas, or other forms of expression. This encompasses social media sites, websites, and other digital communication tools. Clause 6 addresses the offense of indecent exposure, criminalising the intentional display of one’s sexual organs in public or through electronic means, including online platforms and clause 7 pertains to the non-consensual sharing of intimate content. However, these provisions do not comprehensively categorise TFGBV as a distinct form of sexual offences. Accordingly, “Online Platform” should be replaced with “Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence” to ensure the Bill adequately captures all digital gender-based offences, including deepfake pornography, cyberstalking, and sexual exploitation through content generated by artificial intelligence.

4. Criminalising Voyeurism

The Bill does not explicitly criminalise voyeurism, which refers to the act of secretly observing, recording, or distributing images or videos of individuals in private settings without their consent, often for sexual gratification. Thee is increasing prevalence of voyeurism through hidden cameras, non-consensual recordings, and live-streamed sexual abuse. Voyeurism should be criminalised with a clear definition provided under clause 1 and the scope and penalty defined under Part II of the Bill.

5. Strengthening Accountability for Technology Platforms

The Bill does not impose specific responsibilities on digital platforms and service providers in cases of TFGBV. We argued for the addition of a new clause under Part III (Procedures and Evidential Provisions) mandating digital platforms and service providers to cooperate in investigations related to TFGBV, and provide relevant data and evidence upon request by law enforcement. Similarly, the provision should expand into the obligation to ensure data protection compliance and implementation of proactive measures to detect, remove, and report sexual exploitation content. This provision will enhance accountability and facilitate the prosecution of perpetrators.

6. Aligning Uganda’s Legislation with Regional and International Frameworks

The Bill does not explicitly state its alignment with regional and international human rights instruments addressing sexual violence and digital rights. We recommend an addition of a new clause under Part I (Preliminaries) stating that the Bill shall be interpreted in a manner that aligns with the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) Resolution 522 (2022) and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). This will reinforce Uganda’s commitment to and application of international best practices in combating sexual offences.

7. Enhancing Legal Remedies for Survivors

Clause 42 (Settlement in Capital Sexual Offences) prohibits compromise settlements in cases of rape, aggravated rape, and defilement, prescribing a 10-year prison sentence for offenders who attempt to settle such cases outside court. However, the Bill does not provide civil remedies for victims of TFGBV-related crimes, nor does it ensure access to psycho-social support. We recommend an expansion of Clause 42 to include civil remedies, including compensation for victims of TFGBV, psychosocial and legal support, ensuring survivors receive necessary rehabilitation, and mandatory reporting obligations for online platforms hosting TFGBV-related content.

The inclusion of TFGBV in the Sexual Offences Bill 2024 will not only strengthen the fight against gender-based violence but also ensure that survivors access justice. The proposed legislative changes will reinforce Uganda’s commitment to upholding digital rights and gender equality in the digital age. The country will also join the ranks of pioneers such as South Africa who have taken legislative steps to criminalise online gender-based violence.

By incorporating the proposed provisions and amendments, the Sexual Offences Bill, 2024 will clearly define online-based sexual offenses, bring perpetrators of online violence to book and provide protection for survivors of digital sexual offences. It will also contribute to the building and strengthening of accountability for technology platforms. Once enacted, the law will also go strides in ensuring that Uganda’s legal framework aligns with regional and international human rights standards on protection of survivors while guaranteeing effective prosecution of offenders of technology-facilitated sexual offences.

Download the Full report here