Tweet

By Ashnah Kalemera |

In pursuit of strategic mechanisms to promote and protect human rights in Tanzania, the Commission for Human Rights and Good Governance (CHRAGG) has this year embraced the use of digital technologies to advance the right to health among vulnerable communities and human rights practitioners in five regions in Tanzania.

In August 2016, CHRAGG embarked on a campaign that leverages its SMS for Human Rights reporting system to improve rights awareness and protection for some hitherto marginalised groups. Under the drive, up to 100 commission staff at the head office in Dar es Salaam and three regional offices (Mwanza, Lindi and Zanzibar) have been trained to improve their understating of the right to health and to enable them to appropriately handle related violation reports received through the digital platform.

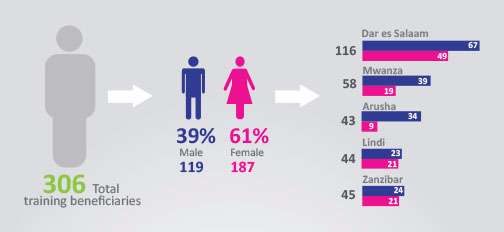

The CHRAGG training also benefited 190 individuals including sex workers, the elderly, women, health practitioners and local leaders who were trained on the principles of the right to health and how to monitor and report rights violations. Most of the training beneficiaries (61%) were female.

Breakdown of training beneficiaries

By Gender

By category

Vulnerable and marginalised communities such as indigenous people, women, and sexual minorities are often less likely to enjoy the right to health. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), achieving all citizens’ right to health is closely related to other human rights including non-discrimination, access to information and participation.

The right to health includes both freedoms and entitlements.

Freedoms include the right to control one’s health and body (e.g. sexual and reproductive rights) and to be free from interference (e.g. free from torture and from non-consensual medical treatment and experimentation).

Entitlements include the right to a system of health protection that gives everyone an equal opportunity to enjoy the highest attainable level of health.

See WHO Health and Human Rights Factsheet

As a result of the training, CHRAGG staff have better understanding of minority rights and have incorporated this knowledge into their daily work. As stated by one staff member, the training enabled them to make the link between the right to health, free expression and equality. “I never thought [other rights] are covered in right to health,” he said. Another noted, “I did not know [that] the commission could be involved in this,” referring to protection of the right to health.

However, training participants highlighted concerns in using the system such as slow resolution of reports. Going forward, commission staff are expected to specifically categorise health rights violation reports received from minority and vulnerable groups as part of case handling procedures and work towards their speedy resolution.

In December 2012, CHRAGG launched the SMS for Human Rights System to make it easier for citizens to report human rights violations. Since then, the commission has conducted campaigns throughout Tanzania to raise awareness about the system. This has greatly boosted the number of reports received through SMS.

The commission is developing and testing a minority groups’ database within the existing complaints handling system. Once implemented, the database will enable toll-free human rights violations reporting for minorities, efficient and confidential case management and follow-up, as well as disaggregation of statistics on minority rights abuses

Established in 2001 in fulfillment of Tanzania’s national constitution, CHRAGG plays the dual role of an ombudsman and a human rights commission for the protection and promotion of human rights and good governance.

CHRAGG is a member of the ICT4Democracy in East Africa Network whose work is supported by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) and the Swedish Programme for ICT in Developing Regions (Spider). The network is coordinated by the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA).

coming those challenges. Panelists included the Kenya National Commission

coming those challenges. Panelists included the Kenya National Commission